N Sathiya Moorthy

12 March 2024

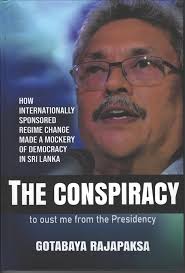

The most disconcerting aspect of former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s book, ‘The Conspiracy to Oust Me’, released recently, is not about what the book says or does not say. Instead, it is about the absence of a formal book-launch function, like the one, his chosen Defence Secretary, Gen. Kamal Gunaratne, had organised when he wrote his memoirs of the decisive ‘Eelam War IV’ before Gota had even thrown his hat into the ring.

Does the absence of a launch-function owes to anticipation of public protests at the venue, wherever? Or, was it also a reflection of his one-time comrades-at-arms and possibly senior family members too not wanting to be associated with the book and its contents at this ‘distance’ (!) in time? Or, was it because Gota just wanted to put out his side of the ‘story’ (?) and let it seep in, whenever, however.

There is more than one version of any story, and Gota has now put out his side. Going by social media posts and other group-chats, participants have pre-judged him with the prejudices that they still hold against him – and for the right reasons. Looking at the circumstances attending the ‘Aragalaya’ protests of 2022, critics on social media are right in blaming Gota for his share in causing the economic crisis? But was he the only one to blame?

Twin sins

Gota’s twin sins as President that contributed to the crisis two years back related to the huge tax-breaks he gave the big business to try and revive the economy post-Covid, and insulting the people’s plight by unilaterally ordering the import of ‘organic fertiliser’ from China as if it was the sole panacea for all the nation’s ills at the time. The problem was that neither of them had any effective consultation. If anything, all fair criticism and genuine suggestions were spurned.

It was becoming increasingly clear that Gota never had any clue of what they were all about. In comparison, his Prime Minister and two-term President, Mahinda Rajapaksa, his own elder brother, had a better understanding of what would work and what would not be acceptable to the people. It was becoming increasingly clear that long before Gota forced Mahinda to quit at the height of the Aragalaya protests, he had stopped consulting the other – or, even considering MR’s suggestions, with the seriousness it deserved.

Maybe, Mahinda would have saved his face and also a part of his 40-per cent strong voter-support if he had quit the government before being forced out. People who remember his loving hug of Gota after the latter survived an LTTE suicide-bomb attack a decade and more earlier, would know that he was incapable of doing it. To him, the family came first. To his detractors, it meant that the nation came last in the Rajapaksa calculations.

Otherwise, independent of favouritism charges in Sri Lanka, governments the world over have been attempting tax-breaks for industries to revive economies when they hit a downward spiral. Most western nations did it post-Covid and earlier after the ‘Global Melt-down’ of 2008. Some were successful, others failed. Sri Lanka was on the second list.

Stank sky-high

But the same cannot be said of the ‘organic fertiliser’ import, which stank sky-high from the very word ‘Go’. No, it was not about the organic fertiliser coming from China. It was and is more about the secrecy that surrounded the import and the inordinate pressure that was visibly brought upon the nation’s farm experts to clear the Chinese sample when they were all convinced that it would not suit Sri Lankan soil and weather conditions. Throughout the fertiliser import scam, one could not escape the feeling that the public discourse on the matter was kick-started in the country only after the fertiliser-load had left the Chinese shores. At least on that score, Gota has reportedly apologised for his wrong decision.

One can go on to charge the Rajapaksas, and not just Gota, with taking the nation the China way, which was among the causes for all the accumulated debts that could have been avoided in the first place. But then, the intervening Government of National Unity (GNU) of President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe did not fare any better.

To their collective leadership of the ‘Yahapalayana’ government should go the blame for converting the Chinese credit for the unviable Hambantota Port Project from the previous Mahinda era, into a 99-year lease on Sri Lankan territory, and thus compromising the nation’s sovereignty and security, as well.

Regime-change

Going by reports, Gota has blamed a ‘foreign conspiracy’ for his ouster. He does not seem to have produced any evidence. In comparison, elder brother Mahinda, after losing the 2015 presidential election, named names and said the US and other western embassies in Colombo had effected a ‘regime-change’. Given that the economic crisis and the Aragalaya protests that led to his exit were unprecedented, when Gota titled the book as ‘The Conspiracy…’, something much more was expected of the book, expected of the author.

Otherwise, Got has seemingly blamed himself for making two army buddies from ‘Eelam War IV’, one as the defence secretary (Gen Kamal Gunaratne) and the other as the Chief of the Army Staff (Gen Shavendra Silva). There were functional problems in their new roles, Gota had since divined. He did not seem to have asked the question if neither had problems working under a former lieutenant-colonel that Gota was and who as President was now the Supreme Commander of the armed forces.

Anyway, Gota’s exit did not lead to the exit of defence secretary Gunaratne. If anything, this was the only senior posting from the Gota regime that Wickremesinghe as successor President had retained. Elsewhere, a three-man panel of veteran commanders had found Shavendra Silva of insubordination and worse in controlling and/or putting down the Aragalaya protests, especially when and wherever it turned violent.

Legacy issue

Gota’s book has failed to convince anyone, least of all his critics from the past, especially from among the urban middle class. They have been commenting on the man in the social media from their past perceptions – not that they had known him enough personally, to comment on and criticise him eternally. It is still the expression of their residual anger against the Rajapaksas – or, of the political system which in their eyes, Gota had come to personify. It may not go away.

Yet, the critics of Gota in particular and the Rajapaksas otherwise, need to understand one fact before acknowledging the same. The entire economic crisis of 2022 was not their making. It was a legacy issue, and it had to come unstuck somewhere, sometime. The legacy commenced almost with Independence, the failure of the early UNP governments, the directionless nature of the successor SLFP government, which alone led to the instant birth of the militant JVP in 1965.

It was all followed by alternating confusion that was confounded by the two JVP insurgencies and then the ethnic violence and the LTTE war. No serious study has been undertaken by any of the worthy critics, either of individuals or of the system, to remove the chaff from the grain and tell the nation where the electoral politics ended and economic policy-making began.

While politically and otherwise it may suit everyone to pass on the blame to the Rajapaksas, especially Gota, at least economically-knowledgeable Sri Lankans have to acknowledge that it was basically a ‘systems failure’. Rather, the economic policies of successive governments, whether ‘market-oriented’ UNP or the ‘socially-driven’ SLFP, later SLPP, were to blame, and needed to be reformed.

For the present, Wickremesinghe as President has taken to the extreme of the IMF conditionalities, which could not be avoided if the economy has to fall into an even gear. But all the critics of Wickremesinghe, who are mostly politicians or trade unionists, have been criticising his decisions, especially on price and tariff hikes, piecemeal.

Neither they, nor the so-called economists among the urban middle class critics of this government or of the Rajapaksas have given an alternate route, if not an outright new model. That will remain the nation’s bane as poll-time populism takes over and economic planning, if at all there is one, goes for a toss.

Arson attacks

There is another aspect of the Aragalaya protests for which the critics of Gota and the Rajapaksas cannot blame them? Not one of them seems to have raised their voice against the orchestrated violence that targeted the properties of ruling party leaders, starting with then President Gota to present President Wickremesinghe, then Prime Minister, and dozens of MPs and others. It was a pre-meditated arson-attack, which neither the police, nor the armed forces tried to put out.

Incidentally, the arsonists, in a separate show of strength, burnt down Wickremesinghe’s private home – and also tried to take over, if not set fire to the Parliament Building, too. That they blocked the President’s Secretariat is one thing, occupying the official residence of the nation’s Head of State was another, and putting out the ‘GoGotaGama’ setting on capital Colombo’s Galle Face Green was a third one.

Among them all, the last one alone was an acceptable form of democratic protest, so to say. The nation’s population that was driven to hunger and an eternal shock from which they would never be able to recover in full were justified in doing so. But the way the so-called protestors celebrated their takeover of the presidential residence does not fit into any form of democratic demonstration unless the ‘Arab Spring’ and the ‘Orange Revolution’ were the reference-points.

Inherent vulnerabilities

That flags the question: Should Gota have left sleeping dogs lying? Or, should the critics of Rajapaksas too to leave their own sleeping dogs, too, to lie? There was something more to it all — and those truths need to be brought out. Even more so, the realities of the nation’s economic capabilities and inherent vulnerabilities, to which the societal aspirations might have also been a contributing factor.

It means the nation as a whole, including the critics of the Rajapaksas and/or of the political system as a whole, should put the past behind – and start looking for clues to economic recovery and political accountability. After all, the Supreme Court that found the Rajapaksas as the cause for the ‘economic crisis’ did not say enough about the why and how of it.

It was the right decision at the right time, but for the wrong reasons. That does not solve anybody’s issue, least of all that of the nation and its vast population.