By N Sathiya Moorthy

26 March 2024

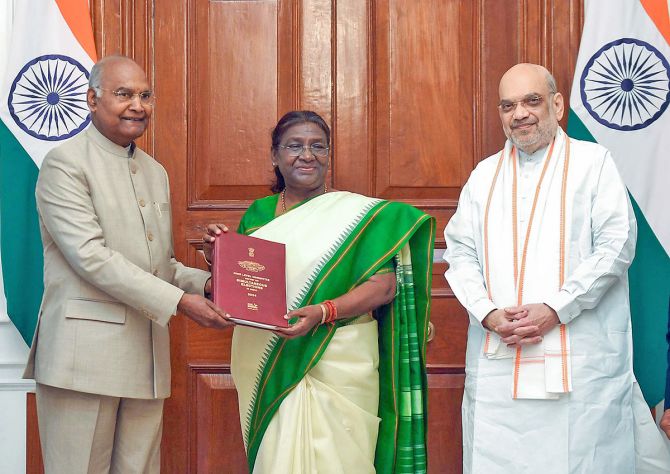

Congress President Mallikarjun Kharge may have over-shot the target when he said the electoral scheme proposed by the Ramnath Kovind Committee, headed by former President Ram Nath Kovind meant ‘one-nation-no-election’ instead.

Patently deriving from Narendra Modi’s continuing charisma, the proposed scheme, if and when implemented, can cut both ways.

That is to say, if Modi can win, he can lose. Or, someone else in his place, later on, could lose as much as he could win in his time.

Alternatively, he or she could also lose what all Modi has gained for the party, all across.

Yes, all-across is the phrase that is the spirit of the Kovind report, which seems to have adopted one-party-one-leader governance, bottom-up, from the panchayat-level to Parliament and prime minister, through state legislatures.

All of it will be done in the name of democracy that too, the existing scheme of multi-party democracy.

Given that ‘ideology, whatever it be and whether you like it or not, is at the core of the social reach, political existence and even the scheme of governance all across for the ruling party, the Kovind Report, if implemented, say, may help the Sangh Parivar to institutionalise their ideology-orientation through a systematic intrusion, which anyway they do not need just now.

If the BJP clears the required numbers — say, the 400-seat target for the party-led NDA, as Modi has been playing a poll-eve psy-war on the nation’s voters — then, the Kovind scheme could become what the abolition of Article 370 was at the end of elections 2019 — fast and furious before the nation could even recover from poll fatigue to grasp the nuances of it all!

The reasons are not far to seek. Across most states in the country, the BJP has been in charge of elected bodies, again from panchayats upwards.

What they seem needing urgently at present is two or three terms of five years at a stretch to create an ‘Opposition-mukt‘ nation all across, not stopping with a ‘Congress mukt‘ Bharat or a ‘DMK mukt’ Tamil Nadu.

It is the BJP’s conviction that the Congress has been destroyed beyond redemption to its past existence and the realisation that they could make it an one-party State without saying it, but doing it only if they also destroyed all regional parties. The list is long, and their grassroots-level reach is also deep.

From Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress to Akhilesh Yadav’s Sanajwadi Party to Tejashwi Yadav’s Rashtriya Janata Dal to the Shiv Senas and Akali Dals, not to leave out allies like the Janata Dal-United and the Janata Dal-Secular, the Telugu Desam Party and the Jana Sena, there is an impressive list, still.

This is not to forget the ruling Dravida Munnetra Kazagham and the rival All India Dravida Munnetra Kazagham in Tamil Nadu, and the eternal cat-on-the-wall in Odisha’s Biju Janata Dal and Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party in UP.

However weak they may have become over the past decade of the Modi regime — and more so, the ‘Modi magic’ to be precise — it still takes time to root them all out, just out of recognition and even basic existence.

You still may not say so, but if that happens, a one-party government, if not one-party State, as in China or elsewhere, would have been achieved without changing the much-hyped ‘basic atructure’ and character of the nation’s Constitution, one way or the other.

What if the basic premise of the BJP does not work, if not now, but on a later day? And what is this basic premise?

It is built on the strongest of beliefs and convictions that Modi is the most charismatic leader in the country with no one, inside the party and more so outside coming anywhere close to him — and thus his natural ability to attract voters and their votes in volumes that the party or the nation had not seen, at least since the turn of the century.

The idea, as indicated by the Kovind report, is for the BJP to sweep all elections across the board in one great sweep.

If so, it could commence with the next round of Lok Sabha polls, due in 2029.

By then, much-delayed new Census figures and delimitation of Lok Sabha and state assembly constituencies too would have been completed, as per current schedule.

There is already talk of increasing the number of Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha seats.

It was said to be among the reasons for the hurried construction of a new Parliament complex, which is already in full use.

Of course, there is the huge possibility of ‘developed States’ across south and west India, losing the existing number of Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha seats, owing to their successful implementation of family planning schemes over the past decades.

The question is how effective would be their protests and protestations, both inside and outside the Supreme Court, as they would have lost their voice(s) inside Parliament even if they monopolised regional politics, on this one issue.

The BJP, to be fair to the party, might have been encouraged by the electoral successes in Karnataka, which is also a fast-developing state, like Tamil Nadu, Telangana and Maharashtra.

It would still be interesting to note if Modi’s native state of Gujarat, which is among the most developed states, would lose parliamentary seats, post-delimitation.

Rather, the question translates into one on the success of family planning in the state, thus leading to lower population growth-rate, as in the ‘developed and enlightened’ South.

Present projections show a falling population growth rate, however.

That said, there is still nothing to suggest that Modi could become as unpopular as he is now popular. But a future leader or a series of leaders who may end up stepping into his shoes over time need not be as popular as he is at present. The possibilities are immense and can cut both ways.

The BJP-RSS strategists, whether sitting in Nagpur or working their computers as NRI ideologues overseas, on all kinds of projections, may suffer from the same kind of self-indulgence that their one-time Communist rivals got accustomed to.

Their kind of ‘see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’ approach led to a situation in which the Communists won’t listen to what the world, from grassroots upwards, had to tell them on how outdated their policies and mass programmes were.

Today, the multiple Communist parties in the country are worse than in their death-beds.

Barring Kerala, where the world’s first democratically-elected government happened in 1957, there is no Communist party worth the name elsewhere.

That includes West Bengal and Tripura, where they had controlled elected governments for decades without end — but not any more, now or later.

All told, the BJP’s current exercise is only a take-off from their earlier attempt at trying out the presidential form of government, where they thought the greater popularity of then prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee would help sweep the nation.

That itself was only an adaptation from a similar provision in the anonymous draft of the ’42nd Constitution Amendment’ that was doing selective rounds during the Emergency.

However, a second draft, whose parentage too no one claimed, had dropped this provision — as it did not reportedly find favour even within then prime minister Indira Gandhi’s inner circle.

Though not anticipated, the complete rout of the Congress party in the post-Emergency parliamentary polls of 1977 — when Indira Gandhi too lost her Raedd Bareli seat by a 55,000 vote margin.

Incidentally, it was the complete rout of the Congress in the Hindi belt that reportedly gave the Vajpayee-L K Advani duo the idea that with a charismatic leader sweeping the Hindi belt, they could win a presidential election more comfortably than a parliamentary polls, which was a more elaborate affair.

The reversals that the BJP suffered in assembly elections in some north Indian states convinced the party enough that the Vajpayee Centre tasked the Justice Venkatachellaiah Commission to ‘review the working of the Constitution’ in general terms, without considering the presidential form.

Today, the one-nation-one-vote proposition too aims at betting on Modi’s greater popularity and inherent charisma, but in more systematic bottom-up approach, where the party hopes to capitalise on the same even at the panchayat level.

Given two, or even one set of elections under given circumstances, the BJP would have perpetuated what would then tantamount to one-party rule across the board.

Only that as long as electoral democracy prevails in the same form as it exists now, there is always the flips side, as happened to Indira Gandhi, post-Emergency (1977) Rajiv Gandhi, post-Bofors (1989) and also Vajpayee in elections 2004, where the BJP’s ‘India Shining’ campaign proved to be a dud.

Thus, Mallikarjun Kharge’s prediction of ‘one-nation-no-election’ may not happen, as the perpetrators seem wanting Constitutional legitimacy, without which they could end up crossing swords with the higher judiciary.

Such a course will be bad publicity, which the leadership does not desire more outside the country under the given circumstances than even inside.

Of course, it has nothing to do with the likes of the Supreme Court’s verdict in the Electoral Bonds case.

Maybe, the government had thought that by side-stepping the Supreme Court’s direction to include the Chief Justice of India in the three-member panel to select election commissioners would give them absolute authority over the nation’s poll process — which is the world’s largest democratic drama in action.

But the government seems to have forgotten how Indira Gandhi’s dispensation that won the historic 1971 War lost the immediate next general elections, post-Emergency, 1977, on issues that the leadership had not anticipated — and hence caught unawares.

If nothing else, for the ruling Congress of the time, Indira Gandhi’s popularity in 1971 became a burden in 1977 — and cut both ways, after all!