A weekly paper said on Sunday that the government is to revive an earlier proposal to set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Sri Lanka (TRCSL) to address the long-standing issues of rights violations, alleged war crimes and ethnic reconciliation. On the face of it, the proposal is reasonable.

But there is serious doubt if a TRC will meet its objectives. The reasons are partly rooted in ground realities and partly in the failure of its model – the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (TRCSA).

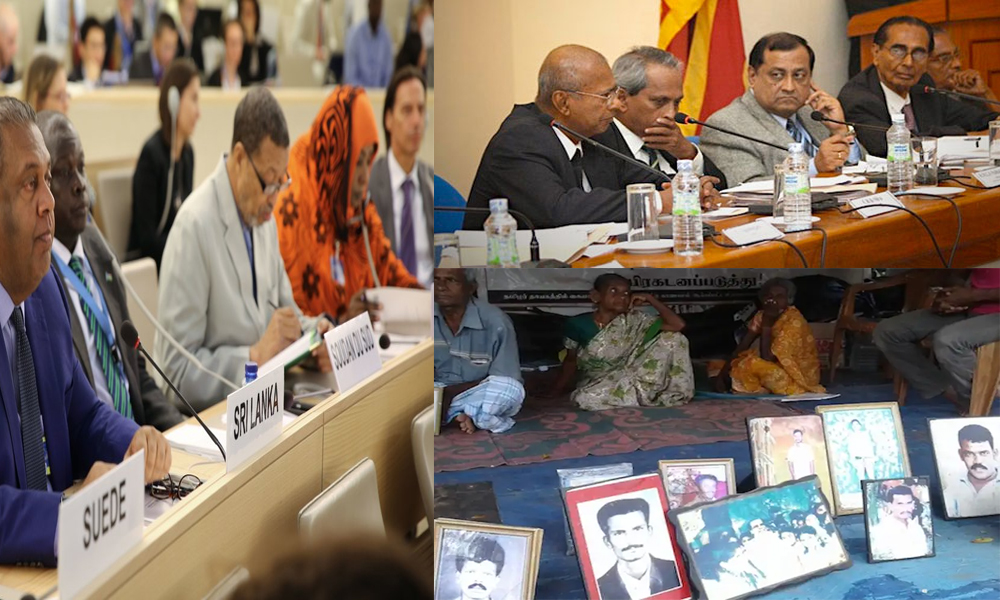

The timing of the decision leads one to suspect that, primarily, it has to do with the September session of the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC), where Sri Lanka is expected to face a tough and updated resolution on its rights record. The decision on TRC appears to be a part of a series of steps the government has been taking to weather the storm in Geneva. The promise of substituting the Prevention of Terrorism Act with a National Security Act, the delisting of six banned organizations and over 300 individuals allegedly connected with the LTTE, and the decision to open an office to liaise with the Tamil Diaspora are among them.

But barring the Diaspora liaison office and the lifting of the ban on entities, nothing in the above-mentioned list is new. They have been attempted earlier, but only half-heartedly and abandoned.

Will the TRC meet the same fate? Will the expectations generated among the victims of State terror and those of terrorists be fulfilled? The perpetrators of State terror can be traced and punished, but the perpetrators of terrorism cannot be tracked. The latter is among the killed or missing.

Also, would anyone in the Security Forces admit to war crimes and rights violations even when there is a provision for amnesty? And would the civilian victims of violations by the State’s personnel accept amnesty as a fair solution? Would nationalistic feelings allow the personnel of the forces to be exposed and punished? The road ahead for the proposed TRC is indeed hard.

The idea of setting up a TRC is seven years old. On September 14, 2015, the Lankan government announced a plan to establish a “Commission for Truth, Justice, Reconciliation and Non-Recurrence.” The then Foreign Minister, Mangala Samaraweera, had said that South Africa, which had set up a TRC, would advise Sri Lanka on this. But nothing happened till 2018 when the government again announced an intention to set up a TRC.

According to the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights, a conceptual framework was submitted on 16 October 2018 to the Cabinet, which decided to refer it to the Ministry of Defense. In March 2020, the UNHRC reported that the TRC proposal had not made any progress.

However, the 2018 concept paper is worth going into to get an idea of President Wickremesinghe’s thinking. It said that the TRC of Sri Lanka (TRCSL) will be established by an Act of Parliament. Its mandate would be to investigate and make recommendations in respect of complaints and reports relating to damage and/or harm caused to persons as a result of loss of life, or damage and/or harm to persons or property, (i) in the course of, or reasonably connected to, or consequent to the armed conflict, or its aftermath; or ii) in connection with political unrest or civil disturbances in Sri Lanka; or (iii) where such violations are in the nature of prolonged and grave damage and/or harm suffered by individuals, groups or communities of people of Sri Lanka.

Justifying the establishment of the TRC, the concept paper said: “Despite the appointment of numerous ad hoc commissions of inquiry during the past (like the Paranagama Commission, the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission, the Udalagama Commission, Mahanama Tillekeratne Commission) due to failure to implement recommendations made by those Commissions, it has not been possible to successfully prevent recurrence of conflict, or build confidence amongst all the people of Sri Lanka in the efficacy of measures to ensure non-recurrence, advance national unity and reconciliation, or identify and undertake administrative reform interventions that may be necessary.”

The proposed Act of Parliament would, inter alia, incorporate statutory provisions to appoint a Monitoring Committee which will “enable all Sri Lankan citizens, irrespective of race or religion, including families of police and security forces personnel, civilians in villages that came under attack by terrorists, security forces personnel and police personnel, and all affected persons in all parts of the country, to submit their grievances suffered during any phase of civil disturbances, political unrest or armed conflict that has occurred in the past, to the proposed TRCSL.”

“The proposed TRCSL should have sufficient administrative and investigative powers, including those granted to Commissions of Inquiry. This includes powers to compel the cooperation of persons, State institutions, and public officers in the course of its work. While the TRCSL will not engage in prosecutions, it should be vested with sufficient investigative powers. But the TRCSL’s recommendations shall not be deemed to be a determination of civil or criminal liability of any person.”

South African TRC

The experience of South Africa’s TRC (TRCSA) should indicate the kind of problems that TRCSL might face. TRCSA was established in 1995 after the collapse of the Apartheid regime. Its emphasis was on gathering evidence from both victims and perpetrators, but not on prosecuting individuals. While right-wing racists and the Security Forces demanded a blanket amnesty for themselves, the liberation forces and the African victims demanded Nürnberg-type trials (the trial of Nazis after World War II) which ended in punishments being given.

The South African TRC was established after the newly elected government solicited the opinion of a cross-section of the population and also the international community regarding accountability, reparations and amnesty. The consultative process lasted a year and culminated in the legislation, entitled: Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act 34 of 1995 (the Act), that established the TRC. The TRC went into abuses committed between 1960 and 1994.

To achieve these objectives, the Act established three committees: the Human Rights Violations Committee, the Reparations and Rehabilitation Committee, and the Amnesty Committee. According to the literature on the TRC, the commissioners were selected after throwing open nominations country-wide. Interviews were conducted publicly by an independent selection panel comprising representatives of all the political parties, civil society, and religious bodies in the country. Nelson Mandela, then president of South Africa, appointed Archbishop Desmond Tutu, as the chair of the TRCSA.

The TRCSA, holding public hearings, received more than 22,000 statements from victims. Victims of State as well liberation movement terrorism gave went to their feelings freely. 7,000 applied for amnesty and 1,500 got it. Such public exposure went a long way toward reducing the trauma of the victims. It was an educative and reformative exercise for the whole population eventually leading to a more reconciled and healthier South African society.

However, the top brass of the Security Forces did not cooperate. But the lower ranks did, with the violators applying for amnesty. Members of the liberation forces argued that they had done no wrong as they were fighting a just war. Eventually, even these were persuaded to testify.

Sadly, the post-Mandela governments were slow to implement the TRCSA’s recommendations, including its reparations program. It is reported that by the end of the first decade of the 21st century, few of the recommendations had been implemented. Nobody of consequence was punished. However, it was a cathartic and self-purifying process acted out publicly. It provided a dramatic start to a new South Africa.

If Sri Lanka establishes a TRC, it could also be useful, if only partially. But its prospects are dimmer compared to South Africa’s TRC, going by the fate of previous Sri Lankan commissions on human rights violations, and the generally hostile approach of the Sri Lankan polity to human rights violations.