by Vishvanath

All political leaders, especially President and JVP-led NPP leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake and SJB chief Sajith Premadasa are on tenterhooks, given the extremely high stakes they have in today’s parliamentary election. Unless they improve the electoral performance of their parties significantly, they are likely to face challenges to their leadership.

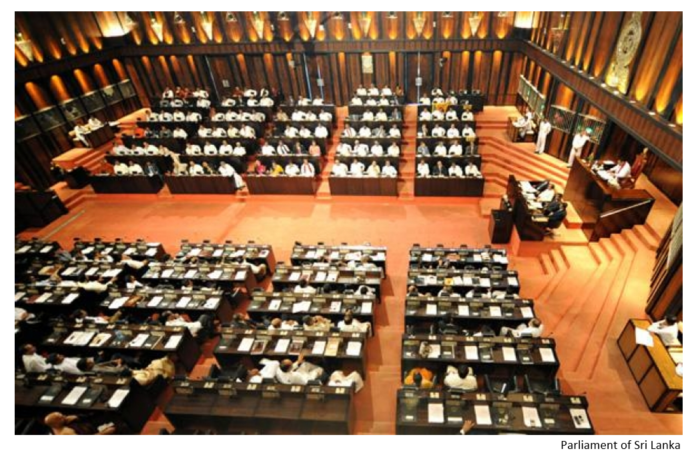

President Dissanayake has to gain control over the parliament to consolidate his power. The challenge before him is to obtain 113 or more seats in the 225-member parliament,where his party, the JVP-led NPP, had only three MPs including himself. In other words, he has to obtain 110 more seats to form a government.

The SJB will experience more internal problems with the morale of its rank and file sagging further unless Premadasa succeeds in giving the NPP a run for its money in today’s race. He has his work cut out to do.

UNP leader and former President Ranil Wickremesinghe will also be in trouble unless the UNP-led New Democratic front and the CWC, which is contesting under the UNP banner, secure at least 10 seats or more.

The ITAK, which dominates the North and the East, had 10 seats in the last parliament, and it will have to retain them or win more, if it is to prevent an erosion of its vote bank. The NPP has been campaigning really hard in the North and the East and if it succeeds in securing at least a single seat, in today’s election, it will gain a bridgehead in northern politics.

President Dissanayake’s stakes in today’s election are much higher than those of others, for no President can exercise his or her executive powers or perform his or her functions properly without control over the parliament.

One may recall that during J. R. Jayewardene’s presidency, the then Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa lamented in the parliament that he was as powerless as an office assistant. What he said was true. When the President is the leader of the party that controls the parliament, he or she is extremely powerful, so much so that Jayewardene once bragged that the only thing he could not do with his executive powers was to make a man a woman, and vice versa. But the Prime Minister becomes more powerful than the President to all intents and purposes when they happen to represent two different parties, or the latter belongs to the same party as the former but is not its leader, as was the case when Gotabaya Rajapaksa was the President.

Governments become dysfunctional when the President and the Prime Minister clash. We have seen this happen twice in this country. President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe were at daggers drawn from 2001 to 2004. The country’s national security suffered as a result while the LTTE was preparing for the next phase of the Eelam war. President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Wickremesinghe were at loggerheads during the latter part of the Yahapalanagovernment (2015-2019). Their clashes adversely impacted national security, and the Easter Sunday terror attacks happened. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa also had his position undermined by the SLPP parliamentary group, which was controlled by his brother, Basil. He failed eventually and had to resign amidst a popular uprising.

The party which secures the presidency usually wins a general election that follows, but there is no guarantee that it can form a stable government. All winners in presidential contests since 1982, except Dissanayake, have polled more than 50% of votes. But only three of them, namely Ranasinghe Premadasa, Mahinda Rajapaksa and Gotabaya Rajapaksa, could enable their parties to win general elections with absolute majorities under the Proportional Representation system. They did so under extraordinary circumstances—the second JVP insurrection, war victory and fear of ISIS terrorism, respectively. One can argue that the current economic crisis and the resultant frustration of the public will have a bearing on the outcome of today’s election.

The UNP under President Premadasa’s presidency obtained 125 seats in the 1989 general election, which was however marred by violence and large-scale rigging; the JVP resorted to mindless violence to sabotage elections during that period. The 1994 parliamentary polls preceded that year’s presidential election, and the SLFP-led People’s Alliance (PA) could obtain only 105 seats in the parliament, and had to enlist the support of some other parties such as the SLMC and the EPDP to muster a working majority. President Kumaratunga won a second term in 1999, but her party, the PA, received only 107 seats in the general election the following year. Her government fell in 2001, when the UNP-led UNF wrested control of the parliament; the UNP, however, could win only 109 seats. She sacked that UNP administration in 2004 and regained power in the parliament by holding a snap general election, but the SLFP-led United People’s Freedom Front (UPFA) won only 105 seats. However, it formed a government with the help of some MPs of other parties, and became stronger after Mahinda Rajapaksa’s victor in the 2005 presidential election.

A political party was able to muster a two-thirds majorityin the parliament for the first time under the PR system in 2010, when the UPFA, under the leadership of re-elected President Mahinda Rajapaksa obtained 144 seats and engineered crossovers from the UNP. Both presidential and parliamentary elections were held in that year while President Rajapaksa’s popularity was at its zenith due to the defeat of the LTTE.

Maithripala Sirisena became President in 2015, but the UNP, which enabled him to win the January 2015 presidential election, could obtain only 106 seats in the general election that followed about seven months later. The SLPP, which the Rajapaksas formed after breaking away from the SLFP, in 2016, obtained 145 seats in the 2020 general election, which was preceded by Gotabaya’s election as President. The deterioration of national security, which led to the Easter Sunday terror attacks in April 2019, ruined the UNF’s chances of winning much to the advantage of the SLPP.

Sri Lanka’s electoral politics is full of surprises, and therefore it is not possible to make predictions about elections, especially parliamentary polls. However, what is remarkable about today’s election is that the frontrunners are newly formed alliances.

The JVP-led NPP was founded in 2019 and the SJB in 2020. The SLPP, which was formed in 2016, has been reduced to a minor party, and the SLFP and the UNP are not in a position to contest election under their own steam. The leftist parties, such as the Communist Party and the LSPP, have become constituents of alliances led by other parties.

The ‘old parties’ however cannot be written off. No government can remain popular forever, and in opportunities present themselves, from time to time, for political parties to make a comeback. Whoever would have thought the JVP would be able to win the executive presidency?

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...