The Sri Lanka Parliament is set to elect a new President tomorrow (20) amidst a political turmoil owing to the resignation of President Rajapaksa. This is the second time such an election is taking place in the House. The parliament elected an interim President for the first time in May 1993, following the assassination of President Ranasinghe Premadasa. The transition was smooth. The then Prime Minister D. B. Wijetunga took over as the President, and a few days later, the parliament elected him uncontested. But this time around, there is a contest.

Nominations for the post of the interim President are being accepted by the Secretary General of Parliament at the time of writing, and horse-trading has been going on for the past several days. The SLPP government is likely to do whatever it takes to retain power.

There are now only two front-runners—Acting President Ranil Wickremesinghe and former Minister Dullas Alahapperuma; Opposition Leader Sajith Premadasa pulled out of the race, yesterday, in favour of Alahapperuma. The SLPP is divided over tomorrow’s vote with its General Secretary Sagara Kariyawasam having decided to support Wickremesinghe, and SLPP President Prof. G. L. Peiris contradicting him and offering the party’s support to SLPP dissident Alahapperuma. Other political parties are expected to announce their positions today.

Premadasa and Alahapperuma met last night to negotiate a pact, and reached a consensus. A section of the SJB urged Premadasa to pull out of the contest, support Alahpperuma and accept the post of the Prime Minister. He heeded their advice.

Leader of the JVP-led NPP Anura Kumara Dissanayake has also said he will also contest tomorrow, but added in the same breath that he will withdraw from the race if a candidate acceptable to all stakeholders is fielded.

Gota, the go-getter

Gotabaya’s meteoric rise in politics was remarkable, and his fall unprecedented. What really led to Gota’s resignation? Politics is full of glorious uncertainties. Whoever would have thought, in Nov. 2019, that President Rajapaksa, backed by 6.9 million voters, would have to resign before completing three years of his term? He earned a name for himself as a tough combat officer of the Sri Lanka Army, and thereafter as no-nonsense bureaucrat with the tenacity of a bulldog. When he was the Secretary of Defence and Urban Development, he relentlessly pursued his goals and achieved success.

Gotabaya made a tremendous contribution to the country’s war victory against the LTTE. He ran the Defence Ministry with an iron fist, and it was his way or highway for anyone except the then President Mahinda Rajapaksa. Even the tough service commanders fell in line at meetings chaired by him. Such was the strength of his character.

When Gotabaya introduced the current seatbelt law, not many took it seriously. It was thought that the police would take the new law for granted, but today nobody dares drive, or be driven, in the shotgun seat without a seatbelt on. Gota also endeared himself to the middle-class Sri Lankans through his urban development projects, especially recreational parks complete with modern jogging tracks. He did not hesitate to bulldoze his way through when there emerged resistance to his urban gentrification projects. Illegal constructions were pulled down overnight despite protests, and most urban centres were beautified and equipped with modern facilities. State-owned tumbledown edifices in Colombo were transformed into posh shopping malls. He was instrumental in ridding Colombo and other urban centres of garbage, a task that successive governments had failed to accomplish for decades.

Gota’s fetish for discipline, hard work, organization, cleanliness, and results, and his businesslike approach to everything in life helped him stand head and shoulders above the others when the need arose for the SLPP to nominate someone for the presidential election (2019). The Easter Sunday terrorist bombings had catapulted national security back to the centerstage of politics, and the yahapalana government had made a mess of almost everything, and created a situation, where the people looked for a strong leader capable of meeting the challenges the country was faced with, on all fronts. Out of their desperation they saw a messiah in Gotabaya.

The Family

Gotabaya started planning his presidential election campaign immediately after the 2015 regime change. He began building his image, and rallied the support of intellectuals, some of whom banded together as Viyathmaga, which held a series of seminars and promoted Gotabaya as a national leader. Prominent businessmen also rallied behind him, and he was not short of funds for electioneering.

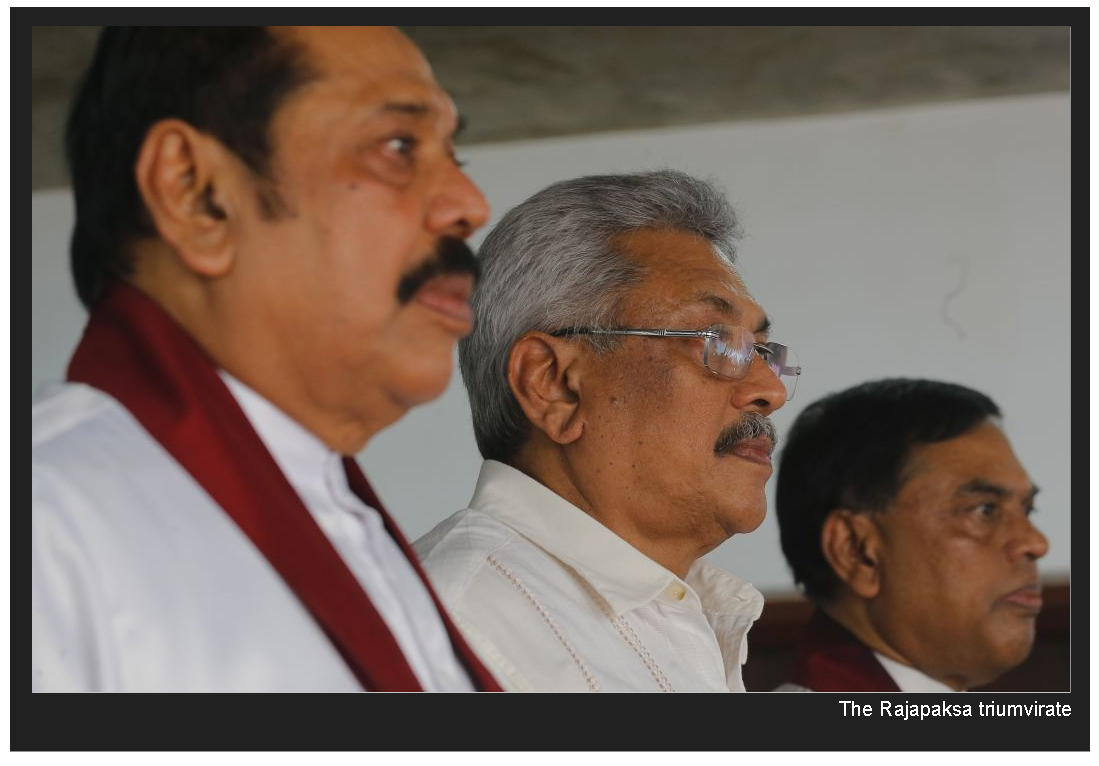

However, Gotabaya would not have been able to win the presidency under his own steam however capable the people may have thought him to be. Former President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s popularity and political acumen, and former Minister Basil Rajapaksa’s organizational skills stood Gotabaya in good stead. Thus, his family became an asset to Gotabaya ahead of the presidential election and the parliamentary polls in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

Paradoxically, his family also became a liability for Gotabaya after being ensconced in power. He was not free from family pressure in everything he did. He had to appoint all his family members and relatives in the parliament, save one, as ministers; Mahinda became the Prime Minister. The Rajapaksas had the lion’s share of budgetary allocations much to the resentment of other ministers.

Gota’s Achilles’ heel

The strength of any Executive President in Sri Lanka is derived from his or her control over the ruling party. When the President and the Prime Minister happen to represent two different parties, the latter becomes more powerful than the former to all intents and purposes. From 2001 to 2004, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe acted as the de facto President because the then President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s party, the People’s Alliance, lost the 2001 general election, and the UNP-led United Front wrested control of the parliament. We witnessed something similar from 2015 to 2019, when President Maithripala Sirisena was undermined by Prime Minister Wickremesinghe, whose party, the UNP, controlled the parliament.

In the case of Gotabaya, he represented the same party as the PM—the SLPP. But he was not the party leader. The person elected President automatically becomes the leader of either the UNP or the SLFP, but that is not so in respect of the SLPP. It was thought that since the Rajapaksas were a united family, the President would be able to exercise control over the SLPP. But in power politics, blood is not thicker than water. The history of this country is full of instances of family feuds over the throne, and such power struggles among ancient rulers even led to parricide. In post-Independence Sri Lanka, the Bandaranaike family fell apart as its members fought among themselves for power, and Anura Bandaranaike even took her mother, Sirimavo, to courts over a party dispute. There was no such bitter power struggle in the Rajapaksa family, but Gotabaya could not have his own way with the SLPP, which is Basil’s turf.

Political power turns group dynamics on their head regardless of whether it is exercised by family members or non-related players. Three camps emerged in the SLPP around Gotabaya, Mahinda and Basil. Mahinda chose to maintain a low profile, letting his siblings run the government. He apparently evinced a keen interest only in fortifying his eldest son, Namal’s political future. The Basil group became dominant in the SLPP by virtue of having control over the party’s parliamentary group. The old timers who were close to the Mahinda felt marginalized and sought to assert themselves only to be short-changed by both Gotabaya and Basil, and, in the end, they rebelled against the SLPP leadership and broke ranks.

His inability to control the ruling party became Gota’s Achilles’ heel. The SLPP dissidents such as Wimal Weerawansa and Udaya Gammanpila read the situation accurately very early, and predicted what was in store for Gotabaya. Hence their campaign to have him made the SLPP leader. Their abortive efforts to achieve that goal and criticism of the SLPP leadership resulted in their removal from the Cabinet.

Trouble begins for Gota

Public opinion began to turn against Gotabaya thanks to his disastrous green agriculture experiment which was carried out at the behest of some of his advisors who are far removed from reality. He imposed a blanket ban on agrochemicals overnight. He did in a hurry what should have been done over a period of time. The country’s shift to organic agriculture should have been done gradually. Even those who heaped praise on the President for the ban in question, and egged him on are now critical of his organic fertilizer policy! Farmers were the first to turn against the Gotabaya government. Unable to bear the yield losses due to the non-availability of chemical fertilizer, they rebelled, burning as they did the effigies of the President and Agriculture Minister Mahindananda Aluthgamage. Protests tend to snowball, and farmers’ agitations pave the way for mass agitations a few months later.

Gotabaya surrounded himself with the wrong advisors, especially a bunch of economists who were well past the retirement age. He failed to manage the country’s foreign reserves which were dwindling because they could not be replenished due to the economic fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic. Remittances from expatriate Sri Lankan workers, and earnings from tourism dried up with pandemic related expenditure increasing. But the foreign currency crisis could have been resolved if IMF assistance had been sought early before the reserves fell below 2 billion US dollars. Instead, Gotabaya allowed his economists to defend the rupee against the US dollar at the expense of the foreign exchange, totally disregarding the advice of the Central Bank.

Mahinda steered the country out of a similar crisis in 2009 with the help of the IMF under the guidance of the Central Bank, when he was the President, and Gotabaya should have consulted him. Money printing also increased exponentially, causing inflation to soar and the rupee to depreciate rapidly. The end result was that the country ran out of foreign currency reserves and had to default on its external debt thus causing its credit ratings to plummet and making it extremely difficult to secure IMF assistance due to time-consuming processes such as debt restructuring.

Wrong advisors and manipulations

The dollar crisis brought about shortages of all sorts. When the current year dawned, there was no need for the Opposition to take the people to the streets against the government; they were already there in the streets, waiting in queues for LP gas and milk powder. Then the shortage of petrol, diesel and kerosene manifested itself causing many more queues around the country, and affecting all sectors badly. Public anger built up and poured onto the streets with the anti-government forces tapping it effectively to power their political projects. People gathered opposite Gotabaya’s private residence at Mirihana on March 31 and held a protest against the fuel shortage and high cost of living, triggering a wave of agitations countrywide. Protesters set up a permanent base near the Presidential Secretariat.

Gotabaya also promised a clean government during his presidential election campaign. But a mega scam tarnished the image of his administration at the very inception. Duty on sugar was waived for the benefit of a key financier of the SLPP, and the state coffers suffered a massive loss. There was no end to allegations of bribery and corruption against the members of his Cabinet except a few.

Gotabaya could have retained the presidency if he had responded to the calls from religious leaders, SLPP dissidents, the media, trade unions, business leaders and various others to form a truly all-party interim government to tackle the present crisis and conduct a general election next year. Instead, he in his wisdom appointed Ranil Wickremesinghe the Prime Minister when Opposition Leader Premadasa rejected the offer of premiership. He could have saved his skin even if he had formed an all-party government on the eve of the 09 July uprising. If he had done so, he would have been able to defuse tensions in the polity and prevent the people from invading the President’s House. Insiders say he was amenable to the idea of an all-party administration, but the SLPP was not agreeable because such a power-sharing arrangement would have left no room for the Rajapaksa family to call the shots in the government. So, Gota had to leave the country and send his resignation letter from Singapore on 14 July.

Gotabaya finds himself in the current predicament because he did not realize that Sri Lankan politics was a different ball game, where one has to be as chaotic as the system to stay afloat. He may have expected to run the government the way he had managed the Defence Ministry and the Urban Development Authority. He did not care to listen to dissenting views, much less take them on board. He allowed the members of his inner circle to build a wall around him; he became a prisoner of both his advisors and the SLPP. He also chose to bite off more than he could chew, the green agriculture project being the best example, and made numerous U-turns as a result, making the public wonder whether they could trust him any longer as a strong leader. He asked for trouble and had it, and the country is in an unholy mess.

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...