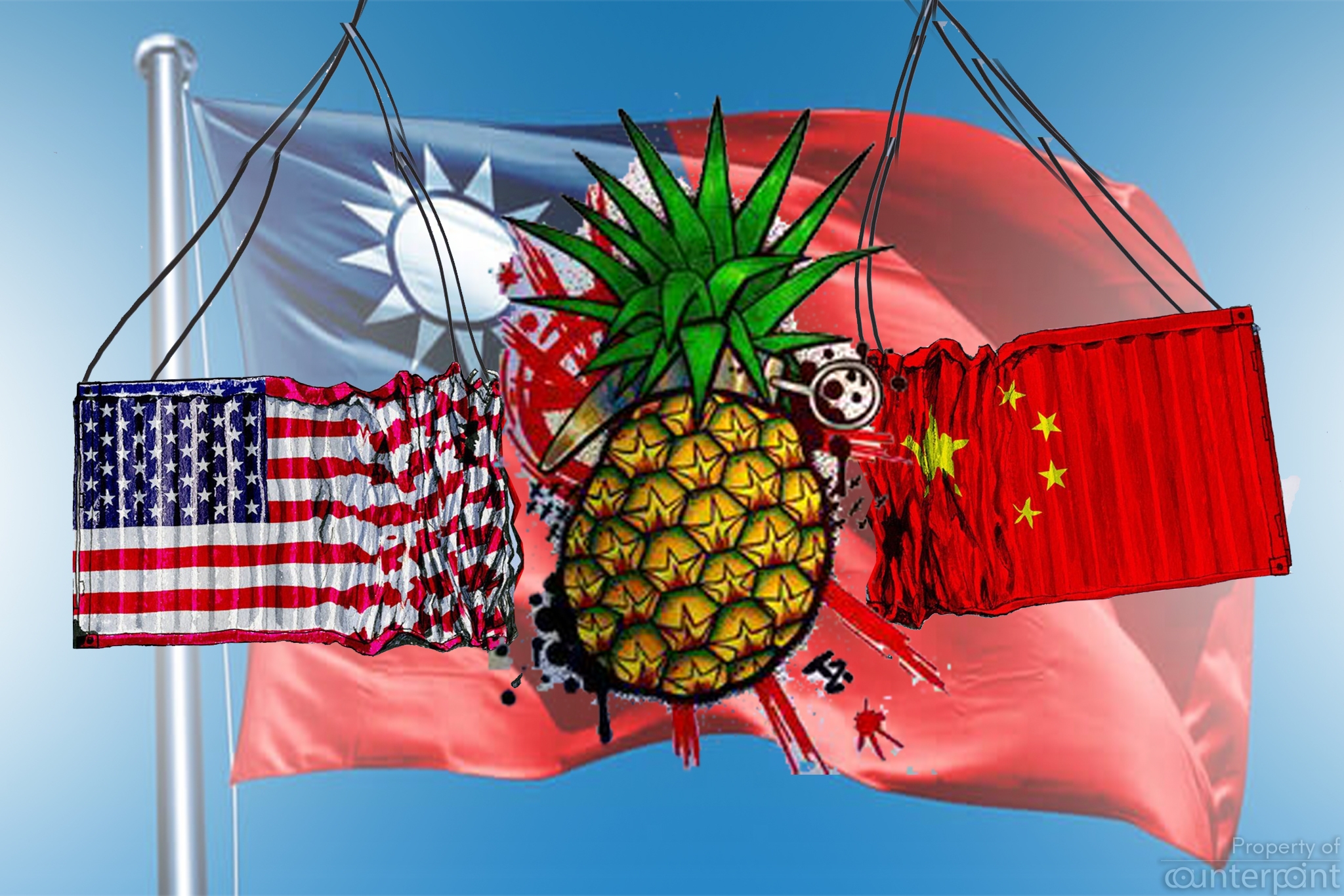

This month, China banned imports of Taiwanese pineapples, the latest in a string of punitive trade measures against democracies that illustrate how China has weaponized its growing economic clout. As the island’s largest trading partner, China buys more than 90 percent of Taiwanese pineapple farmers’ exports. But the island is taking Beijing’s boycott in stride, underlining the potential for what is quickly emerging as one of the Biden administration’s sharpest foreign-policy tools: bringing democratic allies together on China.

U.S. President Joe Biden took the first step in that direction last week. In a joint statement, the leaders of the four democracies in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue—Australia, India, Japan, and the United States—announced their support for an Indo-Pacific region “anchored by democratic?values, and unconstrained by coercion.” To that end, the Biden administration also appears to be taking a strongly pro-Taiwan stance, with the U.S. State Department saying in a statement in January that Washington’s commitment to Taipei is “rock-solid.”

In response to China’s trade ban, the Taiwanese government has launched a chirpy public campaign for the “freedom pineapple” that’s gone viral. From Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen on down, prominent Taiwanese are urging citizens to stand up to China by eating more of the fruit. “After Australian wine, unfair Chinese trade practices are now targeting #Taiwanese pineapples,” Tsai wrote. “But that won’t stop us. … Support our farmers & enjoy delicious Taiwanese fruit!”

Global netizens quickly joined in support of Taiwanese growers, posting photos of pineapple cakes and pineapple shrimp balls. In Taiwan, creative restauranteurs came up with new pineapple dishes, adding pineapple to staples like beef noodle soup. Taiwan’s envoy to the United States shared a picture of herself taking a giant bite out of a whole pineapple at a local Taiwanese farm. Solidarity for “freedom pineapples” flooded in from all corners of the world, including Britain, Denmark, India, and the United States.

Of course, most of the support from abroad has been moral and not economic, since it will take more than just a few days for Taiwanese producers to redirect their exports. Most pineapples in the United States, for example, are sourced from Hawaii and Puerto Rico. But the swift and very public backlash against Beijing suggests there is a growing sense of solidarity among the world’s democracies with victims of China’s economic bullying.

In Europe and North America, China has used economic coercion as a tool for interference 60 times since 2000.

Beijing’s economic tactics aren’t new. China has a history of threatening the private industries of countries whose governments it wants to coerce. Last fall, China slapped tariffs on Australian wine over a list of 14 grievances. Chief among them were press coverage spotlighting China’s human rights abuses and Australia’s call for an independent investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 virus. The Norwegian salmon industry has also gotten the cold shoulder since 2010, when the Nobel Committee in Oslo awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to Chinese human rights activist Liu Xiaobo. By 2015, even the tiny Faroe Islands—a territory of Denmark—sold more salmon to China than all of Norway did. Relations only began to thaw after the Norwegian government signed a joint statement with China in 2016 recognizing the latter’s concerns over the Nobel Peace Prize and pledging not to support actions that undermine “China’s core interests and major concerns.”

China’s bullying is also not limited to import restrictions. In Europe and North America, China has used economic coercion as a tool for interference 60 times since 2000, according to the Authoritarian Interference Tracker, a dataset recently compiled by the Alliance for Securing Democracy. They include threatening the German auto industry over the Chinese company Huawei’s access to constructing Germany’s 5G telecommunications network, issuing a travel warning to damage Canada’s tourism sector following the arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou in Vancouver, and canceling broadcasts of U.S. National Basketball Association games in response to a pro-Hong Kong tweet by Houston Rockets general manager Daryl Morey. As my research with Laura Rosenberger shows, the Chinese party-state does not hesitate to coerce private companies when it disapproves of their messages. These economic tactics are one component of a broader information strategy to bend the truth to the Chinese Communist Party’s wishes.

Unfortunately, the major democracies are more focused on their readiness to counter military aggression from autocrats and have neglected developing a common approach to economic browbeating. A network of defense alliances underpins the liberal order. As important as that is, democracies now also have to find ways to support each other against economic attacks.

So what is to be done? Earlier this month, the Biden administration released a new trade agenda saying that it would use “all available tools” to fight China’s unfair trade practices. Which tools will be used, under what circumstances, and in which ways all remain open questions.

But Biden and his team are likely to resist using Taiwan as a cudgel against China the way Trump did.

One option that former Danish diplomat Jonas Parello-Plesner has proposed is to reach into the Cold War toolkit and enact an economic version of NATO’s Article 5: An attack on one democracy’s economy is an attack on all. Democratic allies would hit back against China with retaliatory tariffs whenever an industry from one country is threatened. While Parello-Plesner’s logic is sound, the idea may be too complex to implement in practice. In the best case, it would require coordination of precise economic tripwires and retaliatory measures on a masterful scale. In the worst case, it could easily snowball into a global tariff war. Limiting the bloc of democratic countries involved in responding to particular threats, such as by region or industry relevance, could simplify the calculus—but leave the others exposed to China picking them off, one by one.

Another option, much easier to implement and likely just as effective, would be to soften the blow to one nation by spreading out the cost among all. When Beijing’s hammer comes down in the form of import bans or tariffs, democracies could agree to increase purchases of affected goods. Where supply chains don’t already exist and are too hard to establish, countries could jump in with aid. In removing the pain, they remove the leverage.

Swift public information campaigns like #FreedomPineapple will be the key to success. And democracies already seem to be learning from each other: A December 2020 campaign led by the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China in support of Australia’s “freedom wine” garnered similar attention. If their governments speak plainly about China, worldwide consumers may jump at the opportunity to support the targeted farmers, fishers, or vintners. Given the high premium the Chinese Communist Party places on information control, visibly losing the public opinion war would show the party that its economic aggression has backfired.

As analysts debate whether the world is headed into a new cold war with China, one distinction is plain: Unlike the Soviet Union, China is deeply integrated in the global economy. Even as some in Washington call for a decoupling, China has overtaken the United States as the European Union’s largest trading partner. It’s no surprise, then, that Beijing is weaponizing this economic interconnectedness for its own interests—including compelling democratic actors into silence on Chinese abuses, from the brutal crackdown in Hong Kong to the Uyghur genocide in Xinjiang.

Democracies must not fall prey to Beijing’s divide-and-conquer strategy. Instead, they must find new ways to blunt the sting together. Citizens of fellow democracies around the world should all be able to eat a Taiwanese pineapple.(Courtesy Foreign Policy Magazine)