The prime minister has turned India’s G-20 leadership into a nonstop advertisement for its growing clout.

By Manjari Chatterjee Miller, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, and Clare Harris, a research associate at the Council on Foreign Relations.

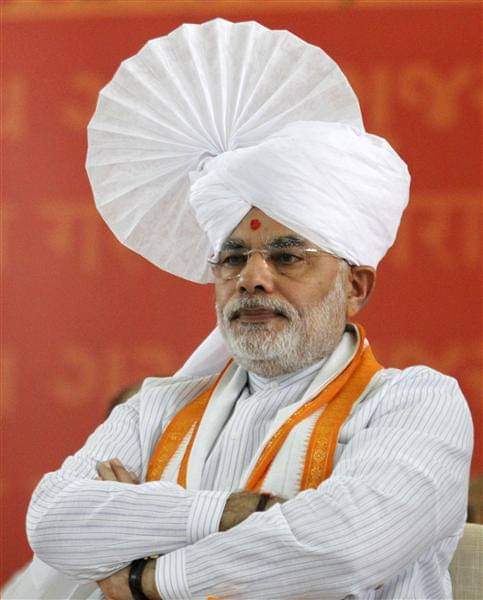

If you go almost anywhere in New Delhi, India’s capital, you won’t be far from a giant poster advertising its presidency of the G-20—a group of 19 large economies plus the European Union—alongside a portrait of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Switch on the TV or pick up a newspaper, and you’ll encounter gushing media coverage about how India’s term in charge of the group represents a moment for the country to showcase its global leadership. Recently, one of us received a mass email from a local research organization offering a training course on India’s G-20 presidency, with the promise of a formal certificate of completion.

The rotating G-20 presidency is usually symbolic: The presiding country hosts meetings and has the power to set the annual theme. Perhaps unsurprisingly, international media covering recent G-20 meetings have focused on the obvious tensions between member states. In March, a G-20 foreign ministers meeting in New Delhi made headlines when disagreements over the war in Ukraine came to the fore. But what the rest of the world seems to have ignored so far is how Modi is shrewdly marketing India’s presidency of the group to burnish his personal image and elevate his party.

By highlighting India’s position as a major power courted by countries including the United States, Modi and his supporters have boosted nationalist sentiments among the country’s masses. This is no small PR feat. The G-20 was meant to be a staid forum little known outside wonky circles; it is now trendy in India. This canny marketing has important ramifications for Modi’s chances to return to power in elections next year and for his stature on the global stage—but it is also not without risks. If, as India’s G-20 marketing seems to imply, Modi is responsible for the country’s increasing clout, then he could also shoulder the blame for a potential failure to deliver on global expectations.

When India assumed the G-20 presidency last December, there was an inkling that the Modi administration’s approach would be different to those of other recent group leaders. One hundred monuments around the country, including UNESCO world heritage sites, were illuminated for an entire week in celebration. Newspapers printed full-page ads to call attention to the start of India’s term. The Modi government rebranded the grouping a “People’s G-20.”

India plans to host more than 200 meetings in 56 cities during its leadership year. (Indonesia, as last year’s president, hosted meetings in just over 20 cities.) Along the way, New Delhi plans to highlight the country’s economic successes, including its advancements in solar power and digital health. The convenings will culminate in a summit in November, which commentators have already declared will be India’s “most prestigious diplomatic fete” since the Non-Aligned Movement summit in 1983.

New Delhi’s G-20 strategy includes an unusual level of public involvement, a fact highlighted in the government’s marketing campaign. State and local officials have organized a mass education campaign on India’s presidency, initiatives to encourage public participation, and school activities such as quizzes, essay-writing competitions, and debates. The government has asked universities to prepare students to act as local facilitators for foreign delegates in events and celebrations during the year. On one hand, this highly innovative strategy should be applauded. It democratizes an elitist summit, educates the public, and encourages them to understand foreign policymaking—typically the province of a tiny minority in most countries.

On the other hand, Modi’s goal isn’t just to further the G-20 among the Indian public but also to project himself as the only capable steward of a rising India. India’s G-20 strategy positions Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) as the vehicle for India’s presence on the global stage. This year’s logo replaces the zero in G-20 with the image of a globe inside a lotus, using the colours of the Indian flag. Although Modi’s administration has said the lotus stands for hope, it is also the symbol of the BJP—prominent on election ballots for any of the approximately 200 million Indian citizens who cannot read. Indian opposition leaders have issued repeated reminders that the G-20 leadership rotates and urged Modi not to frame the presidency as his personal achievement, but the BJP has so far ignored those calls. Ahead of the 2024 national elections, this positioning can help Modi further his claim to be the only person capable of bringing India’s major-power status to fruition.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Indonesian President Joko Widodo take part in the leadership handover ceremony during the G-20 summit in Bali, Indonesia, on Nov. 16.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Indonesian President Joko Widodo take part in the leadership handover ceremony during the G-20 summit in Bali, Indonesia, on Nov. 16.

India’s G-20 Presidency Is a Golden Opportunity

New Delhi has the chance to shape the global agenda and advocate for its vision of multilateralism.

This growing clout is accompanied by growing expectations of India—and by extension, of Modi. There is the tantalizing hope among India’s partners that India could leverage its nonaligned position and historic ties with Russia to negotiate diplomatic cooperation between Moscow and other G-20 capitals. Modi has also championed India’s role as a connector between the West and global south. In January, India hosted its Voice of the Global South summit, with delegates from 125 developing countries. But when Russia and China refused to sign a G-20 communique that mentioned the ongoing war in Ukraine, it dented the hope of India serving as a mediator between Moscow and Kyiv.

Beyond “[giving] resonance to the voice of the Global South,” an initiative that is not new but that India has championed for decades as one of the architects of the Non-Aligned Movement, New Delhi has not laid out the concrete deliverables of a global south grouping. For example, it is bringing the agenda of Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) to the G-20 table, but India—which has led in services rather than as a producer of technological goods—has yet to fully prove how it could offer DPI to global south countries. The facilitation of cross-border digital payments is one possibility: India just established a real-time payments linkage system with Singapore, where citizens of both countries can use India’s UPI and Singapore’s PayNow to directly send payments each way. Whether India can dramatically and rapidly expand this to other countries eager to establish such linkages remains to be seen.

Further complicating matters is the fact that China, which didn’t participate in India’s global south summit, also positions itself as a champion of non-Western countries and has stepped up its role beyond infrastructure development and financing. Its recent breakthrough diplomatic mediation between Saudi Arabia and Iran, with negotiations reportedly conducted only in Chinese, Persian, and Arabic to avoid leaks, came as an uneasy surprise to many.

The Modi government is being strategic and intentional about using the G-20 presidency to its advantage. By highlighting India’s heritage and economic successes as a rising world power, Modi aims to show that India can speak to the needs of smaller, developing nations as well as major world powers. Simultaneously, through aggressive advertising and by inviting the Indian public to be a part of this usually elite, remote, and even boring event, the government is making the case that India’s G-20 presidency and growing influence are a consequence of Modi’s strong leadership. The challenge for Modi lies in delivering on heightened expectations (.Foreign Policy Magazine)