By Vishvanath

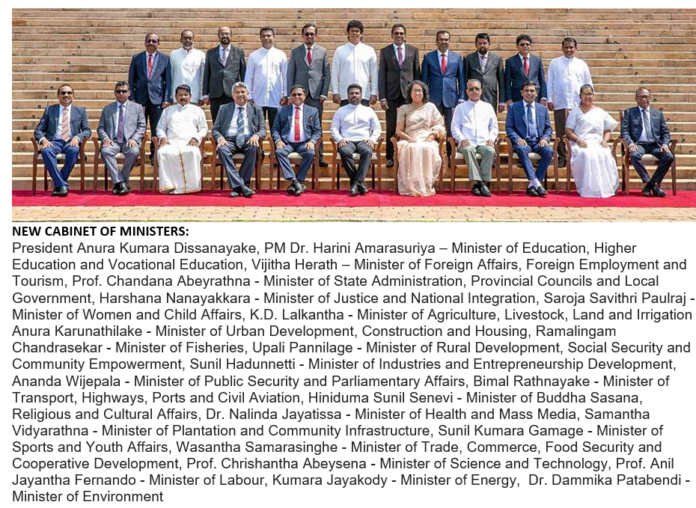

A 21-member new Cabinet has been appointed, and the JVP-led NPP is now about to learn what it is like to wield unbridled power, which it had been dreaming of for decades.

The people have given President Anura Kumara Dissanayake and the NPP much more than they asked for ahead of the recent general election—an unprecedented majority (159 seats in the 225-member House). President Dissanayake, addressing the newly-appointed ministers on Monday (18), at the Presidential Secretariat, said his government was mindful of its responsibilities, and never would the huge majority be abused in any manner. His pledge was reassuring, but the proof of the puddling is said to be in the eating.

Sri Lanka’s experience with huge majorities for governments has been extremely bitter. They make rulers cocky, complacent, aggressive and blind to reality. This, we saw in 1970, 1977, 2010 and 2019/2020; the winners either introduced new Constitutions or amended the existing ones to suit their own interests at the expense of the country’s democratic wellbeing. Whether the NPP will be different remains to be seen.

Last week’s spectacular victory was a dream come true for the JVP, which struggled for nearly four and a half decades to realize it by violent means on two occasions—1971 and 1987-89—and by democratic means in 1982 and after 1990, but in vain until late 2024. To achieve that goal which many thought was not attainable, it had to form the NPP coalition, reimage itself, rebrand its leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake, compromise its Marxist ideology, soften its stand on liberal economic policies and change its strategy to gain traction in electoral politics. After the 2022 popular uprising, or Aragalaya, which ousted President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, it harnessed a massive wave of public resentment triggered by economic hardships, rampant corruption, abuse of power, nepotism, cronyism, etc., which the Rajapaksa-Wickremesinghe government earned notoriety for. It is now enjoying the fruits of its labor. However, the road ahead is far from smooth.

The Cabinet is full of members who lack experience with governance, and the steep learning curve they are facing is bound to stand in the way of their performance. The people expect quick results. One of the main reasons why President Gotabaya Rajapaksa failed was his inexperience and the appointment of political novices as ministers. Almost all of them lost their seats in last week’s general election.

The sheer extent of public anger at traditional political parties and leaders became evident from collapse of the ITAK and SLMC bastions, which were considered impregnable, in the North and the East. The ITAK could retain only the Batticaloa district, that too with the greatest difficulty.

Anti-politics has transcended all ethno-religious barriers. The NPP, the only untested political force, could capitalize on this phenomenon and gain a turbo boost for its political project. But it is now under the microscope, and anti-incumbency sentiments begin to emerge soon after the formation of any government.

Sloganeering and rhetoric, which the Opposition parties are adept at, are of little use when they are voted into office; they are required to deliver on their election promises unreasonably fast in most cases. Paddy farmers were seen on television, yesterday (18), complaining that they had not received the promised fertilizer subsidy. President Dissanayake may have had funds released, but they have not reached many farmers owing to bureaucratic inefficiency, which usually takes its toll on the popularity of the government in power. Next year, the government will have the state employees protesting in the streets unless it grants them a substantial pay hike, and bring down taxes and tariffs considerably while at the same time ensuring a surplus in the primary account and an increase in state revenue at least up to 15% of GDP. This is no easy task. Worse, it is doubtful whether the new government will be able to avoid the implementation of the imputed rental income tax, which is required to take effect early next year.

The resumption of debt repayment will also happen under the incumbent government in 2028. This must be a worrisome proposition for President Dissanayake, who is also the Finance Minister.

Previous governments could afford to soft-pedal issues such as devolution and even the inordinate delay in conducting the Provincial Council elections because they were not dependent on the votes in the North and the East as such. But the NPP has expanded its support base to those parts of the country as well and has in its parliamentary group about 10 MPs elected from the North and the East. So, the task of living up to the people’s expectations will be even more uphill for the NPP, given the sheer range of issues it has to resolve, including very contentious ones such as the full implementation of the 13th Amendment. A Canada-based Tamil organization has already made several demands, and India is very likely to press for more devolution. President Dissanayake is scheduled to visit India next month, and the Indian government will make use of that opportunity to take up the issue of devolution. The ITAK and other political parties will go all out to recover lost ground and stage a comeback.

There are two elections slated for 2025—provincial council and local government polls— and the new government will have to fulfil at least some of its key promises, including pay hikes, an increase in welfare spending, and tax and tariff reductions by that time if it is not to suffer a midterm electoral setback, which is a nightmare for any government.

An IMF delegation is in town, and it has had talks with President Dissanayake and his team. The President has informed the IMF that his government will work with it in the contest of the recently-obtained popular mandate, according to the Presidential Media Division. IMF bailout programs do not factor in governments’ mandates; they are worked out on the basis of hard economics. Most of the IMF conditions are constricting and entail political costs in the form of tax and tariff hikes and economic reforms, which governments with populist agendas detest.

The survival of the Dissanayake government hinges on the successful completion of the ongoing IMF program, and the possibility of Sri Lanka having to seek more assistance from the IMF cannot be ruled out, according to independent economists. Under no circumstances will the NPP administration be able to incur politically motivated expenditure if it is to retain the IMF lifeline.

The biggest problem with majorities and mandates is that the very people who grant them do not respect them when their expectations are not met, especially when they fail to keep the wolf from the door or have to lose their creature comforts and adopt a difficult way of life. This is the stark reality that no government, however strong, can ignore.