It is time for Sri Lanka to take a hard look at the new dimension emerging in the international political theatre to shape and redesign its foreign policy.

Gone are the days that perpetuated nonaligned policies and the active role Sri Lanka played to reinvigorate the non-aligned movement with countries such as India and Yugoslavia.

Yugoslavia has itself disintegrated into several countries, and India has almost backed out of its Jawaharlal Nehru policies and drifted towards the United States of America while maintaining healthy relations with its former ally Russia.

At the same time, India has cultivated a very close relationship with Japan and Australia through the Quad – the quadrangle security arrangement concerning the Indo-Pacific region.

More than anything, the Indian economy has surpassed that of the United Kingdom (UK), the former colonial masters, in terms of GDP and economic growth.

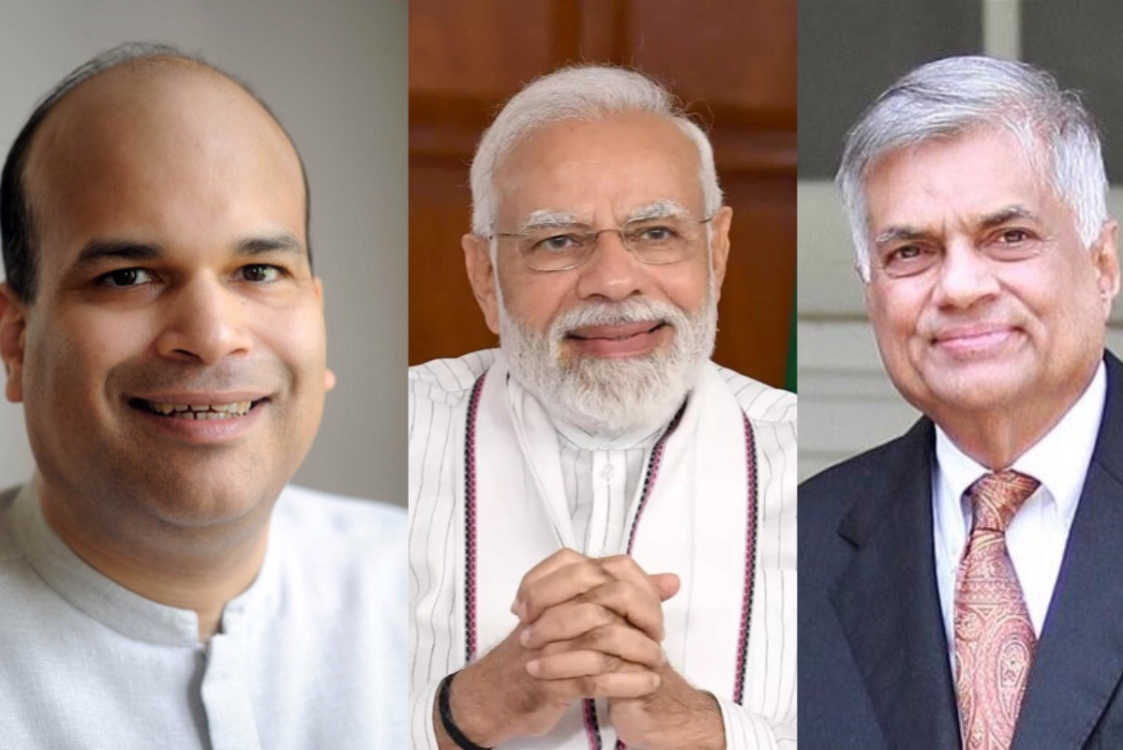

It is through the sheer dedication of their leaders that India has virtually displaced the UK from its etched position as the fifth largest economy in the world.

Indians were overwhelmed by the excellent progress they made in terms of economic indicators, while the Indian media allocated sizable space to talk about their achievements in terms of the economy.

All of this is critical for Sri Lanka to view India in a positive light and formulate its economic and foreign policies in line with the policies of her giant neighbour.

Can Sri Lanka think about economic emancipation without the Indian factor playing a dominant role?

Sri Lanka, being a small but important neighbour of India, should devise a formula to stabilise its relations with India that would benefit both countries in the long run.

In an article written for the New Indian Express, V Suryanarayan, formerly and a Senior Professor at the University of Madras’ Centre for South and Southeast Asian Studies, said, a country’s foreign policy is not static, it is subject to constant change, according to the needs of the changing world and the country’s requirements.

The personalities at the helm of government and their peculiar mindsets also shape the process of continuity and change. But all these have to work within the fundamental realities of the region. There is no way of getting away from the fact that India is looming large with its size, economic resources, military strength, and the big power-small power syndrome. It may be recalled that in the perception of the majority Sinhalese, J N Dixit, then Indian High Commissioner (in the post-1987 period), was viewed as the “Viceroy of India”. There are inherent fears and misgivings about India’s long-term intentions and capabilities. India, in turn, believes that its neighbour is getting close to China to “cut India to size”.

Adding complexity to the situation, the historical bonds of common cultural heritage and the spread of India’s ethno-cultural reach naturally raise fears of getting swamped. The overlap of a large number of ethno-religious-linguistic groups across India’s porous borders generates stresses and strains in bilateral relations by way of the movement of refugees, illegal migration, large-scale poaching by fishermen, and the spread of narcotics. I use the term Siamese twins to describe the close nexus between India and Sri Lanka. What afflicts one will affect the other.

Three guiding principles of India’s neighbourhood policy require reiteration. The ethnic tensions should not be solved by military means; New Delhi would adhere to asymmetric reciprocity in its relations with smaller neighbours; and the problems relating to ethnicity and nation-building could be solved not by the imposition of majoritarian rule but by participatory democracy. Sri Lanka has to work out a political system where a Tamil can be a proud Tamil while, at the same time, being a loyal Sri Lankan citizen.

Two illustrations bring out the legacy of mistrust, what I call the “love-hate syndrome.” In April 1971, faced with an internal revolt posed by the JVP, PM Sirimavo Bandaranaike requested Indian military assistance, which was spontaneously given. How did Sri Lanka reciprocate India’s goodwill? Six months later, when the East Pakistan crisis deteriorated and India had banned the overflight of Pakistani planes, Colombo permitted Pakistani Air Force planes to transit and provided refuelling facilities; the planes were meant for putting down the democratic aspirations of East Pakistanis.

The induction of the Indian Peace Keeping Force at the invitation of President Jayewardene, and the subsequent marginalisation of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), enabled the Sri Lankan armed forces to withdraw from the north and the east and tackle the problems posed by the second JVP revolt. In the natural course, it should have earned for India the gratitude of the Sinhalese; on the contrary, it was explained away as an illustration of India’s hegemonistic designs. What is more, the two antagonistic entities, the LTTE and the Sri Lankan armed forces, came together. Premadasa gave a “second life” to the LTTE by providing finance and arms.

This was part of the chequered Indo-Lanka relationship. With ups and downs, the two countries existed in a state of mutual distrust owing to many issues. Now it is time-appointed to do away with acrimonious political moves that will not augur well for both countries in the long run. Especially at a time when India is projecting itself as an emerging world power.

The stark reality is that Sri Lanka comes under a sheer compulsion to accept India as it is and adjust its (Sri Lankan) policies in a way that would not rub India the wrong way. At any cost, India doesn’t want its security compromised or tampered with, a justifiable claim in the ever-changing global arena.

It is also vital to improve relations if Sri Lanka is to forge ahead and achieve economic stability. As a country, it would be a mistake to go beyond bypassing India since India is privy to every minute move that Sri Lanka makes.

The arrival and docking of Yuan Wang 5, the Chinese survey and research vessel in Hambantota port, was a sore eye as far as India is concerned. The matter gave rise to many diplomatic issues and caused hiccups in the Indo-Lanka relations, with media hype to boot.

The expert opinion is that Sri Lanka should have exercised extreme caution when dealing with such delicate matters.

Amidst New Delhi’s disappointment over Colombo’s decision to have the Chinese tracking vessel docked in Hambantota, Sri Lanka’s High Commissioner for India called for building a new “framework” to deal with maritime security concerns in the future.

Speaking to The Hindu days after the Chinese ship, the Yuan Wang 5, departed from the Sri Lankan port, High Commissioner Milinda Moragoda said that Colombo had kept the Modi government briefed at the “highest levels” throughout the controversy.

The docking of the ship was an issue between Sri Lanka and India, according to High Commissioner Moragoda. The question is how to build a workable framework to avoid them in the future and prevent such instances from leading to a trust deficit.

‘Sri Lanka would like to build an equilibrium in the relationship where there are no surprises, despite the ups and downs’, said Moragoda.

High Commissioner Moragoda explained that China had obtained permission when Colombo was in the middle of severe political turmoil following the ouster of then President Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

However, according to official data, Yuan Wang 5’s visit came after at least ten research vessels of a different class docked in Colombo between 2019 and 2022 without causing any concern in New Delhi.

In other words, New Delhi did not raise any objection to them.

As it stands today, Sri Lanka has to create a new module through shuttle diplomacy outside normal channels, akin to what was in place during the latter part of the offensive against the LTTE.

It was first proposed by the Indian High Commissioner in Colombo, Alok Prasad, when he briefed the Sri Lankan authorities about India’s concerns about the final stage of the military campaign against the LTTE in the North.

India wanted to open a channel without going through the normal diplomatic channels, which would be cumbersome for the officials to communicate on sensitive issues without consulting the political leadership. It could have led to inordinate delays.

High Commissioner Alok Prasad’s suggestion went through then secretary to the President, Lalith Weeratunga, to which President Mahinda Rajapaksa had given the green light to set up teams from both sides who could have direct access to the political hierarchy.

President Rajapaksa nominated his senior advisors at the time, Basil Rajapaksa, Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa, and Secretary to the President Lalith Weeratunga, who could take decisions and respond to queries without going through arduous diplomatic channels.

The Indian government nominated M.K. Narayanan who was National Security Advisor, Shankar Menon, Foreign Secretary and Vijay Singh, Defence Secretary, as India’s team of officials.

Lalith Weeratunga who wrote about his experiences while working with the Indian team and how they maintained a friendly atmosphere throughout and stated thus:

‘Most of us holding key positions in President Rajapaksa’s government were very friendly with Alok Prasad and met for informal discussions very often. Many of these friendly chats were held at India House. In one of these casual meetings, I learnt later that Gotabhaya Rajapaksa had mentioned to Alok Prasad that an informal channel outside the foreign ministry would most likely facilitate the dialogue between the two governments and ease the tensions that cropped up from time to time. It is out of this discussion that the idea of the Troika emanated.

Much of the success attributed to the Troika was also because each person in the two teams had a direct link to their respective leadership. On our side, all three of us enjoyed the confidence of the President, but it is only natural that the duo, Basil and Gotabhaya, knew better what their brother’s thinking was on matters relating to relations with India.

Basil, the organiser in the Rajapaksa family, is known for poor public relations. But as head of the Troika, he delivered when it mattered.

I recollect the first meeting of the Troika that took place in Delhi at the Hyderabad House without any fanfare. The two sides understood very well that the purpose of this hitherto untried mechanism was to increase the level of understanding between the two officialdoms and also, had there been any misunderstandings due to communication issues, to iron them out. In my opinion, this initiative was more useful to Sri Lanka than to India because we were then in the thick of fighting the LTTE and it was crucial that India be fully aware of what the Sri Lankan government and its Armed Forces were doing. The personnel involved in the Troika could not only place facts with authenticity but could also take decisions on behalf of their respective governments. Had there been any issue arising out of these discussions, any member of either of the teams could have been on the phone to the leadership and obtained advice on further action.

At this first meeting, I vividly remember how the NSA of India clarified, with the minutest detail, why India needed to understand fully how we set about eliminating terrorism. Their responsibility towards the Tamils of Sri Lanka came out loud and clear. But that did not deter the Indian Troika from denouncing terrorism and pledging their fullest support to eliminate terrorism in Sri Lanka. On the other hand, for Sri Lanka, this initiative allowed us to lay bare the facts before those who mattered in the Indian policy-making apparatus; most often sensitive information doesn’t get across in its purest form when foreign ministries interact.

This is what is necessary for the present context to smoothen the rough edges of Indo-Lanka relations and maintain a healthy and balanced relationship that would enhance strategic relations. A better understanding between the neighbours will help create the much-desired equilibrium in the Indian Ocean region.

Nonetheless, it is critical to assess Indian concerns in a rapidly changing geopolitical environment, as well as carefully examine past experiences with India where we have failed.

In that sense, a broad discussion is essential to draw up a new mechanism that would eventually benefit both India and Sri Lanka and strengthen mutual trust as a close ally of India. The distrust and suspicion that cropped up at times will help Sri Lanka to make pragmatic and conciliatory moves as far as India is concerned.

The reality is that India is Sri Lanka’s closest neighbour, and China is distantly closer to Sri Lanka. Hence, for security, Sri Lanka should turn to India since there is no other way that Sri Lanka could make progress economically. Political stability and security are two main ingredients essential for the very existence of Sri Lanka. It is important that the leaders work towards this objective while maintaining friendly relations with China.

The country has a great opportunity to test the waters when the United Nations Human Rights Council sessions are scheduled for this month.