By Vishvanath

Yummy lemon cream biscuits and attractive election manifestos are like chalk and cheese, but they have one thing in common—lack of genuineness. The former are marketed with false claims to mislead the public, and the latter contain mistruths intended to dupe voters. What prompted this column was an instance of successful PIL (Public Interest Litigation) against a local biscuit manufacturer.

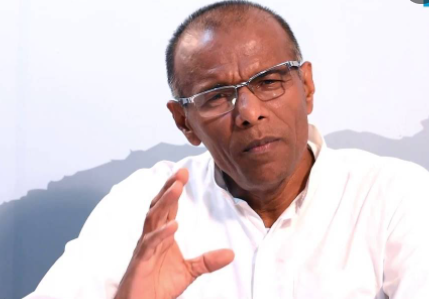

PIL lawyer and General Secretary of Lanka VinividaPeramuna, Nagananda Kodituwakku, is in the news, again—for the right reasons. He has successfully invoked the jurisdiction of the Court Appeal against the aforesaid biscuit company, which, as a result, had to discontinue the use of a false claim that its biscuits contained ‘real lemon cream’. Kodituwakku took the trouble of informing the court that the company had beenmisleading the public in violation of the food standards regulations, as reported by Counterpoint, the other day. The writ application was withdrawn after the company concerned discarded the wrappers with the false claim printed on them.

Many are the companies that make such false claims to sell their products and services. Some milk powder manufacturers dupe the public into believing that their products enhance children’s mathematical skills immensely. Some artificial beverages are made out to be better than even natural fruit juices. The cosmetics market is awash with creams touted as being capable of making dark skins fair overnight. Hyperbole as well as deceit is synonymous with advertising, but the foregoing successful writ application has demonstrated that the sky is not the limit, and manufacturers who make bogus claims run the risk of being hauled up before courts. This country needs many morepublic-spirited lawyers like Kodituwakku to defend the rights of the public.

Kodituwakku’s mission

Kodituwakku’s long suit, however, is not ensuring accountability on the part of private companies. His mission is to cleanse Sri Lankan politics, hold politicians accountable for their actions, and fight corruption. Now that he has scored an impressive win against a powerful local biscuit manufacturer, he should concentrate on taking action against the false claims that politicians and political parties publicize to dupe the public into voting for them.

Unfortunately, no legal options are available for political parties to be held accountable for the election manifestos which contain various promises that are, like the pie crust, made to be broken. Nobody cares whether these pledges are fulfilled or not, and the unfulfilled ones only end up as grist for the Opposition’s mill.

The fact that not many people take election manifestos seriously, and hardly anyone expects them to be implemented is no reason why they should not be made legally binding. There are many other things that the ordinary public take for granted but are legal binding, conditions in small print on loan applications being a case in point. If it is illegal for a company to sell a product by deceiving the public, the act of securing power to govern a country by duping the public must be a far more serious offence.

Promises and manifestos

The need for political parties and politicians to be held accountable for their manifestos and pre-election promises has been felt the world over, especially in the developing worldwhere polls pledges could be outlandish. The following were the key promises in the AIADMK election manifesto put out by the then Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Jayaram Jayalalithaa ahead of the 2016 assembly polls, according to India Today:

1. Free cell phones for all ration card holders in the state.

2. Free Laptops for students.

3. Free gold for women ahead of marriages.

4. Free ride: Women to get 50 per cent subsidy to buy scooters.

5. Free housing: The manifesto has promised one millionhouses through various housing schemes.

6. Cheaper milk: Aavin, the state dairy federation, will provide milk for just Rs 25 per litre.

7. Amma Banking Card: New banking card to avail government services.

8. Free power: Amma will provide 100 units of electricity free every two months.

9. Loan waiver: AIADMK promises waiver of all farm loans.

10. Maternity assistance: If it returns to power, the AIADMK government would provide Rs 18,000 as maternity assistance to expecting women.

In this country, too, there have been many such promises which range from measures of rice to lofty ideals such as good governance. In 1970, Sirima Bandaranaike promised two measures of rice per household and undertook to deliver on her pledge even if rice had to be brought from the moon. In 1977, J. R. Jayewardene promised eight pounds of grains and a righteous society. In 1988, Ranasinghe Premadasa’s promise was to provide every family with a house while eradicating poverty. In 1994, Chandrika Kumaratunga pledged to rid the country of terror and corruption, and make bread available at Rs. 3.50 a loaf. In 2005, Mahinda Rajapaksa said he would ensure a bright future for everyone. In 2015, Maithripala Sirisena offered to usher in good governance. Ranil Wickremesinghe, who sought a mandate at the 2015 parliamentary polls promised tablet PCs to all students and free Wi-Fi to the youth. Gotabaya Rajapaksa, secured the executive presidency, in 2019, by promising to bring about prosperity. If these promises had been carried out, Sri Lanka would have been a utopia.

Unsuccessful attempts

There have been some efforts to make election manifestos legally enforceable. Unfulfilled promises in election manifestos have caused concern to the public even in advanced democracies such as Britain. In 2019, a group of British voters initiated a petition to the British parliament, seeking to have election manifestos made legally binding. The introduction to the petition read: “Election manifestos are seen by the public as a promise. However, they are frequently misleading or downright lies, and, therefore, enact a law to ensure that they are classified as advertising (or similar) so they are subject to legal enforcement against each political party to restore trust in politics.” But the petition was closed early as the election was held, and nothing came of it.

In 2015, Mithilesh Kumar Pandey, an Indian lawyer, filed a PIL in the Indian Supreme Court (SC), requesting that the political parties be ordered to fulfil their pre-election promises or stay away from post-polls alliances. His argument was that the court was constitutionally empowered to lay down guidelines to stop political parties from making false and illegal promises. But the court was convinced otherwise. In May 2016, the SC said the judiciary was not there to provide a cure for every problem in the political system, and dismissed the petition.

In 2014, the Election Commission of India (ECI) drafted the Model Code of Conduct, containing guidelines prohibiting political parties from making pledges in their manifestos exerting undue influence on votes. However, this code is not legally enforceable and the ECI can only censure political parties that do not follow it. In 2016, it rebuked the AIADMK for failure to explain how it was going to raise funds for the fulfilment of the promises in its election manifesto put out for the Tamil Nadu assembly polls. But censuring alone does not ensure compliance. There have to be laws, which must be strictly enforced.

Way forward

Sri Lankan politicians are a very ‘promising’ lot; they make a lot of promises and fulfil hardly any after being elected, as was said earlier. If democracy is to be the social contract that it is said to be between electors and the elected, solemn pledges those who seek power make in their manifestos have to be honoured; their failure to do so amounts to a breach of trust, which severely erodes public faith in the electoral process, the lifeblood of representative democracy. Hence the need to hold political parties and their leaders accountable for what they obtain popular mandates for. This matter should not be taken lightly in that the elected have control over not only the public purse but also every aspect of the polity and even the destiny of a nation.

People ask for warranties even when they purchase cheapelectronic gadgets, take great pains to ensure that they get the real McCoy, and fight when the warranty conditions are not fulfilled, but they do not exercise such caution when they elect governments.

There have been some half-hearted attempts to have laws made to hold political parties accountable for their election manifestos in this country as well. But the time has come for a serious attempt to be made to achieve that goal, given the rapid erosion of public faith in the electoral process and political parties. It is up to the various civil society groups, the media and other stakeholders to join forces with Kodituwakku, who has been fighting a lonely battle against social evils to achieve the goal of cleansing politics and enforcing accountability lest democracy should lose its vigour and vitality further.