~ By Anne-Marie Schleich

SYNOPSIS

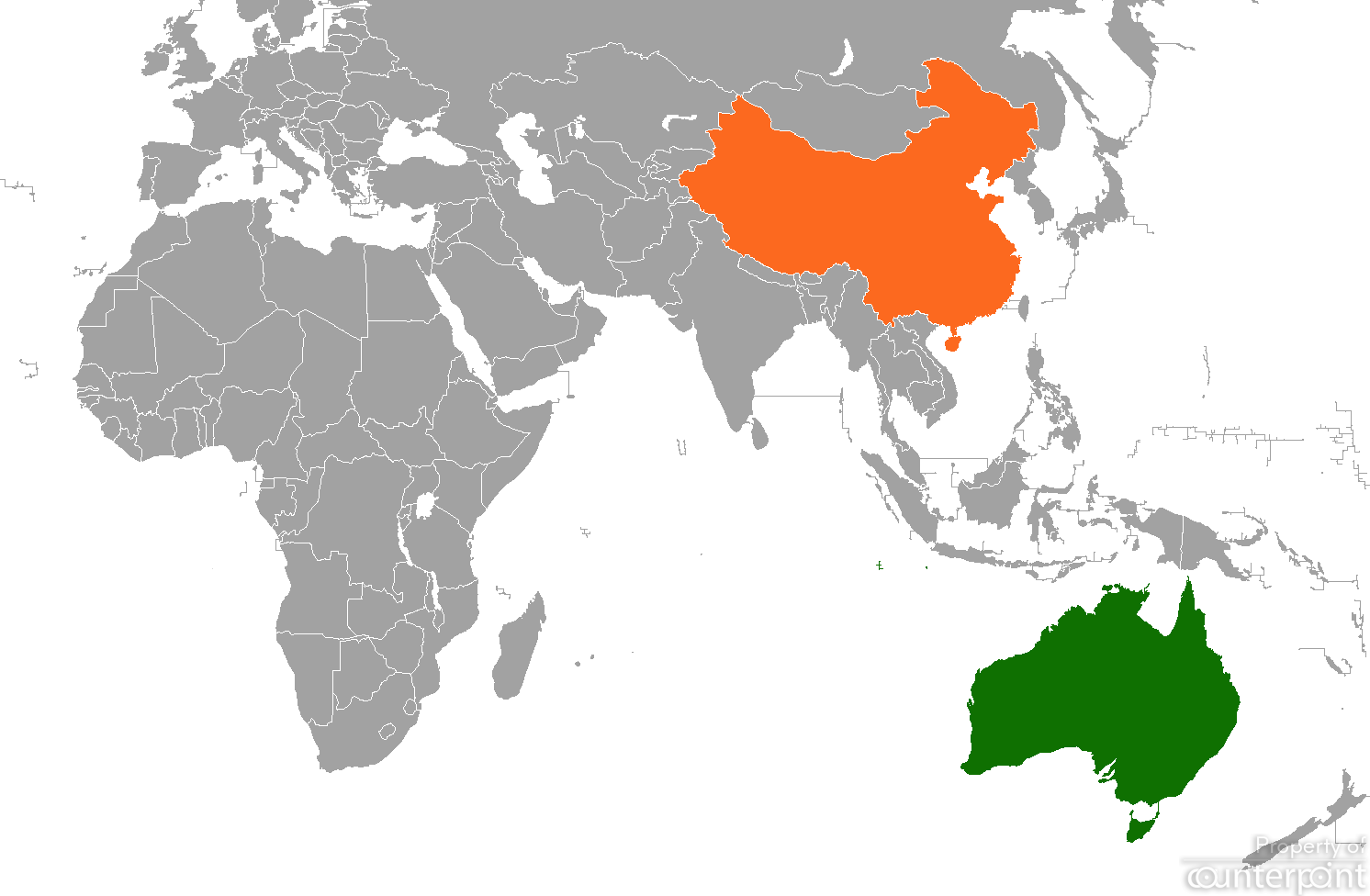

Since April 2020, Australia and China have been embroiled in escalating trade and diplomatic disputes. The relationship between the two countries has deteriorated and is currently at a critical point. Developments on both sides could be right out of a playbook on ‘how to wreck bilateral trade and diplomatic relations’.

COMMENTARY

THE DIPLOMATIC conflict between Australia and China seems to be worsening since it started in 2018. It began when Australia barred Huawei from providing 5G network services in Australia because of security concerns. In February 2020, the Australian Dumping Commission initiated or continued anti-dumping duties on various Chinese steel and aluminium products. And in April 2020, Australia pushed for an international inquiry into the origins of Coronavirus and gathered substantial support among other WHO member countries. It was a move which the Chinese Deputy Ambassador to Canberra termed “shocking”.

China retaliated in May and the following months with import suspensions or import delays of Australian beef, barley, cotton, thermal coal, timber, copper, beer and lobster on the basis of ‘health or consumer protection issues’ or of ‘quota restrictions’. It also imposed higher tariffs on many other Australian goods such as wines and issued Australia travel warnings for Chinese tourists and students. In May, the Australian government decided to continue imposing anti-dumping duties on Chinese imports. In turn, Australia introduced stricter rules for foreign investments in sensitive assets in June. It also suspended in July its extradition treaty with Hongkong in response to China’s introduction of security legislation in Hongkong.

Demand for Apology Which Never Came

In December, Australian Prime Minister Morrison directly responded to an image on the Chinese foreign affairs spokesman twitter account depicting a (likely) fake image of an Australian soldier holding a knife to an Afghani child. PM Morrison demanded an apology from China which never came. In an additional step-up of disputes, Australia in mid-December lodged an official appeal with WTO against China’s anti-dumping and anti-subsidy duties imposed on Australian barley in May.

The Australian Parliament recently also passed a law giving the federal government the power to veto any agreement made by Australian states or universities with foreign countries. This move was widely seen as directed at alleged Chinese interference in Australian politics and economic infrastructure and was possibly another trigger for bilateral relations to further deteriorate.

China remains Australia’s largest trading partner, largest export destination and largest source of imports. China remained Australia’s largest two-way goods and services trading partner in 2018–19, accounting for around 26 per cent (A$235 billion) of total trade. (Second was Japan at 10% of total trade, or $89 billion). According to Austrade, China was Australia’s largest export destination (33 per cent of Australia’s total exports or $153 billion) as well as import source ($82 billion or 19 per cent of Australia’s import bill or $82 billion).

China’s blacklisting of a wide range of Australian commodities and food products has posed serious problems for the affected Australia’s exporters. The government has promised to look into assistance for exporters and also encouraged them to diversify to other markets. This will not be an easy task in the short run considering Australia’s “asymmetrical trade with China” in a number of goods with few alternative destinations.

Political and Economic Dilemma

Australia’s and New Zealand’s trade dependence on China (as well their dependance on China in the tourism and education sector) has created a political and economic dilemma at a time when security and military ties with the US have been intensified under the Trump administration.

Verbal mudslinging, blame games and accusations have increased the temperature in the bilateral spat. China has become increasingly vocal and has blamed Australia for deteriorating relations. Chinese diplomats have also shown a more confrontational and nationalistic approach in their public pronouncements on the various escalations on the Australian side.

Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Zhao said: “Certain people in Australia have clung to a Cold War mentality and ideological biases…”. The same sharpness goes for many remarks of Australian politicians. PM Morrison insisted in mid-November “Australia is a liberal democracy and will not back down…”. For almost a year, there has not been any direct contact between Australian and Chinese government ministers.

The downturn in Australia-China relations is also directly related to Australia’s continued strong and close relationship with the US, especially during the Trump administration. At a time of an increasingly hostile geopolitical tug of war between China and the US, Australia, a regional Pacific middle power, is concerned about growing tensions in the Asia Pacific region.

It has, therefore, recently shored up its relations with its other old Quad partners, Japan and India and US. Signs of this increased cooperation are the visit to Japan by PM Morrison in December and Australia’s first-time participation since 2007 in the India-led maritime exercise ‘Malabar’ together with the US and Japan in November – moves that must have irked China.

Time for Quiet Diplomacy?

The China policy of the Australian centre-right coalition government (Liberal Party and National Party) seems to have played increasingly to a home audience. A number of the government’s parliamentarians belong to a vocal anti-China group. A growing anti-China mood in the Australian political establishment has also been largely supported by a predominantly conservative media landscape belonging to the Rupert Murdoch press conglomerate.

It is interesting to note that Liberal Party MP Andrew Hastie, who has become known since 2019 for his acidic criticism of China, was appointed Assistant Defence Minister in PM Morrison’s cabinet reshuffle in December 2020. Critical voices question Australia’s diplomatic strategy and term it short-sighted. The Labour opposition, especially foreign affairs spokeswoman Penny Wong, has criticised the government’s China policy as being inconsistent and demanded to put bilateral relations back on a more normal track.

What might be needed now is quiet diplomacy and a reduction in nationalistic and assertive statements. Former Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans stressed the importance of lowering the temperature and going back to a more balanced relationship. Interestingly, the new New Zealand foreign minister Nanaia Mahuta already offered that New Zealand might help negotiate a truce between Australia and China.

A renewed dialogue between Australia and China would require less play to home audiences in both countries, less nationalistic grand-standing, greater cooperation on pressing international issues (Gareth Evans called for “working together on global public goods”) and some quiet discussions behind closed doors.

That might just be the right path to make diplomacy work again. An even slightly improved US-China relationship under US President Biden would also be paramount to create a more conducive geopolitical framework. But it will certainly take a lot of effort to restore confidence between China and Australia.

Dr Anne-Marie Schleich is a retired German ambassador who is now residing in Singapore and contributed this to RSIS Commentary. She had served in Bangkok, Islamabad, London and Singapore. She was most recently Consul-General in Australia and German Ambassador to New Zealand.