By P.K.Balachandran

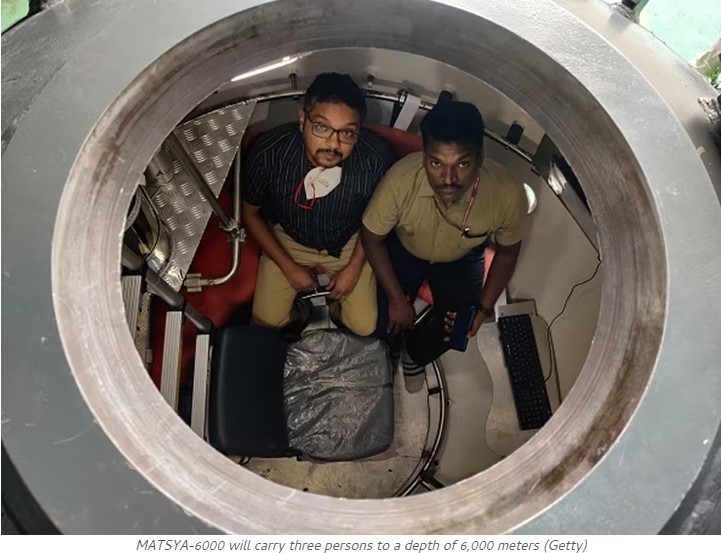

India’s National Institute of Ocean Technology (NIOT) in Chennai is planning to send in 2025, a manned submersible named “Matsya 6000” to a depth of 6,000 meters to explore mineral resources.

In the first phase, in February-March 2024, the submersible carrying three scientists will be sent 500 meters below. Deep sea trials at 6,000 metres will start in the last quarter of 2025. These experiments are part of the Samudrayaan (Ocean Craft) mission, launched in October 2021.

If the mission succeeds, India will be joining the elite club of nations comprising the US, Russia, Japan, France, and China that have niche technology and vehicles to carry out undersea activities.

The economic stakes are stupendous. The mineral resources in the Indian Ocean region allocated to India by an international agreement are estimated to be 380 million metric tonnes.

Dr G.A. Ramadass, Director of NIOT told ABP Live that the indigenously-developed Matsya 6000, will explore deep ocean mineral resources such as nickel, manganese, cobalt, and rare earths.

The Samudrayaan mission will propel India to an elite club of nations comprising the US, Russia, Japan, France, and China that are developing manned underwater vehicles to carry out deep-sea activities.

The Indian government has allocated a budget of Rs. 4,077 crore (US$ 492 million) for five years for the Samudrayaan project.

In a paper published in June 2023 by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Dharshana Baruah, Nitya. Labh and Jessica Greeley say that the entire Indian Ocean mineral resources field covers 300,000 sq.km with 1.4 billion tons of nodules valued at over US$ 8 trillion. India is entitled to get a share of that cake. The Indian Ocean area allocated to India for exploitation has 380 million metric tonnes of minerals.

In 2022, the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and the UN International Seabed Authority (ISBA) signed an MOU to collaborate on sustainable seabed mining in the region. In 2021, the Indian government approved the Deep Ocean Mission to develop deep-sea technologies for the exploration and sustainable use of ocean resources.

China, Germany, and South Korea have also received contracts to pursue seabed mining in the Indian Ocean

Blue Economy

Oceans make up 70% of the world’s surface. But the Deep Ocean is 95% undiscovered till date.

India is bordered by deep seas on three sides, has a 7,517 kilometres-long coastline and 1,382 islands. Its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) stretches over 1.6 million sq.km. About 30% of India’s population is living in coastal areas. Therefore, the ocean is a major economic factor supporting fisheries and aquaculture, tourism, livelihoods and blue trade in India.

In 2013, the Geological Survey of India acquired the deep-sea exploration ship ‘Samudra Ratnakar’ from South Korea. A state-of-the-art platform, the Samudra Ratnakar is equipped with sophisticated deep-sea survey instruments like Doppler profilers to measure water currents with sound using a principle of sound waves called the Doppler effect. The vessel has multi-beam sonars, acoustic positioning systems, marine magnetometers and a marine data management system, which give it a qualitative edge over other survey ships, says Cdr.Abhijit Singh of the Institute of Defence Studies and Analysis (IDSA).

India already had some deep-sea exploration capability in the form of the Sagar Nidhi a research vessel operated by the National Institute of Ocean Technology.

Geopolitical Dimension

The increasing presence of rival China in the Indian Ocean is a major reason for India’s interest in deep-sea exploration. China’s survey ships and underwater drones have been operating in the Persian Gulf, the Southwest Indian Ocean, the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea, worrying India’s strategic planners, points out Prakash Panneerselvam in The Diplomat. China had established a lead over its competitors in 2013 itself, said Cdr. Abhijit Singh of the IDSA.

“In 2011, when the International Sea Bed Authority (ISBA) decided to allow the China Ocean Mineral Resources Research and Development Association (COMRA) to undertake exploration for poly-metallic sulphides in a 10,000 sq. km area in the south-west Indian Ocean, it caused a flutter in the Indian strategic community, which saw the development as a geo-strategic gambit aimed at extending China’s footprint in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR),” Cdr. Singh recalled.

“A 15-year contract with the seabed authority in 2001 had given China rights to explore 75,000 sq. km of seabed for poly-metallic nodules (small rocks containing metal ore – manganese, copper, cobalt, etc) in which it has shown rapid progress in extracting the minerals. The license to explore the Western Indian Ocean seabed was, in major part, attributable to a concerted effort at scouting the seas and gathering evidence for the presence of mineral nodes on the sea bed.”

“In fact, China’s mining rights in the IOR were given six years after a Chinese government-sponsored expedition team found clues of an enormous belt of poly-metallic sulphides in a deep-sea rift south of Madagascar,” Singh pointed out.

India followed China into this field. ‘Deep-sea mining’ was officially recognised in India as a frontier of scientific research by a Vision Plan outlined by a National Security Council policy paper in 2012.

The government formulated a national Polymetallic Nodules (PMN) program that led to India’s getting a pioneer investor status with exploration rights over an area of 150,000 square kilometres in the Central Indian Ocean Basin (CIOB) under the UN Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Cooperation with Japan began in November 2012 for the exploration and production of rare earths. Following this, a monazite processing plant was set up in Odisha.

However, India has a long way to go. It started late. Although it was allotted 150,000 sq. km in the Central Indian Ocean Basin by the International Sea bed Authority (ISBA) in 2002, it was lax in exploiting it. Further, mining rights in many of the blocks in the south-west Indian Ocean had to be surrendered to the ISBA, Abhijit Singh pointed out.

But subsequently, through periodic relinquishments, an area of 75,000 kilometres square was retained by India, points out Mayank Agarwala in a 2021 piece on the environment website www.news.mongabay.com.

But under-sea exploration and exploitation won’t be easy because it needs modern equipment and trained manpower. The commercial viability also has to be considered. And safety has to be ensured.

Safety Concerns

Amid concerns over deep-sea explorations following the disaster that visited the submersible Titan in which five high-profile persons died on their way to explore the wreck of the Titanic, NIOT revisited the specifications of the Matsya 6000 module.

Dr Ramadass asserted that the Matsya 6000 is certified by the Norwegian certification agency, DNV (Det Norske Veritas), which has experience of certifying submersibles up to 10,000-metre water depth. Further, the hull or the sphere is made of titanium alloy. Structurally, it is the best design possible and the best material possible, he emphasized.

It is noteworthy that the submersible Titan was never certified or classed by marine organisations.

Environmental Impact

There is another aspect to be considered – damage to the marine environment caused by sea bed mining. In a March 2023 story, the website www.panda.org pointed out that many countries had begun asking for a “precautionary pause, moratorium or ban” on deep-sea mining.

Those countries which expressed such concern were Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Finland, France, Germany, New Zealand, Palau, Panama, Samoa, Spain and Vanuatu.

Their fear was that the damage caused by large-scale mining could do irreversible damage to the sea bed, its features and resources.