Colombo, April 12: Muslims of Ceylon and peninsular India, who are ethnologically similar, were in the vanguard of maritime trade in South and South East Asia from the 3 rd., century BC till the emergence of the Portuguese and other European powers in the 16 th. Century. These Tamil-speaking Muslims of part Arab ancestry were trading peacefully in the region for centuries. But they were eventually outmaneuvered by European traders who were ruthless, armed, and technologically better equipped than the Muslims.

The Europeans not only had the support of a Metropolitan power back in Europe (Lisbon, Amsterdam or London) but also of local kings who flocked to them out of fear or for politico-military support vis-à-vis their local rivals. While European traders were never without a political agenda, Muslim traders were utterly apolitical. Conquest or political dominance over the lands they traded with, was never on their agenda.

The story of the rise and fall of the Coromandel Muslims is told engagingly by Dr.J. Raja Mohamad in his “Maritime History of the Coromandel Muslims” published by the Director of Museums, Government of Tamil Nadu.

The dominant Muslim communities on the Coromandel coast and Ceylon were the Marakkayar (also known as Maraikar, Marikkar or Marcars), the Labbai or Lebbe and Rowther in the Tamil speaking areas. In Kerala, the same ethnic group was known as the Mopla. They were also known as Sonakar or Yavanas (from Yemen). Except in Kerala, where the language spoken was Malayalam, their lingua-franca was Tamil or Arabu Tamil (a mix of Arabic and Tamil or Tamil written in the Arabic script). Almost all traced their origin to what is now Yemen.

These communities were so evident in the ports that English records described the ports on the Coromandel coast as “Moor ports”. Present-day Cuddalore was known as “Islamabad” and Porto Novo (Parangipettai) was “Mohammad Bandar” (Mohammad port), Dr.Raja Mohamad says. While the Marakkayars (boat people) and Lebbais were both expert mariners and traders, the Rowthers made a name for themselves as traders in Arab horses.

The Zamorin, the Hindu ruler of Calicut in Kerala, got Muslims to man his ships. He also decreed that the Arab traders should marry Malayali women and bring up at least one of their sons as a Muslim. Kunjali Maraikkar, who commanded the Zamorin’s navy, bravely took on the Portuguese when they challenged his sovereign. The Maraikkars raided North Ceylon in support of local Tamil rulers who were harassed by the Portuguese.

Muslim interests were hurt when the Portuguese forced the acceptance of the permit system (the “Cartaz” system) to enter ports. Before long, pliant Indian rulers declared that trade in spices, gold and silver were to be a Portuguese monopoly. The Portuguese used their religious affinity with the Syrian Christian merchants and planters of Kerala to prevent the sale of pepper to the Muslims. By 1537 Portuguese Jesuit preacher St. Frances Xavier had converted to Christianity the large fishing community called Paravas on the Coromandel coast and North West Ceylon. With the result pearl trade also went into the hands of the Portuguese. By 1530, the Muslims had also lost their monopoly over trading in horses.

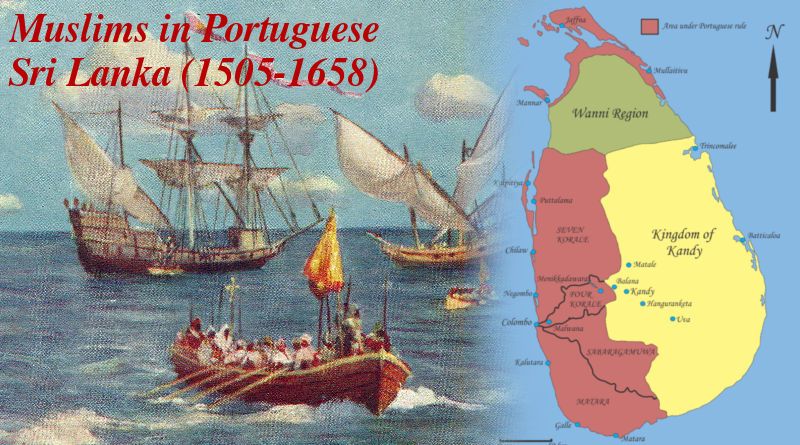

To control trade in the entire region, the Portuguese established their power over key maritime choke points like Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, and Malacca in South East Asia. Ceylon also had passed into their hands quite easily.

Muslim traders from the Coromandel Coast and Ceylon had set up a number of settlements in Malaya and other parts of South East Asia. In their paper entitled: “The Changing Identities of the Tamil Muslims from the Coromandel Coast to Malaysia: An Etymological Analysis” Shaik Abdullah Hassan Mydin and Mohammed Siraaj Saidumasudu say that the Malayan Sultans relied on the Coromandel Muslims for the progress and well-being of their States including royal trade.

“Such a scenario paved ways to the development of Tamil Muslims in Johor, Perak, Kedah and Acheh in the 17th and 18th. Centuries. As their importance and influence in trade grew, the Sultans of the Malay states and the aristocrats appointed them as royal merchants or Saudagar Rajas. Furthermore, they even married into royal families,” Mydin and Saidumasudu say.

However, Muslims in South India and South Indian-origin Muslims in South East Asia, did not keep pace with the growth of knowledge, especially technical knowledge through a Western education out of fear of losing faith in Islam in the process. Both in South India and Ceylon the Muslims shunned European-run schools. Dr.Raja Mohamad noted that even though European steamships had started plying on the Coromandel coast in 1826, Muslim mariners stuck to sailing ships till 1900.

Ceylon

As in peninsular India, in Ceylon too, international trade was in the hands of the Arabs and their descendants through marriage with locals. In his paper “Muslim contribution to maritime trading activities in Sri Lanka,” in “Maritime Heritage of Sri Lanka” (The National Trust Sri Lanka) Asiff Hussein says that when the “storm tossed ships of Dom Francisco de Almeida made landfall in the port of Galle (1505 CE), he found many Moors who were engaged in loading cinnamon and elephants to be taken to Cambay.” Cambay is in Gujarat in Western India.

Though the Portuguese hated the Muslims, and their sovereign in Lisbon wanted Muslims to be banished from Ceylon, the Portuguese Governor of Goa (the headquarters of the Portuguese empire in the Eastern hemisphere), Fernao de Albuquerque, wrote on 11 February 1620 explaining that the Moors were “not prejudicial to Portuguese interests in the island,” and that their trading and maritime skills could be used by the Portuguese.

Like the Portuguese, the Dutch too were fierce traders and proselytizers but at times they also used the Moors to further their trading interests, Hussein says. In 1791 and 1792, they used Muslims mariners Sinna Pulle Marikkar and Lebbe Thambi Marikkar. A German in the service of the Dutch, Johann Wofgang Heydt, refers to a large of number of Moors exporting coconuts, coir, and arecanut to Madras, Calcutta and Bombay and other ports in India and bringing back rice and cloth. Colonial Secretary in Ceylon James Emerson Tennent noted that in the 1840s, the Moors of Batticaloa had a monopoly of both internal and international trade in that area.

Given their preoccupation with maritime trade, the Muslims of Ceylon (dubbed “Moors” by the Portuguese) were closely connected to the ports of Ceylon. Their settlements were predominantly coastal. They were found in large numbers in Trincomalee, Jaffna, Mannar, Kudiraimalai, Puttalam, Colombo, Beruwela and Galle.

But as in the case of the Muslims of the Coromandel coast and the rest of South India, the educational backwardness of the Ceylonese Muslims eventually stood in the way of their progress in all fields including international trade. Fear of conversion to Christianity prevented them from acquiring an English education which in turn kept them away from technological progress and the adoption of modern techniques.

The gap between them and the Europeans kept widening till some progressive Muslim leaders emerged in the early 20 th. century who took steps to improve their educational levels and general awareness.

END

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...