By Vishvanath

The incumbent SLPP-UNP government is a contradiction in itself. It is doing exactly the opposite of what those who voted the SLPP into power expected. This fact became manifestly clear from a statement President Ranil Wickremesinghe made at a recent ceremony where freehold land title deeds were distributed among a group of beneficiaries of the Urumaya programme.

President Wickremesinghe said that when he was the Prime Minister of the UNP-led UNF government (2001-2004) he had tried to carry out the Urumaya programme to grant land rights to the people who were either without land or occupying state lands under a license system, but a judicial decision had stood in his way. He however stopped short of mentioning the Regaining Sri Lanka programme. Criticising the judgement in question, he vowed to go ahead with his land distribution programme. The legal and political significance of that presidential statement was apparently lost on political commentators perhaps due to the sheer number of issues they have to deal with on a daily basis.

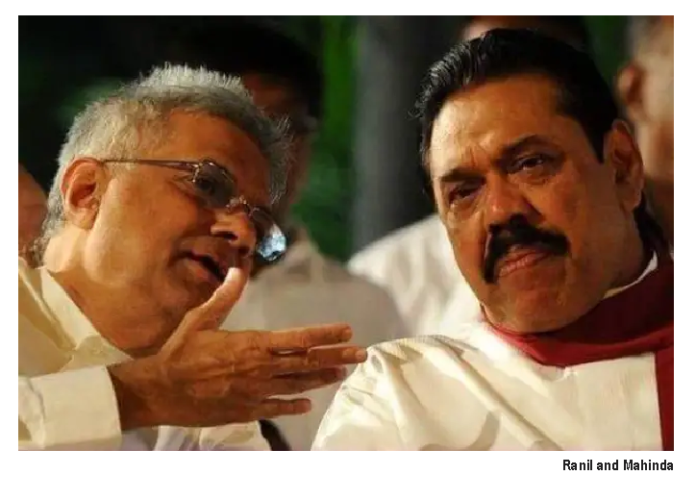

Differences between the SLPP and the UNP have come to a head with the stalwarts of the former publicly advocating for the implementation of the Mahinda Chinthanaya. They have sought to leverage the bargaining power derived from President Wickremesinghe’s efforts to enlist their support for his presidential bid, to revive the Mahinda Chinthanaya.

The SLPP insists that in case it opts not to contest the presidential election it will back a presidential candidate who agrees to implement the Mahinda Chinthanaya, the implication being that President Wickremesinghe will have to make a volte face and embrace the SLPP’s core ideology. Wickremesinghe’s politico-economic ideology, which underpins what the current government is doing, is diametrically opposed to Mahinda Chinthanaya.

In fact, Mahinda Chinthanaya was the policy and ideological alternative offered by the Rajapaksas to the Regaining Sri Lanka programme in 2005; they repeatedly obtained popular mandates to implement it until 2015, when a UNP-led coalition came to power. The Yahapalana collective obtained a popular mandate by offering something similar to the Regaining Sri Lanka programme, but it was rejected by the people at the local government, presidential and parliamentary elections in 2018, 2019 and 2020, respectively. The UNP suffered its worst ever electoral defeat in the 2020 general election, with the architects of Regaining Sri Lanka even losing their parliamentary seats. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s policy programme, Vistas of Prosperity and Splendour’ the people voted for in 2019, was only an extension of Mahinda Chinthanaya.

It has been argued in some quarters that Vistas of Prosperity and Splendour lost its relevance, validity and legitimacy the day the people took to the streets and ousted Mahinda Rajapaksa and Gotabaya Rajapaksa as the Prime Minister and the President, respectively, in 2022. But the fact remains that there has been no popular mandate for the implementation of the Regaining Sri Lanka programme under a President, who was elected by the SLPP in Parliament to complete the remainder of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s presidential term. The mega policy/ideological shift we are witnessing on President Wickremesinghe’s watch should have been endorsed by the people for it to gain legitimacy.

This comment is not a critique of either the Regaining Sri Lanka programme or Mahinda Chinthaya/Vistas of Prosperity and Splendour. It only attempts to examine the fundamental differences between the two policy programmes and ideologies and discuss their impact on the way the public perceives and responds to government policy, and the politico-social ramifications of the ever-expanding trust deficit, which has come to characterise the relations between the electors and the elected.

Adversity is said to make strange bedfellows, and the validity of this truism became obvious in 2022, when a desperate President Gotabaya Rajapaksa invited even his bitterest critics such as Field Marshal Sarath Fonseka and JVP leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake to take over as the Prime Minister. They did not heed his call, and finally a union between the SLPP and the UNP came into being. In a dramatic turn of event, the SLPP went so far as to defeat the candidate representing it when the parliament elected the President, in July 2022, following Gotabaya’s ouster; it elected Wickremesinghe at the expense of the SLPP candidate, Dullas Alahapperuma, backed by SLPP Chairman Prof. G. L. Peiris himself and the Opposition. That election caused another split in the SLPP with several of its MPs voting with their feet. Over a dozen SLPP dissidents have since pledged their support to the SJB.

The SLPP-UNP union remained strong despite the differences between the two parties until it overcame threats and challenges emanating from the anti-government protesters. The SLPP is now at a political crossroads. If it fails to gain a boost from the upcoming presidential election, it will not be able to make a comeback in the foreseeable future. It cannot find a formidable presidential candidate and chances are that it will have to throw in its lot with President Wickremesinghe. But it cannot support the UNP in the presidential race on the latter’s terms.

Weakened as the SLPP is, it cannot be written off as a spent political force. It is not a shadow of its former self, but it has considerable political and electoral strength left. The next presidential election is bound to be closely contested, and the possibility of none of the candidates being able to obtain 50% plus one vote to secure the presidency straightaway cannot be ruled out. Hence President Wickremesinghe’s efforts to secure the SLPP’s support. He has won over a group of SLPP MPs including the Chief Government Whip in Parliament, Minister Prasanna Ranatunga. But the question is whether they will be able to deliver enough votes to Wickremesinghe if the SLPP decides against supporting him.

The SLPP and President Wickremesinghe are already at loggerheads, with the latter being resentful towards the latter, having failed to have a snap general election held and stop crossovers from its ranks to the UNP. At the same time, the SLPP and the UNP will be at a disadvantage in the presidential race if they break ranks at this juncture and take on each other. The issues they tried to wish away and/or manage to suppress to sustain their uneasy union have resurfaced with a vengeance. Prominent among these seemingly irreconcilable issues is the clash of Mahinda Chinthanaya and the Regaining Sri Lankaprogramme, besides the Rajapaksa family’s concerns about the future of their political dynasty, which Namal Rajapaksa has proudly claimed is about 100 years old.

It looks as if the union between the SLPP and UNP were coming to an end. But horse trading is on and anything is possible in Sri Lankan politics, where expediency and self-interest take precedence over principles and morality. The success of the ongoing negotiations between the Rajapaksa family and President Wickremesinghe hinges on their ability to reach a compromise on their competing ideologies and agendas. They will have to do so fast with only days to go until the declaration of the presidential election, which is an unnerving proposition for the SLPP, the UNP and all others who are aware of their electoral weaknesses despite their boastful claims meant for the consumption of the public.

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...