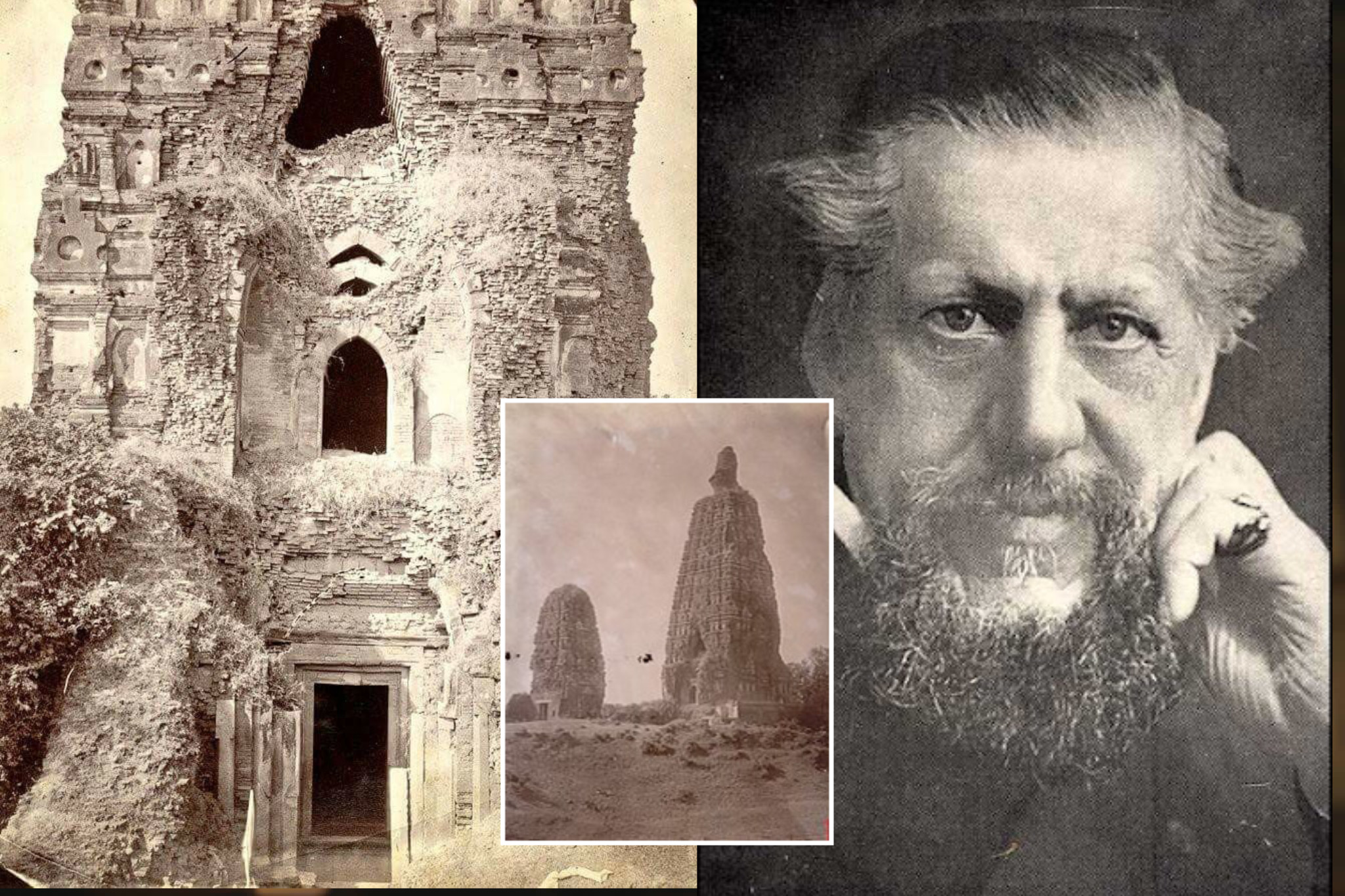

Colombo, August 26: Sir Edwin Arnold, a 19 th., Century Indologist, journalist, poet andauthor of the immensely popular Light of Asiaon the life of the Buddha, campaigned hard, both singly and in collaboration with the Ceylonese monk Anagarika Dharmapala, to retrieve the ancient Buddhist shrine at Buddha Gaya from the hands of a Saivite Hindu priest, called the Mahant.

Arnold’s role in the struggle for retrieval is vividly brought out by Jairam Ramesh in his book: The Light of Asia: the poem that defined The Buddha (Penguin Random House, India,2021).

Arnold told the then British rulers that the Bodhi tree at Buddha Gaya, under which the Buddha got Enlightenment, is as holy for the Buddhists of the world as Jerusalem is for Christians and Mecca is for Muslims. Arnold passionately advocated that the temple ought to be handed over to the Buddhists of the world. He kept dinning into the ears of the British rulers that its handing over to the Buddhists will immeasurably enhance the image of the British in the Buddhist countries of Asia including China and Japan.

But sadly, Arnold and Dharmapala did not fully succeed in their mission in their life time. The British were wary about divesting the Mahant of his hold over the temple, for fear of a Hindu backlash, especially because it had acquired Hindu deities like Siva also. It was not until after India’s independence that the Mahant was gradually divested of his powers. Power over Buddha Gaya now rests with a committee comprising officers of the Bihar State government, Hindus, and Buddhists from India and abroad. It is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

When Arnold visited Buddha Gaya for the first time in 1886, he was appalled to see hundreds of valuable artefacts, priceless works of art, piled on each other haphazardly. He wrote to Sir William Wilson, member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council, suggesting that the artefacts be cleaned and kept in a safe place. It is not clear if Sir William responded, but Arnold went to Ceylon and met the famous monk WeligamaSri Sumangala at Pandura who “expressed an ardent wish that the Buddhists might someday recover the guardianship of that sacred ground in Buddha Gaya.” The monk added: “It ought not to be in any hands except those of Buddhists.”

In November 1886, Arnold wrote to Sir Arthur Gordon, Governor of Ceylon, saying that the guardianship of the shrine should be given to the Buddhist monks of Ceylon. Gordon was told that Buddha Gaya was the “geographical center of Buddhism” and that it would attract Buddhists from Tibet, Siam, Burma, China and Japan. Arnold followed this up with a letter to retired archeologist Sir Alexander Cunninghammooting a Government of India Act to acquire the temple as the land on which it stood was government’s. The Brahmin priests could be paid off, Arnold added.

Enter Anagarika Dharmapala

Five years later, the Ceylonese monk AnagarikaDharmapala joined Arnold’s campaign. He had read Arnond’s India Revisited in 1886, in which the sad state of Buddha Gaya was mentioned. When Dharmapala went to Buddha Gaya with a Japanese priest, Kozen Gunaratna, he found that the Mahant was treating the Buddhists “with utter contempt.” In 1891, Dharmapala founded the Mahabodhi Society in Colombo with Weligama Sri Sumangala as President and an international managing committee including Arnold. But since the Government of India was crucial for the retrieval project, he shifted the Mahabodhi Society to Calcutta which was then the capital of India.

Back in Britain, Arnold badgered the Secretary of State for India, Lord Kimberley, with letters on the issue. In an 1893 missive, he told Kimberley: “Your Lordship might cover your Administration with glory and gratitude, by half a word to the Bengal authorities.” Bodh Gaya was then under Bengal. Kimberley said that the Bengal authorities would not interfere in the matter but suggested that Arnold get someone to buy the property and that the “authorities would assist the purchasers in making the necessary arrangements for the transfer.”

Earlier, Arnold had written to Lord Cross, Secretary of State for India, who had taken up the matter with Lord Lansdowne, the Viceroy of India. Lansdowne had replied that the government had no objection so long as the issue did not whip up any “religious feeling” and if there was no demand for a “pecuniary grant from the treasury.”

In July 1893, Dharmapala was in London enroute to Chicago to attend the World Parliament of Religions. He called on Lord Kimberley along with Arnold. Kimberley toed the now familiar British line that the government did not want anything “dramatic” which would antagonize Hindu sentiment. However, he had sounded out Lord Lansdowne in Calcutta who had said that transfer of the property was not advisable when “agitations of a religious character possess peoples’ minds in Bihar.” Lansdowne also stated that Buddha Gaya was treated with reverence by the Hindus also.

Arnold acquiesced in this and decided to wait for a more propitious time to revive themovement. But Dharmapala took a couple of precipitate steps unilaterally. In February 1895 he surreptitiously installed a 700 year old statue of a Japanese–sculpted Buddha within the temple. When violence ensued, he shifted it to the Burmese pilgrim’s rest house and filed a case in a Magistrate’s court for legal ownership. Ven.Sumangala Thera and Col.Olcott were against this move as they knew that while the Buddhists’ right to worship was “unimpeachable” their legal right of ownership was “ambiguous.” They preferred a negotiated solution.

Sure enough, Magistrate D.J.Macpherson ruled that Dharmapala or the Mahabodhi Society had no right to represent the interest of the Buddhists and that they were being led by non-Buddhists Arnold and Olcott. However, Macpherson also said that the Mahant and the government held “dual custodianship” over the temple.

This troubled Mahant went on appeal to the Sessions Court. The Sessions Court said that though the priest’s proprietary rights over the temple and its surroundings found expression in the government’s own list of Ancient Monuments issued in 1886, it did not constitute a “deed or grant.” The priest then appealed to the Calcutta High Court where a two-judge bench gave a divided verdict.

The British judge said that “if the temple was not vested in the Mahant, it was not vested in any one.” But the Indian judge said that on the basis of the evidence adduced “it is difficult to define the exact nature and extent of the Mahant’s control over the temple.” In 1895, Arnold wanted to come back to India to negotiate with the Mahant and wrote a letter to the latter in Hindi informing him about the plan. But the trip did not materialize.

In 1896, the British tried to defuse the tension over the Buddha Gaya temple and removed the Japanese-gifted Buddha statue from the Burmese Rest House to the Indian Museum in Calcutta. Dharmapala protested vehemently. Many of the Indian leading lights in Calcutta supported him. The Indian English language media also wrote in support of him. Indian support proved to be effective. In May 1896, the government reinstated the Buddha statue in the Burmese Rest House.

Exulting in this, Dharmapala wrote to Arnold declaring “the cause of Truth has triumphed at last, and Buddha Gaya has been restored to the Buddhists after seven centuries of oblivion.” Thanking Arnold, he said: “The work initiated by you in 1886 has been successfully realized in 1896.”

However, the rich and never-say-die Mahant,pursued his case through the British Indian Association. But the Chief Secretary of Bengal told the association that the government is unable to accept that the temple is a Hindu one.However, no action was taken to give it to the Buddhists. What followed was a long, politically sustained stalemate, which ended only after India got independence.

END