How would the late President J. R. Jayewardene feel if he knew his party’s frantic efforts to do away with the executive presidency he created and was so enamoured of? He would feel the same way as he did way back in the early 1970s, when his proposal for a powerful executive presidency met with stiff resistance from his own party, the UNP, which he bent to his will a couple of years later after taking over its leadership. He contemptuously rejected the idea of a President elected by Parliament; he wanted the people to elect their President directly.

We do not intend to discuss the whole gamut of issues pertaining to the executive presidency and the all-pervasive impact it has had on the county, or the merits and demerits of arguments for and against the moves being made to abolish it. Instead, we attempt to examine the rise of presidentialism vis-à-vis parliamentarianism, the transformation it has undergone over the years and the sea changes which the stances of the two main parties on the executive presidency have suffered besides the whys and wherefores of their actions.

UNP’s elephantine volte-face

Today, the UNP is all out to abrogate the 1978 Constitution, which it overwhelmingly voted for more than four decades ago, and reduce the presidency to a mere figurehead to be elected by Parliament. In other words, it is trying to turn JRJ on his head posthumously, so to speak! It is a supreme irony that those who are trying to scuttle the UNP’s efforts to abolish the executive presidency are the very ones who opposed that institution tooth and nail, calling it a threat to democracy, while the Presidents, representing the UNP, were in power.

In a half-baked democracy, where institutional safeguards to protect democracy are either absent or weak, absolute power, wielded by a leader with dictatorial tendencies, can be as destructive as a firearm in the hands of a trigger-happy desperado, This has been the experience of some African and Asian countries. Sri Lanka is no exception and, therefore, it is understandable why there has emerged so much of opposition to the executive presidency. Some of the opponents of this institution are genuinely desirous of safeguarding democracy while, for others, it is a case of sour grapes.

Some of the arguments for scrapping the executive presidency are compelling, but would we find ourselves in the Promised Land if efforts being made to abolish that institution reached fruition? Is the Westminster model flawless and will it help us protect democracy and restore Cabinet government?

UK: Primus inter pares a misnomer

Does the UK have a Cabinet government where the Prime Minister is only primus inter pares? More than five and a half decades ago, renowned political thinkers such as R. H. S. Crossman argued that the British PM had acquired what they called near presidential powers. They maintained that what Britain had was a presidential type of government and not a Cabinet government; though the doctrine of collective responsibility was maintained, some vital decisions were made unbeknownst to most Cabinet members. Crossman, therefore, concluded that the principle of collective responsibility had come to mean collective obedience of the whole administration to one person at the top. Harold Wilson was of the view that the prime ministerial government had given way to a ‘quasi-presidential prime ministerial autocracy. Graham Allen’s book, ‘The Last Prime Minister’ sheds more light on this transformation. In an advanced democracy like the UK, no leader is equal to the task of undermining the well-established systems and conventions, but that may not necessarily be the case elsewhere.

JRJ’s dream

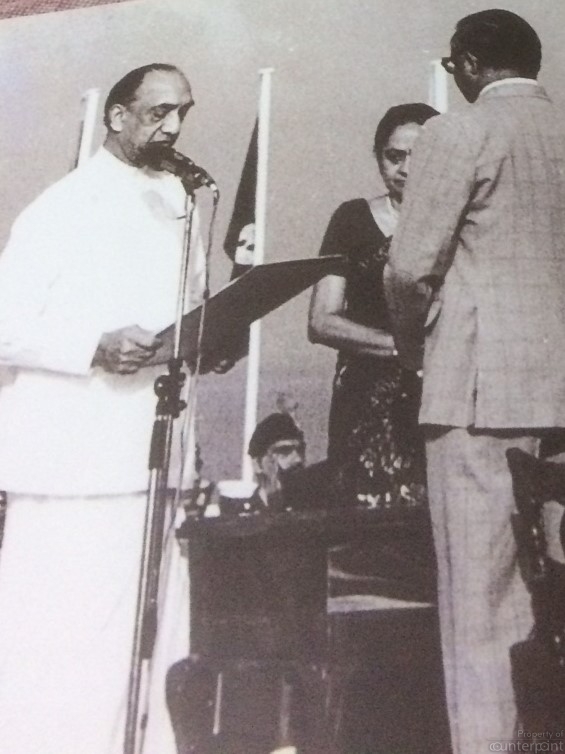

JRJ was apparently influenced by the transformation, the Westminster system was undergoing, and felt the need to overcome the weaknesses in the parliamentary system; he advocated a powerful executive for the country to face the developmental challenges, among other things. He used the 22nd session of the Ceylon Society for the Advancement of Science, in 1966, as a platform to launch his campaign, as it were, for an executive presidency.

Most criticisms against the executive presidency have gained wide acceptance owing to the manner in which the holders of it have misused or abused the enormous powers vested in it. During the tenures of JRJ and his successor, Ranasinghe Premadasa, critics such as Dr. N. M Perera and Dr. Colvin R. de Silva said Parliament had been reduced to a mere appendage of the executive presidency in that the President controlled the legislature through the Prime Minister and the Cabinet. Legal immunity enjoyed by the President became another issue.

The Cabinet was made subordinate to the President, who made all key appointments and had the power to remove ministers and even dissolve Parliament after the expiration of one year of the formation of a government. The President controlled all state institutions which became subservient to him. These criticisms were valid as regards President Chandrika Kumaratunga as well and the situation took a turn for the worse under the second term of President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who had more powers vested in the executive president and removed the term limit through the 18th Amendment to the Constitution.

President’s Achilles heel

The Executive Presidents become powerless vis-à-vis Prime Ministers when their parties lose control of Parliament. The late President D. B. Wijetunga was the first to experience this situation, in August 1994, when the SLFP-led People’s Alliance captured power in Parliament, but that did not lead to a crisis as such because Wijetunga was on his way out and Kumaratunga was elected President about three months later.

JRJ avoided such an eventuality by retaining his five-sixths majority in Parliament by conducting a referendum instead of a general election during his second term. The referendum was heavily rigged and democracy suffered heavily. The JVP used the resultant political turmoil to power its anarchical campaign and plunge the country into a bloodbath.

One of the main arguments against the executive presidency is that the holder of it tends to impose his or her will on the Cabinet and Parliament and run a one-man or one-woman show. This was one of the allegations in the impeachment motion against President Ranasinghe Premadasa, in 1991. JRJ, Kumaratunga and Rajapaksa acted likewise. JRJ once boasted that he could govern the country without both the Cabinet and the government. He, however, could not achieve that feat. Forty years on, such a situation arose in November 2018, when President Maithripala Sirisena managed the affairs of the State without both the Cabinet and the government, for a week or so, following an Appeal Court interim inunction, which prevented the then Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaska and ministers from functioning in their positions.

PM as de facto President

The country has also had Prime Ministers who acted as de facto presidents. Prof. A. J. Wilson, commenting on Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake’s style of governance, said the latter had acted more like a US President than a Prime Minister. That DS had a kitchen Cabinet, which took vital decisions is only too well known. Prime Minister Sirima Bandaranaike also dominated her Cabinets and parliamentary group. Her decision to join forces with Marxists in mid 1960s may serve as an example; she disregarded opposition from a section of her own party to her move. She emerged stronger between 1970 and 1977.

Prime Ministers, thereafter, became pliant under strong Presidents until 2001, when Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe placed himself on a collision course with President Kumaratunga, who lost control of Parliament. Prof. Wilson had anticipated a situation where the President would face a hostile Parliament. He thought that with the President thus cornered, the country would revert to prime ministerial government for all practical purposes. He expected the Executive President to submit himself/herself to the dictates of the Prime Minister. But Chandrika being Chandrika, nothing of the sort happened.

PM Wickremesinghe made inroads into what was considered the President’s province; he went so far as to sign a ceasefire agreement with the LTTE without informing the President or Parliament of his move in advance. The pact became a fait accompli. Wickremesinghe acted as the de facto President. President Kumaratunga fought back with might and main and took over the Ministry of Defence, following a Supreme Court determination that defence came under the purview of the President; she sacked the UNP-led UNF government afterwards and recaptured power in Parliament, at the 2004 general election.

President Sirisena recently declared in a televised speech that Prime Minister Wickremesinghe had exercised some of the presidential powers during the yahapalana government. It was the PM who ran the government, to all intents and purposes, from Jan. 2015 to Oct. 2018.

In the aftermath of what has come to be known as the Oct. 26 constitutional coup, Prime Minister Wickremesinghe confronted President Sirisena and succeeded in taming him eventually. The latter, who vowed not to reappoint the former the PM ever again, was made to eat his words. Never has an executive President been humiliated in this manner! The question is whether one can argue that the President is all powerful any longer.

The Opposition accuses Prime Minister Wickremesinghe of keeping his parliamentary group, the Cabinet, the Speaker and the Constitutional Council under his thumb. The 19th Amendment has strengthened the position of the PM, as never before, and put the Executive President in a constitutional straitjacket. It is only natural that the UNP wants the executive presidency abolished so that the PM can reign supreme.

Prime Minister Wickremesinghe’s trusted lieutenant, Minister Malik Samarawickrama, was quoted by the media as having said, last month, that the executive presidency did not strengthen the unitary status of the country or ensured political stability and, therefore, had to be scrapped. These views run counter to those JRJ expressed in favour of the executive presidency, which he later got the entire UNP to endorse.

The executive presidency JRJ created has lasted 40 years, but his party could hold it only for 17 years. The UNP has lost three presidential elections (in 1994, 1999 and 2005) and run away from two (in 2010 and 2015). Why the anti-UNP forces which once campaigned against the executive presidency have become well-disposed towards it is not surprising. Now, the UNP wants it abolished and favours the proposal for a president to be elected by Parliament, because it is not confident of winning the next presidential election.

The Old Fox, who created a government with a strong executive, which he did not want to be subject to the whims and fancies of an elected legislature, must be rolling over in his grave.

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...