by Vishvanath

Sri Lankan politics may be divisive and obnoxious, but it is always exciting nonetheless; it is full of dramatic twists and turns. Political circuses keep coming to town often, so to speak, and they overshadow everything else.

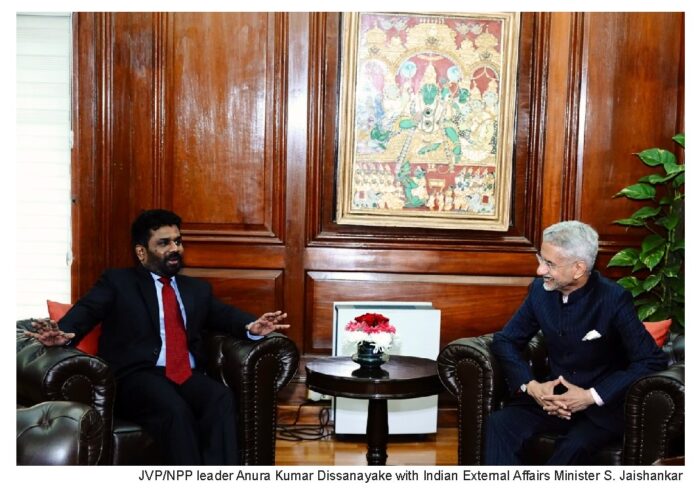

JVP leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s recent visit to India at the invitation of the Indian government has created quite a stir here. The JVP has said India’s invitation was for the NPP (National People’s Power) coalition, which it leads. In fact, the NPP is a mere political vehicle for the JVP, and India’s invitation was for the JVP for all practical purposes. Maybe, India addressed the invitation to the NPP, which has parliamentary representation.

Anti-Indianism has been a fundamental aspect of JVP’s ideology, and the second JVP uprising (1987-89) was basically against Indian intervention here. Having resisted ‘Indian expansionism’ and caused thousands of lives to be lost in the name of an armed struggle against it, the JVP and its leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD) find themselves in an unenviable position; they are trying to defend their policy about-turn.

Will AKD’s India visit be a kiss of death for the JVP/NPP? This is the question being asked in political circles.

The spin doctors of the JVP and its rivals are at war. They have got down and dirty. The Frontline Socialist Party (FSP), the UNP, the SJB, the SLPP, etc., are all out to cast the JVP in a bad light as a party that subjugates its policies to political expediency. They lost no time in bashing AKD, pointing out that one of the five classes the JVP used to conduct for new recruits was on the need to defeat India’s expansionist strategy.

The JVP is obviously reeling from its rivals’ criticism of its leader’s India visit. It has been taking great pains to counter adverse propaganda during the past several days. AKD himself appeared in an interview with Sirasa TV on Thursday night in a bid to defend himself and his party against their opponents’ propaganda onslaught.

AKD told Sirasa that he himself had attended the JVP’s five classes in 1987, but none of them was on Indian expansionism. He, however, admitted that the JVP had carried out an anti-Indian campaign in the late 1980s in retaliation for India’s hostile actions against Sri Lanka, such as the violation of the Sri Lankan airspace, the deployment of the Indian army here and pressure New Delhi brought to bear on President J. R. Jayewardene to sign the Indo-Lanka accord, which paved the way for the establishment of the Provincial Council system. He tried to justify what the JVP had done at that time, claiming that the situation the country was in due to the Indian interventionwarranted such action. AKD however sounded conciliatorywhen he talked about India’s concerns about its national security in the current context. The sobering geopolitical reality has apparently dawned on the JVP.

The JVP has been doing everything possible to put a positive spin on AKD’s India visit, and gain some political mileage at the same time. It would have the public believe that the Indian government extended an invitation to its leader because Indian is convinced that he will emerge the winner in the coming presidential race. It has also claimed that the world has begun to recognize the JVP, which had already received considerable regional recognition. It says its rivals are agitated because they never expected a regional power like India to recognize it; they thought only the political forces representing the interests of their class were in the good books of India and other powerful nations. Whether the majority of voters will buy into this claimand support the JVP remains to be seen.

The UNP propaganda mill went into overdrive the moment AKD and some other JVP seniors including Vijitha Herath left for India. It claimed that the Indian government’s invitation to them had been orchestrated by President Ranil Wickremesinghe as part of his strategy to facilitate the implementation of agreements between Sri Lanka and India. This argument helped the UNP put the JVP on the defensive. The JVP has since been striving to deny the government’s claim, and make its leader’s India visit out to be a foreign relations milestone.

What really matter is not the JVP’s claims about the U-turn in its foreign policy, in respect of India, or its rivals’ arguments about the issue, but public opinion which is influenced and shaped by many factors other than claims that a political party makes and counterclaims of its rivals.

The JVP, which was on the offensive, tearing into all its rivals, and projecting itself as the only political party whose policies had been consistent, is now on the back foot. This is something it may not have expected a few weeks ago. Politics is full of traps and tricks, and ups and downs like Snakes and Ladders. The JVP will have a hard time, trying to counter its rivals’ criticism of its U-turn on ‘Indian expansionism’, which it took up arms against in the late 1980s.

The presidential election is seven months away, and it is too early for the winner to be predicted. The Opposition says the government is planning to postpone the presidential election on the pretext of abolishing the executive presidency. The President’s Office has said the presidential election will be held on schedule.

The JVP is not likely to gain a boost from AKD’s India visit for its presidential election campaign, and its rivals may not be able to use the reconciliation between the JVP and India to turn public opinion against the JVP. Issues are cropping up at such a rate in this country that nobody will remember AKD’s visit to India in a few months or even weeks. But the government and the Opposition have made use of it to remind the public, especially the youth, of the JVP’s violent past, and the JVP has got an opportunity to try to reimage itself and gain some legitimacy.