China’s efforts in peace-brokering are based on a mix of economic interest, conscious neutrality and chutzpah.

By P.K.Balachandran

Colombo, January 23: Given its rapid rise as an economic giant, China has been wanting to foster world peace by a variety of means, including brokering peace between warring parties, whether sovereign countries or no-State actors.

China’s venture is based on observing neutrality between the contesting or warring parties; non-interference in internal affairs of sovereign countries; laying stress on infrastructural development; and fostering global schemes such as the Global Development Initiative (GDI), Global Security Initiative (GSI) and the Global Civilizational Initiatives (GCI).

China has so far played a constructive role in bringing about transitions in the perpetually disturbed Afghanistan; it has helped warring Iran and Saudi Arabia strike a deal; and has initiated ceasefires agreements in war-torn Myanmar.

In all this, the bottom line has been a combination of China’s self-interest (mainly economic) and the long term and sustainable interest of the parties in conflict.

Myanmar Ceasefire

China’s latest bid for peace has been in Myanmar, a disturbed country no power in the world has wanted to enter as a peace maker, partly because of the complexity of the problem and partly because Myanmar has no strategic value yet.

In the third of week of January 2025 China announced that it has mediated a ceasefire between the military government of Myanmar and an Ethnic Armed Organization (EAO) called the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). The Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning said in Beijing: “We hope that all parties will maintain the momentum of ceasefire and peace talks, earnestly implement existing common understandings, take the initiative in deescalating the situation on the ground, and further negotiate and settle relevant issues through dialogue.”

She added that China stands ready to actively promote talks and provide support for the peace process in northern Myanmar.

The MNDAA is made up of the ethnic Chinese Kokang minority inhabiting the North Eastern Myanmar bordering China. The MNDAA is a member of the “Three Brotherhood Alliance”. Myanmar’s EAOs including MNDAA have been fighting for decades for greater autonomy from the central government based in Yangon.

The EAOs are loosely allied with the People’s Defence Force (PDF), the pro-democracy armed resistance group among the majority Bamars, which was formed after the army’s February 2021 coup. The PDF’s membership is largely drawn from the majority Bamar community but is bitterly opposed to the junta, though the latter is composed entirely of Bamars.

Writing in The Irrawaddy, Bertil Lintner, a Swedish expert on Myanmar, says that China has once again shown that it is the “only outside power with the means, capacity, and motivation” to intervene in Myanmar’s internal conflicts. China has a vital interest in keeping the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) going. The CMEC provides China’s landlocked South Western provinces with an outlet to the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean.

China has had close military and political relations with some ethnic groups living near its Western border, in addition to having close military ties with the ruling junta in Yangon. The Kokangs and Wa who inhabit the Sino-Myanmar border on the Myanmar side have had close links with China.

In early December 2024, the MNDAA passed a resolution to opt for Chinese arbitration. The MNDAA and its close ally, the Palaung Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), said that there will not “march on Mandalay” and escalate the conflict with the junta and antagonise the majority Bamar community. The TNLA said that it would “always cooperate with China’s mediation efforts and continue to cooperate to achieve good results.”

The third member of the “Brotherhood Alliance”, the Arakan Army (AA), which has managed to overrun most of its homeland of Rakhine State bordering Bangladesh, announced in December 2024 that it is ready to negotiate with the military regime.

Western peace-making outfits have had little success in Myanmar so far. Lintner says that nothing constructive can be expected from ASEAN. ASEAN’s “Five-Point Consensus” formula, which was adopted a few months after the February 2021 coup and which called for the immediate cessation of violence, constructive dialogue and humanitarian assistance to areas which had been affected by the fighting, was a non-starter.

As Lintner put it, ASEAN has never, in its 58-year history, managed to solve a single bilateral conflict or dispute between its 10 member countries, let alone end an internal crisis in a member state. Western countries have outsourced the Myanmar issue to ASEAN without looking at its antecedents, Lintner says.

Kachins, Karens and Chins Defy

Lintner points out that not all EAOs are eager for peace. The Kachin Independence Army (KIA) ignored China’s 2024 request not to seize control of the border town of Pangwa. China has even less influence in areas along the Thai border where Karen and Karenni resistance forces are active. China has no control over the Chins in the west bordering India.

But there is a question nobody seems to have asked: “Will the Bamar, who are the majority community in Myanmar, agree to the ethnic groups’ demand for autonomy or independence?” True, the mainly Bamar People’s Defence Forces (PDF) has been fighting alongside the ethnic armies against the junta, but fighting for democratic institutions is one thing and rendering justice to ethnic and religious minorities is another ballgame altogether.

As a mediator, China will have to face this issue of demands and goals. Can China view its economic interests in isolation from political issues? Lintner has another interesting doubt: whether the emergence of a strong, peaceful, democratic, and federal Myanmar, is in China’s strategic interest?

Be that as it may, there is another hard reality to be faced, and that is: It is highly unlikely that the Myanmar junta will be defeated any time soon. And it is doubtful whether the resistance will be strong and united enough to unseat the junta.

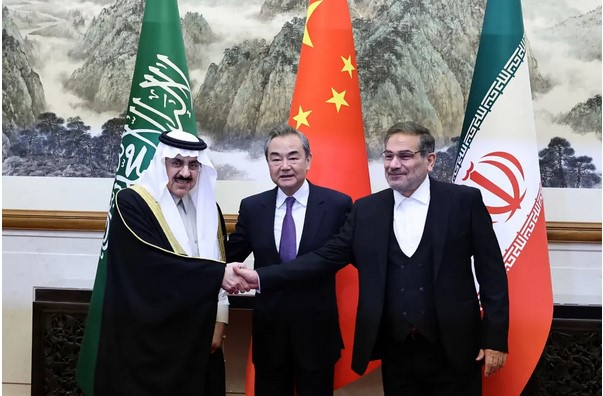

Saudi-Iran Deal

In March 2023 China successfully mediated a peace treaty between Iran and Saudi Arabia. According to Barnett R. Rubin of the Stimson Centre, both Iran and Saudi Arabia wanted to have good relations with China. And they did not see China as a threat. These two factors helped China mediate.

Rubin says that there is a lesson for the US in this. The US has to negotiate with Iran one day, and to do so, it needs to have some sort of relationship with Tehran. It does not have that now. If President Trump is to negotiate a deal with Iran, he could take the help of China which already has Iran’s ear. And China might respond favourably as, like the US, it also wants peace in the Persian Gulf.

Trump could take the help of China to bring a ceasefire in Ukraine too, as China is seen by both Putin and Zelensky as being neutral. In fact, China had wanted to mediate in Ukraine. Trump too has been saying that he will mediate. Trump could use Putin’s economic dependence on China to make the Russian leader see reason.

Rubin has discussed China’s role in the mediation efforts in Afghanistan. China is interested in tapping Afghanistan’s natural resources (lithium, coal, iron, copper, oil, and gas) and hence the search for peace. Insecurity and conflict in Afghanistan has threatened the security of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Central Asia and Pakistan, especially the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

At various stages China had tried to mediate in conflicts between Afghanistan and Pakistan and between the Afghan government, the Northern Alliance and the Taliban. It did so through both confidential and public meetings, bilaterally, trilaterally and quadrilaterally, involving the U.S., Pakistan, Afghanistan and the Taliban. In all these meetings, China’s neutrality had ensured its acceptability as a mediator.

Even in the midst of the war and talks, Chinese companies had been trying to invest in the extraction of natural resources from Afghanistan. In 2007, a major mining firm had signed a contract to open what has the potential to be the world’s largest copper mine in Mes Aynak, in the Logar province. Other companies also signed a joint venture agreement with Watan Industries, an Afghan company, to exploit the oil and gas resources of the Amu Darya basin in Jawzjan province.

To sum up, a mix of economic interest, conscious neutrality and chutzpah has helped China navigate the turbulent waters of mediation between sworn enemies, score some successes and raise hopes for a more productive future as a peace maker.

END

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...