The Indian Supreme Court on Tuesday refused to recognize the right of same-sex couples to enter into marriages or have civil unions [Supriyo @ Supriya Chakraborty and anr v. Union of India].

The Court said that the law as it stands today does not recognise the right to marry or the right of same-sex couples to enter into civil unions, and that it is upto the Parliament to make laws enabling the same.

The Court also held that the law does not recognise rights of same-sex couples to adopt children.

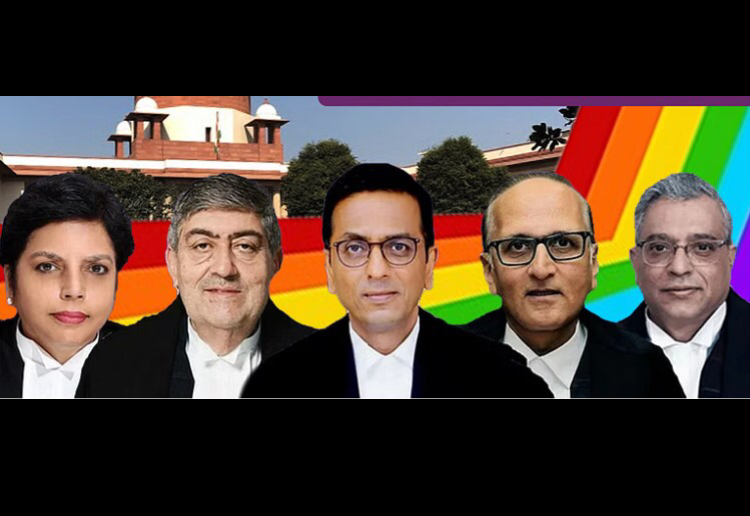

The judgment was rendered by a Constitution Bench of Chief Justice of India (CJI) DY Chandrachud and Justices Sanjay Kishan Kaul, S Ravindra Bhat, Hima Kohli and PS Narasimha. The Bench rendered four separate judgments.

The majority opinion was delivered by Justices Bhat, Kohli and Narasimha with Justice Narasimha delivering a separate concurring opinion. CJI Chandrachud and Justice Kaul delivered separate dissenting judgments.

All the judges were unanimous in holding that there is no unqualified right to marriage and same-sex couples cannot claim that as a fundamental right.

The Court also unanimously turned down the challenge to provisions of the Special Marriage Act.

The majority of Justices Bhat, Kohli and Narasimha also held that civil unions between same sex couples are not recognised under law and they cannot claim right to adopt children either.

However, CJI Chandrachud and Justice Kaul in their separate minority opinions ruled that same-sex couples are entitled to recognise their relationships as civil union and can claim consequential benefits.

In this regard, they also said that such couples have the right to adopt children and struck down adoption regulations to the extent it prevented the same.

CJI Chandrachud also said that provisions of Special Marriage Act cannot be struck down or words cannot be read into it to allow same-sex marriages.

Justice Kaul said that Special Marriage Act is discriminatory towards queer couples but concurred with the CJI in holding that it cannot be interpreted to allow same-sex marriages.

The majority opinion rendered by Justice Bhat held the following:

– There is no unqualified right to marriage.

– Entitlement to civil unions can be only through enacted laws and courts cannot enjoin such creation of a regulatory framework.

– Queer persons are not prohibited in celebrating their love for each other, but have no right to claim recognition of such union.

– Queer persons have the right to choose their own partner and they must be protected to enjoy such rights.

– Same-sex couples do not have right to adopt children under existing law.

– Central government shall set up a high-powered committee to undertake study of all relevant factors associated with same-sex marriage.

– Transgender persons have the right to marry.

The Court in its minority opinion held that queer couples have a right to enter into civil unions, though they do not have the right to marry under the existing laws.

The following are the highlights of CJI Chandrachud’s minority judgment:

– Queerness is not urban or elite.

– There is no universal concept of marriage. Marriage has attained the status of a legal institution due to regulations.

– The Constitution does not grant a fundamental right to marry and the institution cannot be elevated to the status of a fundamental right.

– The court cannot strike down provisions of the Special Marriage Act. It is for Parliament to decide the legal validity of same-sex marriage. Courts must steer clear of policy matters.

– Freedom of queer community to enter into unions is guaranteed under the Constitution. Denial of their rights is a denial of fundamental rights. The right to enter into unions cannot be based on sexual orientation.

– Transgender persons have the right to marry under existing law.

– Queer couples have the right to jointly adopt a child. Regulation 5(3) of the Adoption Regulations as framed by the Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA) is violative of Article 15 of the Constitution for discriminating against the queer community.

– Centre, states, union territories shall not bar queer people from entering into unions to avail benefits of the state.

The five-judge bench had reserved its verdict on May 11 this year, after a ten-day hearing. The Court was called upon to decide on a batch of pleas seeking legal recognition of same-sex marriages in India.

Among other developments during the course of the hearings, the Court noted that:

– The US Supreme Court’s decision that there was no Constitutional right to abortion was incorrect in the Indian context, and that an individual’s right to adopt was not affected by their marital status in India.

– Recognising same-sex unions was up to the Legislature, but the government may have to ensure that same-sex couples are given social and other benefits and legal rights without the label of marriage.

– Courts cannot decide on issues based on young people’s sentiments.

– Marriages are entitled to constitutional and not just statutory protections.

The lead petition was filed by Supriyo Chakraborty and Abhay Dang, two gay men living in Hyderabad.

Supriyo and Abhay have been a couple for almost 10 years. They both contracted COVID-19 during the second wave of the pandemic and when they recovered, they decided to have a wedding-cum-commitment ceremony to celebrate the ninth anniversary of their relationship.

However, despite the same, they do not enjoy the rights of a married couple, the plea pointed out.

It was also contended that the Supreme Court in the Puttaswamy case, held that LGBTQIA+ persons enjoy the right to equality, dignity and privacy guaranteed by the Constitution on the same footing as all other citizens.

The Central government opposed the petitions in Court, saying that same-sex couples living together as partners and having sexual relationships is not comparable to the Indian family unit concept, which involves a biological man and a biological woman with children born out of such wedlock.

The government also underlined that there can be no fundamental right for recognition of a particular form of social relationship.