The Khilafat misadventure was not without consequences. It had set a trend, both in the Congress as well as the League. For the League, it was more demands, and for the Congress, more capitulation.

Moplah Rebellion:

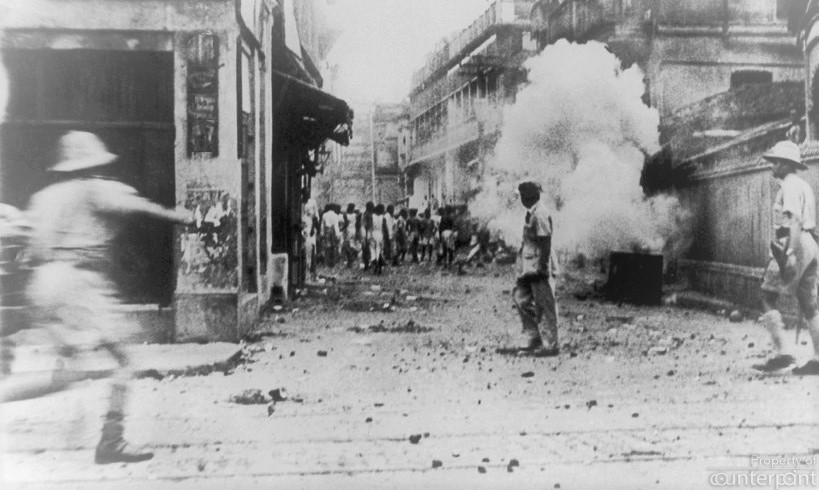

The Khilafat movement had led to massive violence in the Malabar Coast of Kerala when a local leader, Variankunnathu Kunjahammad Haji declared himself as the Khalifa and also designated two tehsils as ‘Khilafat Kingdoms’. He instigated his followers against the British. The rebellion, famously known as the Moplah Rebellion or the Malabar Rebellion, was launched on August 20, 1921, and continued for four months.

The Khilafat misadventure had set a trend, both in the Congress as well as the League. For the League, it was more demands, and for the Congress, more capitulation.

Taken aback initially by the unexpected aggression of the local Muslims called the Moplahs, the British returned with greater force and brutally suppressed the rebellion. All its leaders, including Haji were arrested. As the British were suppressing the rebellion, the Moplahs turned their ire against the local Hindus, blaming them for not fully supporting the Khilafat cause. Houses and temples were destroyed, women were dishonored, and people were forcefully converted or burnt alive. The atrocities committed by the Moplahs shook the conscience of many leaders, including Dr Ambedkar and Annie Besant. While Annie Besant vividly described the brutality against the Hindus, especially the women, Dr. Ambedkar minced no words in condemning the massacres by describing them as ‘blood-curdling’ and ‘indescribable’. Gandhi’s close confidant C. Rajagopalachari was so distraught by the cruelty of the Moplahs that he shot off a letter to Gandhi stating that “the atrocities of the Moplahs have made men, women, and children lose faith in the concept of Hindu-Muslim unity completely”.

When the AICC met at Ahmedabad in December 1921, the entire effort seemed directed towards downplaying the atrocities by the Moplahs. While the Servants of India Society led by Annie Besant reported that over twenty thousand Hindus were forcefully converted to Islam, the Congress claimed that as per their information, only three people were converted.

However, strange was the Congress reaction. When the AICC met at Ahmedabad in December 1921, the entire effort seemed directed towards downplaying the atrocities by the Moplahs. While the Servants of India Society led by Annie Besant reported that over twenty thousand Hindus were forcefully converted to Islam, the Congress claimed that as per their information, only three people were converted. The Ahmedabad session of Congress witnessed intense tussle between the Congress and League members over the Moplah incidents. All that could be said in the resolution was that the Congress “…is of the opinion that the…disturbance in Malabar could have been prevented by the Government of Madras accepting the proffered assistance of Maulana Yakub Hassan”.

Describing the events at the session, Swami Shraddhanand, a senior leader, wrote: “The original resolution condemned the Moplas wholesale for the killing of Hindus and burning of Hindu homes and the forcible conversion to Islam. The Hindu members themselves proposed amendments until it was reduced to condemning only certain individuals who had been guilty of the above crimes. But some of the Muslim leaders could not bear this even. Maulana Fakir and other Maulanas, of course, opposed the resolution, and there was no wonder. Nevertheless, it was most surprising that an out-and-out Nationalist like Maulana Hasrat Mohani opposed the resolution on the ground that — the Mopla country no longer remained Dar-ul-Aman but became Dar-ul-Harab and they suspected the Hindus of collusion with the British enemies of the Moplas. Therefore, the Moplas were right in presenting the Quran or sword to the Hindus. Moreover, if the Hindus became Mussalmans to save themselves from death, it was a voluntary change of faith and not forcible conversion—Well, even the harmless resolution condemning some of the Moplas was not unanimously passed but had to be accepted by a majority of votes only”.

All this for the sake of keeping the League as a bed-fellow. When Gandhi too downplayed the incident by commenting that the Moplahs were ‘brave and God-fearing, and were fighting for what they considered as religion, in a manner which they consider as religious,’ even Dr Ambedkar could not help but express his despair. He decried saying ‘Mr. Gandhi was so much obsessed by the necessity of establishing Hindu-Muslim unity that he was prepared to make light of the doings of the Moplas and the Khilafats.’

Vande Mataram:

After the Khilafat and the Moplah rebellion, the Muslim League started insisting on rejecting the essential symbols of national unity as a price for its support to the Congress.

After the Khilafat and the Moplah rebellion, the Muslim League’s price went up further. It started insisting on rejecting the essential symbols of national unity as a price for its support to the Congress. The first to come in the League’s crosshairs was the song Vande Mataram. It became a regular practice since 1905 to sing it at all the important Congress events. But the League members in the Congress started raising objections to it.

The AICC sessions were held in Kakinada in Andhra Pradesh in 1923. Maulana Mohammad Ali was presiding over the Congress. Senior leaders, including Motilal Nehru, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Sarojini Naidu, Sardar Patel, and Kasturba Gandhi, were present along with over twelve thousand delegates. Gandhi was in prison and hence could not attend.

Like in the past, Pt. Vishnu Digambar Puluskar, a Hindustani musician from Maharashtra, was there to sing the song at the inaugural. When Pt. Puluskar climbed the dais to sing Vande Mataram, Mohammad Ali raised objection saying that singing the song would hurt the sentiments of religious Muslims. Seeing the silence of the leaders present on the dais, Puluskar took it upon himself to challenge Mohammad Ali and went ahead with its rendition. Mohammad Ali, in protest, walked away while the song was being sung. It may be worthwhile to mention here that on many earlier occasions, the Ali Brothers and other League leaders used to rise together with other Hindu and Muslim members of the Congress when the song was sung. The objection at the Kakinada session was thus more a part of the enhanced bargaining than a genuinely religious issue. To placate the League members, Congress introduced Mohammad Iqbal’s famous song ‘Saare jahan se Acchha – Hindustan Hamara’ in its sessions. Yet, the opposition to Vande Mataram continued.

In 1937, when the elections were held for the Provincial Councils, the Congress formed governments in several of them. The controversy over Vande Mataram was raised once again when the proposal to sing the song at the commencement of the sessions was opposed. A ‘committee’ had to be constituted to reviewVande Mataram. Rabindranath Tagore, Subhash Chandra Bose, and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru were made its members. The committee recommended that the song be truncated and only the first two stanzas be sung.

The national song was partitioned in 1937 to appease the Muslim League. Ten years later, the nation was partitioned.

(To continue)

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...