The current Sri Lankan government that was elected in November 2019 has faced numerous challenges since Gotabaya Rajapaksa was elected executive president.

The problems were so severe that he was forced to flee under coercion and duress.

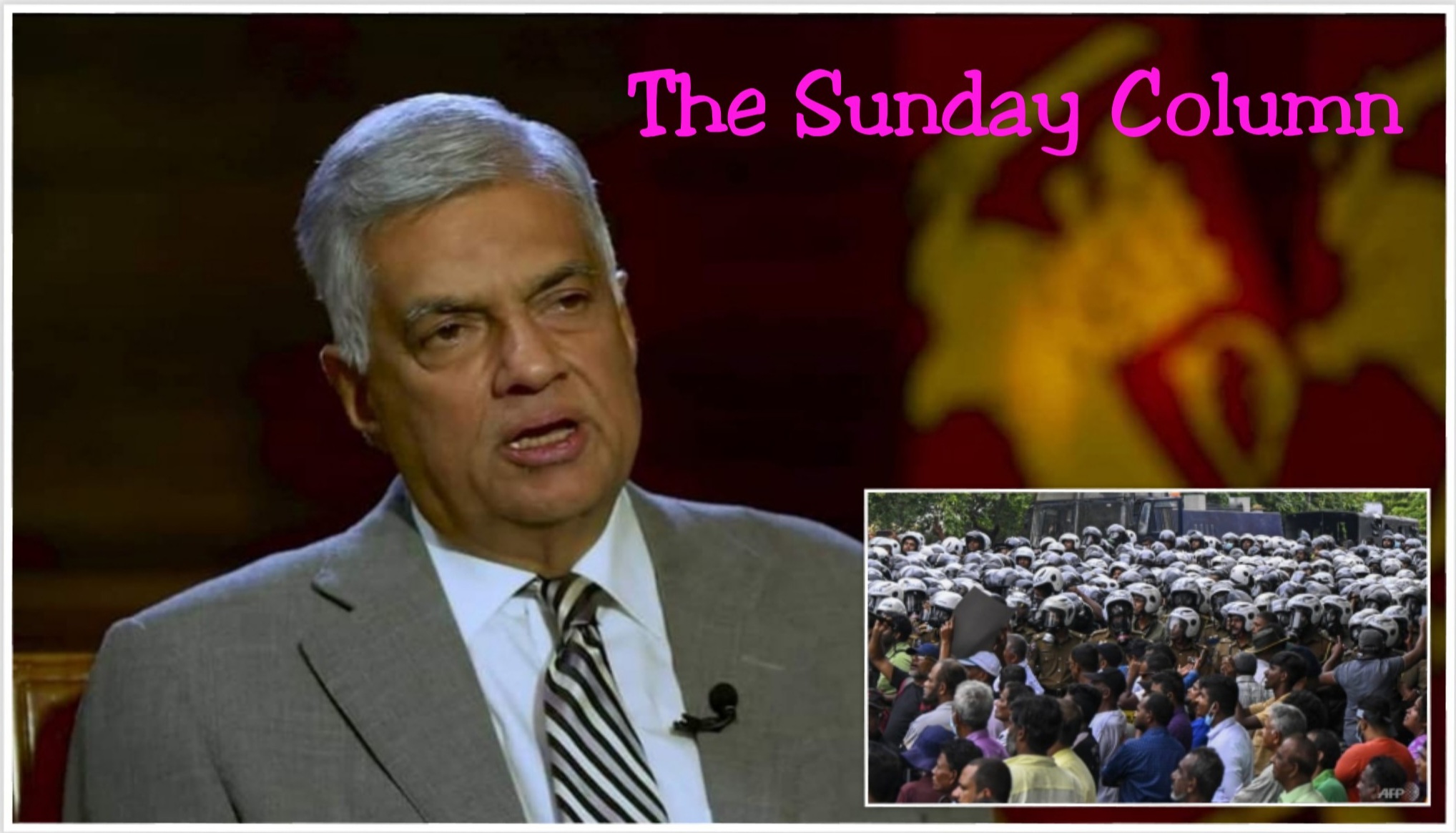

He made a series of blunders which pushed him out of high office. Though police brutality was not counted as one of his blatant mistakes, it has now come to the forefront under Ranil Wickremesinghe’s stewardship which is only an extension of the Gotabaya Rajapaksa regime.

What the police don’t realise is that implementation of the law to the letter of the law is one thing. Doing so with brutal force and ruthless cruelty is quite another. Using brutal force is diametrically opposed to the very objectives of policing and all the given norms of a democratic society.

Protest and protest marches are legitimate instruments in the armoury of any political party, Trade Union, student unions or similar organisations that are as powerful as their slogans. They educate the people about what a government in power is reluctant to tell the masses what they are trying to do.

Journalists or scribes are a fraternity that devote themselves to going anywhere or to any front as part of their obligation to inform people and duty. This is despite the occupational hazards they may face in their profession. A journalist getting beaten up by the police during a protest march is a serious omission on the part of the police since they have virtually obstructed him or her from performing essential duties.

The case of Tharindu Uduwaragedara is a similar case where the police deliberately targeted a journalist who is critical of the role played by the police. They tortured him during a protest march in Colombo and while he was seated inside a three-wheeler. Uduwaragedara incidentally, was a visible figure during last year’s Aragalaya. The attack on him smacks of the continuing witch hunt of Aragalaya activists.

All law-abiding people have condemned this reprehensible act in no uncertain terms calling on the police to restrain and not take illegal orders from their political masters.

As Amnesty International puts it under the title Police Violence, it states:

‘At its most extreme, unlawful use of force by police can deprive people of their right to life. If the police force is unnecessary or excessive, it may also amount to torture or other ill-treatment.

An unlawful police force can also violate the right to be free from discrimination. It can also violate the right to liberty and security, and the right to equal protection under the law’.

International laws and standards govern how and when police can use force – particularly lethal force.

The UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials (BPUFF) is the key international instrument dealing with police use of force.

The most important thing to remember is this: it is the utmost obligation of state authorities, including police, to respect and protect the right to life.

Under international law, police officers should only use lethal force as a last resort. This means when such force is strictly necessary to protect themselves or others from the imminent threat of death or serious injury. This is only used when other de-escalation options are insufficient.

Tharindu Uduwaragedara who was produced in court the following day was released on bail since the police could not explain why he should be kept in judicial custody.

Uduwaragedara is planning to file a Fundamental Rights petition before the Supreme Court to request the court to inquire into the matter. A matter that could be of importance to the entire country regarding police brutality.

Meanwhile, the Human Rights Commission will proceed with a separate case to unravel the truth and question each and every policeman involved in the case. As it stands today the legal fraternity and the police are at loggerheads owing to various reasons that stem from the Argalaya which culminated in Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s resignation from high office.

Sri Lanka has also been plagued with issues pertaining to health. Once the model health system in South Asia, the position has dwindled below expected standards, largely due to poor policy making and governance in the health sector. The country now has a high rate of mental health issues, a large population of undernourished citizens, and increasing rates of non-communicable diseases. Furthermore, access to quality health services is becoming increasingly difficult for those living in rural areas.

The recent incident where a child died following the removal of both his kidneys by a paediatric surgeon has shocked Sri Lankan society as to how it was possible for a trained surgeon to make such a blunder. The three-year-old boy from Kotahena had developed a chronic disease requiring the surgeon to remove the faulty kidney. However, the parents claim that during the surgical procedure the doctor removed the properly functioning kidney too. The boy, without both kidneys by now, went through haemodialysis until a suitable kidney was found for transplant surgery. The boy later contracted an infection which eventually brought about his demise. The surgeon, who is attached to the Colombo medical faculty, has already left the country, but several parties contemplate legal action. The Government Medical Officers Association has called on all parties to the problem to hold a proper inquiry before drawing conclusions.

Negligence on the part of medical professionals has become rampant and a serious issue that Sri Lankan society has to bear. This is until such laws concerning medical negligence are enacted and in place.

Alas, there are no proper criteria laid down by Sri Lanka’s Tort law to deal with such situations. A tort is an act or omission which results in injury or harm to another and amounts to a civil wrong for which courts impose liability. Therefore, it is necessary to have comprehensive laws enacted against professional misconduct not only by medical professionals but also by others.

However, weaknesses and ambiguities in the present legal regime delay such cases through prolonged litigation.

It also involves the examination of the legal principles followed by the courts in assessing the quantum of damages. There could also be practical difficulties within the current legal system in Sri Lanka. In the Sri Lankan healthcare field, it is essential to reduce the high incidence of malpractice which manifestly contribute to negligence. The shortage of trained healthcare professionals with expertise in the public and private sectors has ostensibly contributed to this since less skilled substitutes would undertake more complex tasks. Assessing damages in such cases is fraught with difficulty. It would be difficult for a court of law to weigh the strength of the law and the available evidence depending on the circumstances.

The only case that created public interest was the case cited in law reports as President’s Counsel Rienze Arsacularatne Vs Professor Priyani Soysa. The relevant question was the degree of professional care and attention prescribed by Sri Lanka’s administration of justice system.

Suhani Arsecularatne the four-year-old daughter of Rienzie Arsecularatne had been taken for treatment to Professor Soysa on the 18th of May 1992. On her advice, the child was admitted to the Nawaloka Hospital and treated for almost one month. As her condition deteriorated, her father, a President’s Counsel, switched doctors, but all efforts were futile. The child died a month later.

The matter came up before the courts of law for adjudication. The judge listened to both sides and then rendered a decision. The ruling determined who was responsible for the damages caused. The aggrieved party was then awarded a monetary settlement as a result.

PC Arsecularatne’s argument was that lapses on Professor Soysa’s part in treating the child who had been committed to her care directly, resulted in her death. Professor Soysa in turn countered that she had not been negligent in her diagnosis. She had not deviated from standard and accepted medical practices when examining the child.

The opinion of Colombo District Judge Mahanama Tillekeratne, before whom the matter first came, is worth mentioning. The Judge held that Professor Soysa was palpably negligent. More so, her “arrogance, indifference and intolerance”, was described by the District Judge in sturdy language in no uncertain terms, as figured clearly in the evidence. She was alleged to have made a serious misdiagnosis, which could have been prevented if she had shown the child more care and attention. the District Court held.

Professor Soysa appealed against this judgement, citing several grounds and claiming that the District Court erred in its decision. Her contention was that she had not been judged fairly and according to accepted medical norms. For this, she cited evidence from experts such as Dr J.B. Peiris, Professor Lamabadusuriya, Professor Harendra de Silva and Dr Shelton Cabraal. These experts testified on her behalf during the trial.

Their evidence clearly showed that she had not been negligent. She also argued that the District Judge had failed to approach the case with the necessary degree of objectivity and detachment. He had shown obvious sympathy for Arsecularatne while she had been treated callous disregard by him. His displeasure manifested in her professional conduct and certain characteristics of her personality as inferred by him.

During the proceedings in the Court of Appeal, both judges of the Court, Justices Weerasekera and Wigneswaran agreed with the finding of the District Judge, that Professor Soysa had been negligent. Justice Wigneswaran has explained his reasons for affirming this finding in a 151-page judgement. This focuses on what is said to have been certain crucial professional lapses on the part of Professor Priyani Soysa.

Nevertheless, her appeal to the Supreme Court brought her relief when a bench comprising three Supreme Court judges presided over by Justice Ranjith Dheeraratne allowed the appeal.

The case of Baby Hamdi too would be a test case if contested by the parents with the doctors. It is doubtful whether the parents could maintain their case without some social movement.

It is imperative for organisations of patients’ rights to urge the government to come up with clear legislation to deal with such unfortunate situations. This will further strengthen the Sri Lankan legal system.

On the political front the main gossip centres around the next presidential election and that it would be possible either in July or August next year. It is obvious that the incumbent President may contest, taking an independent view of the current situation. He may not be the UNP candidate as expected but may be a common candidate of a broader alliance. The President may also bring in legislation for the full implementation of the 13th amendment but sans police powers, which will be to the chagrin of Tamil political parties. They meanwhile, are not ready to budge from their declared position of a federal state and meaningful devolution. This is if the government is willing to resolve the ethnic question once and for all.

It is now very clear that President Wickremesinghe is no longer the liberal democrat that he pretended to be when he was Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition. He sheds all that to show off a contrived character more aligned with the SLPP’s thinking to grab a slice of their vote bank if any at the next Presidential election scheduled for next year.

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...