P.K. Balachandran

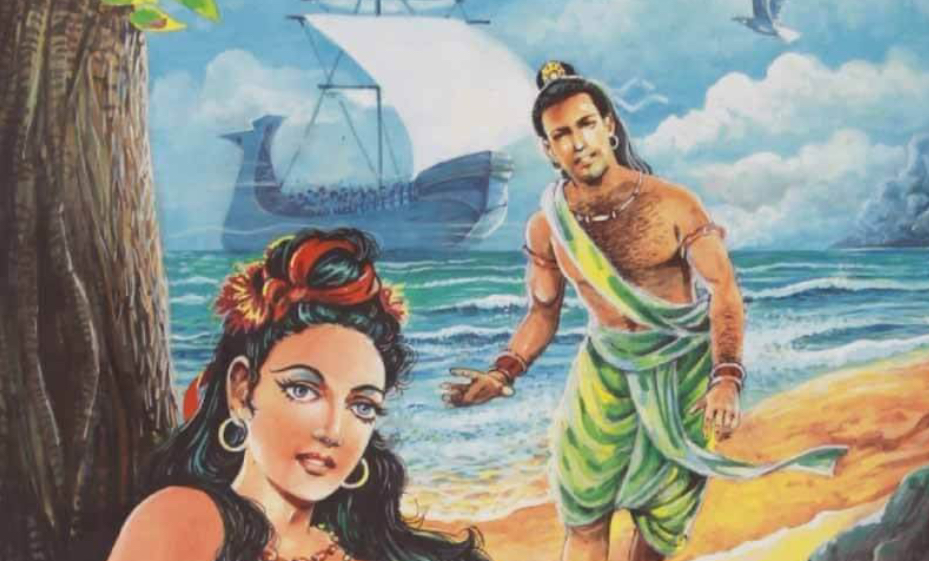

Colombo, January 23: Ceylon (as Sri Lanka was known until 1972) has had a special link with Bengal. Popular myth has it that the Sinhaleseare descendants of an expatriate Bengali Prince,Vijaya. That early link snapped. But it was re-established in the last two decades of the 19 th.Century, thanks to Anagarika Dharmapala, the Ceylonese Buddhist revivalist and anti-British radical freedom fighter.

Colombo, January 23: Ceylon (as Sri Lanka was known until 1972) has had a special link with Bengal. Popular myth has it that the Sinhaleseare descendants of an expatriate Bengali Prince,Vijaya. That early link snapped. But it was re-established in the last two decades of the 19 th.Century, thanks to Anagarika Dharmapala, the Ceylonese Buddhist revivalist and anti-British radical freedom fighter.

Ceylon-Bengal relations and Dharmapala’scentral role in shaping that relationship are engagingly described by Dr.Sarath Amunugamain his book entitled: “The Lion’s Roar: Anagarika Dharmapala and the making ofmodern Buddhism (Vijitha Yapa, 2016).

Dharmapala was intimately connected to the Bengali elite called the Bhadralok (Bengali for “respectable people”). His Bhadralok linksimmensely helped him in his fight to retrieve the Buddhagaya shrine in present-day Bihar, for Buddhists, from the hands of an influential and wealthy Hindu priest. Dharmapala’s aggressive political style, which he displayed on his return to Ceylon, was also shaped by the Bengali radicals he had been in close touch with.

From 1891, when he first visited Calcutta, to the time of his death in Sarnath in 1933, Dharmapala spent the better part of his life in India. “India became the object of my love in January 1884,” he had said. His love affair with India began in 1880 when he met Theosophists Col. Henry Olcott and Madam Helena Blavatsky in Colombo. The Theosophists had already established a base in Calcutta with the help of the Bhadralok. And when Dharmapalawent to Calcutta in 1891, he struck a fruitful and lasting friendship with Babu Norendranath Sen, a rich man who owned and edited Indian Mirror. Soon this paper would become Dharmapala’s voice.

Having heard from Sri Edwin Arnold that the Buddhagaya shrine was in an extremely bad state, Dharmapala went there on January 21, 1891 and was moved to tears by the ruins. “This encounter changed Dharmapala’s life and had far-reaching consequences for Sinhala-Buddhists,” Dr.Amunugama writes. Inspired by the institution-building work of the Theosophists, Dharmapala vowed to set up an organization for “reclaiming and preservation of Buddhist sacred sites in North India.”

As the first step, Dharmapala headed for Calcutta where he met (and was a guest of) Babu Neel Comul Mukherjee, Secretary of the Bengal Theosophical Society. On his return to Ceylon via Burma, Dharmapala established the Mahabodhi Society (MBS), with an aim “to revive Buddhism in India, to disseminate PaliBuddhist literature, to publish Buddhist tracts in the Indian vernaculars, to educate the illiterate millions of Indian people in scientific industrialism, to maintain teachers and Bhikkusat Buddhagaya, Benaras, Kusinara, Savaththi, Madras and Calcutta, to build schools and Dhamashalas at these places and to send Buddhist missionaries abroad.”

The renowned Ceylonese monk, HikkaduweSumangala Thera, was made President of MBS. Dharmapala also got four Ramanna Nikayamonks to go to Buddhagaya and live there. “After 700 years we have raised the banner of Buddhism in India,” he wrote triumphantly.

But the new priest at the Buddhagaya Hindu shrine, Krishna Dayal Giri, opposed the Ceylon Buddhists’ presence and evicted them. Dharmapala sought the help of Neel ComulMukherjee who accommodated the MBS in his house.

In the last two decades of the 19 th.Century and the first decades of the 20 th., Bengal was in turmoil both in the field of religion and politics.The political ambitions of the English-educated Bhadralok were clashing with British domination. Simultaneously, there was a cultural and religious assertion by the Hindu majority as a reaction to state-backed Christian evangelism. Dharmapala was caught in thevortex of these conflicts. He felt the need to harness the emerging trends for the cause of Buddhism in India, especially his mission to liberate Buddhagaya from the clutches of the Hindu landlord cum priest.

The politico-religious-cultural churning in Bengal had spawned two rival associations – the British India Association, representing the conservative Bhadralok, pushing Hindu interests, and the Indian Association,representing the dynamic and modernistic Bhadralok, essentially the Bhadralok of Calcutta, educated in English and drawn from the professions. However, the latter also took up popular Hindu causes looking at them from the point of view of Indian nationalism.

Surendranath Banerjea was the leader of the Indian Association. According to Dr.Amunugama, Banerjea “ruled the roost” in Bengal and was also Bengal’s link with the nascent Indian National Congress, which was to become the premier organization in the fight for India’s independence. Dharmapala latched on to the Surendranath Banerjea-led group and came to know top Indian political and renaissance leaders like Rabindranath Tagore and Swami Vivekananda intimately. Dharmapala and Vivekananda were both at the Parliament of World Religions in Chicago in 1893.

However, like the Theosophists, Dharmapalawas uncomfortable with the rising Hindu sentiment which feared that any quarter or fillip given to the Theosophists and Buddhists, would injure the Hindu revivalist cause. Realizing that his mission regarding the Buddhagaya shrine would suffer if he allowed differences between the Hinduism and Buddhism to grow, Dharmapala delivered a lecture in Albert Hall in Calcutta in which he was at pains to demonstrate the “non-threatening character” of the Buddhagaya movement.

Significantly, this was applauded by the liberal Bhadralok including Norendranath Sen’s Indian Mirror which called for a place for Buddhists in Buddhagaya on the plea that there had been no historical animosity between Hinduism and Buddhism.

But given the strength of the Hindu lobby, Dharmapala “wheeled in the heavier gun” Theosophist Col. Henry Olcott who turned the tide in his favor through his speeches. But unfortunately for Dharmapala, Olcott (at the suggestion of fellow Theosophist Annie Besant, and also at the instance of his spiritual ‘Master’) decided to go soft on Hinduism in India, while supporting Buddhism in Ceylon. Olcott left the Mahabodhi Society too. To Besant and Olcottthese seemed politically expedient. This led to Dharmapala’s quitting the Theosophical Society.

Despite the opposition of the Hindu lobby, some leading members of Calcutta’s Bhadralokopenly spoke in favor of Dharmapala’s mission. Raja Jotindro Mohan Tagore declared that “the movement for placing in the hands of the Buddhists, the Buddhagaya Temple is so consistent with justice, that no reasonable man can take exception to it.” But to accommodate the Hindu sentiment he suggested that images of Hindu Gods and Goddesses also be accommodated in the shrine.

Dharmapala had the support of Rabindranath Tagore also. Tagore lauded the establishment of a Buddha Vihara at College Square in Calcutta, included Buddhism in his poems and songs, and counted among his friends Buddhist-national leaders in Ceylon like D.B.Jayatillaka, W.A. Silva and F.R.Senanayake.

Meanwhile, the situation in Buddhagaya was hotting up with the Hindu priest getting a favorable ruling from the Calcutta High Courtagainst Dharmapala’s plea. The Japanese-donated Buddha statue at the shrine was to be moved to the Calcutta Museum. However, two Indian newspapers Behar Times and Indian Mirror came to Dharmapala’s aid by carrying out a strong campaign for his cause. They said that it would be wrong to turn away Buddhists who also considered India as their Holy land. To reach the non-English speaking literati, Dharmapala tapped the popular Bengali paper Hitavadi . Simultaneously, he reached out to the Hindu nationalists and got Swami Vivekananda to say that while “the Buddha provided Hinduism its heart, the Brahmin provided its head.”

Having seen Hindu radicalism on the rise in Bengal, Dharmapala applied the radical approach on return to Ceylon. While other Ceylonese nationalists were soft and constitutional in their stance against the Britishand Christian missionaries, Dhramapala went hammer and tongs at both. He riled against the Westernized Ceylonese elite and asked them to take to the ways of the Indian nationalists. The British banned his paper, Sinhalala Bauddhayafor its radical content.

Dharmapala died in Sarnath, a Buddhist pilgrimage center in India, in 1933, but without achieving his objective of securing Buddhagayafor Buddhists. It was only after India’s independence that the objective was achieved.

END