-

How much does his opinion count in the inner-circle of government when political pygmies such as Wimal Weerawansa, Udaya Gammanpila and even Sudarshani Fernandopulle dare to defy him in public?

If politics is about marketing leaders to the masses, the leading brand and market leader in Sri Lanka is undoubtedly Mahinda Rajapaksa. The two-time President has his faults- of which there are many- but he is still the politician who wields the most clout in Sri Lanka. Why then is he being undermined, particularly from within his own camp?

Mahinda Rajapaksa, now nearly fifty-one years in politics and seventy-five years of age, went from President to ordinary citizen on the night of the eighth of January, 2015. Then, instead of retiring, he staged a remarkable comeback through a new political party and is now Prime Minister.

When Gotabaya Rajapaksa ran for President, it was only because Mahinda Rajapaksa couldn’t contest the election due to the 19th Amendment barring a third term for him. During the campaign, Mahinda was the dutiful elder brother, accompanying the people-shy Gotabaya to rallies. It was Mahinda who did the main speech; that was his forte. Gotabaya’s addresses were short, military style and didn’t send the public into raptures as it did when Mahinda asked ‘obata sathutuyida den?’ (‘Are you happy now?’).

Now though, Mahinda Rajapaksa’s pre-eminence is being questioned and a series of incidents point to a different centre of power emerging within the government, if not the ruling party, the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP).

The first stone was cast by that habitual sinner, Wimal Weerawansa. In an interview with a newspaper, Weerawansa said that Gotabaya Rajapaksa should be the leader of the SLPP, a position currently held by Mahinda Rajapaksa.

That generated a political storm. The general secretary of the SLPP, Sagara Kariyawasam called for an apology from Weerawansa saying that, not even being a member of the SLPP, Weerawansa should mind his own business, leaving the ruling party to make its own decisions.

There was no apology. Instead, Muruththetuwe Ananda, the influential monk who heads the nurses’ trade union went public, casting aspersions on Mahinda Rajapaksa’s ability to do the job. “He seems to have become lazy and lethargic,” he said in a television interview. It is worthwhile noting that it was this same monk who offered his temple, the Abhayaaramaya in Narahenpita to Mahinda Rajapaksa for his political work after his defeat in 2015.

Then came the controversy over Muslim burials. There was a cloud hanging over Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan’s trip to Sri Lanka because Imran is seen the world over as an ambassador for moderate Muslims and he couldn’t be seen visiting Sri Lanka, a country which appeared to be discriminating against his community by not allowing burials for Muslims who succumb to Covid-19. Khan was visiting Sri Lanka on the invitation of his Lankan counterpart, Mahinda Rajapaksa.

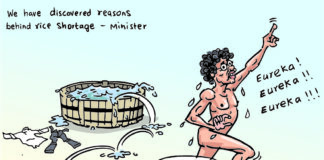

Ever the savvy politician, Mahinda Rajapaksa, responding to a question in Parliament said ‘we will allow burials for Muslims’. The words made international headlines, was described as a reversal of government policy and was duly picked up by Imran Khan who tweeted his approval.

That was two weeks ago. Nothing has happened since then because the gazette notification prohibiting burials for Covid-19 victims hasn’t been rescinded. The non-Cabinet Minister in charge of Covid-19, Dr. Sudarshani Fernandopulle, the widow of Mahinda’s good friend Jeyaraj, has told Parliament that burials can be allowed only if a technical committee approves it and that this is not a ‘personal decision’. There was also Minister Udaya Gammanpila saying Mahinda’s assurances were only his ‘personal opinion’.

Mahinda Rajapaksa has remained silent about this since then. The ban on burials meanwhile continues and has now become the focus of attention at sessions of the United Nations Human Rights Council sessions in Geneva.

Last but not least, there was the invitation extended by Mahinda Rajapaksa to Imran Khan to address the Sri Lankan Parliament. That too has been vetoed. The official reason, trotted out by Speaker Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena’s office is that Parliament cannot create a Covid-safe environment for the visiting leader. Of course, it is an open secret that this is not true.

Several reasons for the cancellation of Prime Minister Khan’s speech have been speculated upon. Some say Sri Lanka did not want to give parity to Khan with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi who also addressed Parliament. Others say it was feared the visiting Premier would seize the opportunity to comment on Kasmhir, angering India. There was also a suggestion that it was feared Khan would talk about the issue of burials for Muslims.

Whatever the real reason, Mahinda Rajapaksa’s invitation to Imran Khan to address Parliament was ignored, deferred, cancelled, postponed- depending on how you choose to look at it.

This brings us to the real question that underlies all this- Is Mahinda Rajapaksa not primus inter pares or first among equals anymore? How much does his opinion count in the inner-circle of government when political pygmies such as Wimal Weerawansa, Udaya Gammanpila and even Sudarshani Fernandopulle dare to defy him in public? Are they all echoing the sentiments of their Master, who is now vested with all executive powers? Is Mahinda’s star fading in the twilight of his political life, at the hands of his own kith and kin?

There is certainly a great deal of evidence to suggest that. Government has, unlike during Mahinda’s time, been through gazette’s and Generals. Retired military officers have been posted to key government departments in the guise of promoting productivity and efficiency and eliminating corruption, a laudable objective no doubt, but one that is yet to be realised.

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, after more than a year in the job, remains a distant, aloof figure. He is not the rambunctious type to mingle with the masses and guffaw with them. That was Mahinda’s niche. Gotabaya, when he attempted to do so in ‘Gama samaga pilisandarak’ (a conversation with the village), came a cropper: once he said that ‘what I say is the law’; on another occasion, he tried to ‘interview’ a lady who was seeking a position as an English teacher. He copped a tremendous backlash in both instances. Of course, Mahinda would have excelled in such situations.

Regardless of the inner machinations in government and despite all the flaws that he possesses, Mahinda Rajapaksa remains the best advertisement for the government. If he is relegated to the role of a ‘peon’, as Ranasinghe Premadasa once described his Premiership, the government is making an embarrassing and potentially fatal mistake: they are killing the goose that lays the golden egg.