by Vishvanath

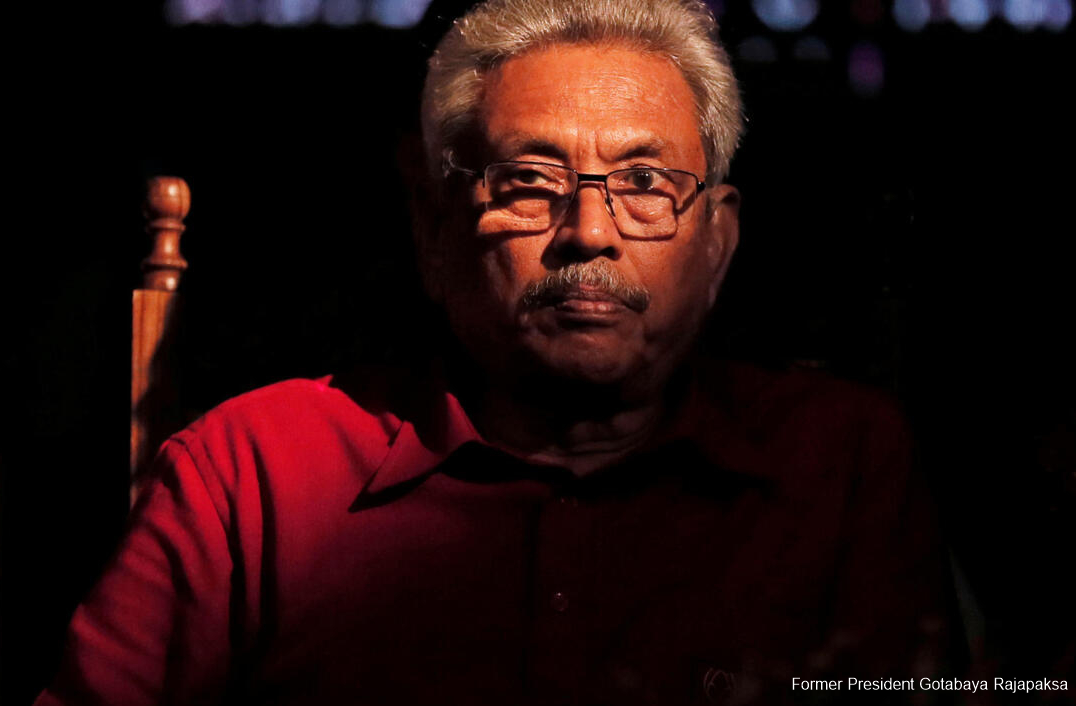

Ousted President Gotabaya Rajapaksa maintains a very low profile, but he happened to be in the news last week. Media reports that he had been given a state-owned house at Stanmore Crescent created quite a stir with some Opposition MPs demanding to know why the government had allowed him to shift from his official residence at Malalasekera Mawatha to the house reserved for the Foreign Minister at Stanmore Crescent.

Some media reports even claimed Gotabaya had asked for a house in a calm and quiet neighborhood. Incumbent Foreign Minister Ali Sabry lives in a privately-owned house and his official residence remains vacant. Speaking in the parliament, Minister Sabry refuted claims that he had been responsible for the allocation of the Foreign Minister’s official residence to the former President.

Hostile reaction

Going by the public reaction to the above-mentioned reports, as evident from a host of social media posts on them, people’s resentment at Gotabaya and the other members of the Rajapaksa family has not subsided, yet. They are protesting though the Constitution specifies the entitlements for former Presidents such as pensions, official residences, offices, staff, transport, and security besides privileges such as the order of precedence; the widows and widowers of former Presidents are also entitled to official residences, security, pensions, etc.

People have never been well-disposed towards the presidential entitlements and pensions for the MPs. Theyhowever used to take them as a fact of life, and it was only after the collapse of the economy under Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s presidency that they began to protest against the retirement benefits of Presidents and their spouses.

The JVP has sought to capitalize on public ire at four former Presidents and a widow of a slain President enjoying presidential entitlements. It has said it will take steps to do away with them if it forms a government. This offer may have resonated with the irate public, who are undergoing untold hardships. The JVP must be actually keen to carry out what it has offered to do because it is well-nigh impossible for it to poll enough votes to secure the executive presidency; whether it will be able to capture power in the parliament is also in serious doubt. The major parties that have produced Presidents have refrained from making such a promise.

Hero to zero

Of all retired Sri Lankan Presidents, only Gotabaya has had to live in seclusion of sorts for obvious reasons. Three of his predecessors, namely Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, Mahinda Rajapaksa and Maithripala Sirisena, are still active in politics, and have a considerable following. Is Gotabaya alone to be blamed for his fate?

Gotabaya must be ruing the day he decided to run for President. When his elder brother, Mahinda Rajapaksa lost the 2015 presidential election, and the UNP-led Yahapalanagovernment launched a hostile campaign against the Rajapaksa family thereafter, their loyalists gravitated around Gotabaya and stimulated his presidential ambitions for their own sake rather than his or his family’s. Some of them banded together as Viyathmaga, which mobilized professionals, intellectual and business leaders in support of Gotabaya’s presidential bid.

Gotabaya was a very successful bureaucrat, and earned a name for himself as the wartime Defense Secretary during the Mahinda Rajapaksa presidency. He also proved himself as the Secretary of the Urban Development Ministry. He was instrumental in putting an end to the haphazard disposal of garbage, and ridding urban areas of heaps of municipal waste—a problem that successive governments had failed to tackle for decades. He was also responsible for many urban beautification projects, such as the establishment of recreational parks, which helped him win the hearts and minds of the socially-conscious and politically-active middle class people. He became known as a doer, and not a moaner.

President Maithripala Sirisena was troubled by the so-called wimp factor, and the people were looking for a tough leader to take the country in a new direction. A former military officer and successful bureaucrat, Gotabaya became their choice, and he instilled high hopes in them. The country had come under a pall of uncertainty after the Easter Sunday attacks, and the people needed a strong President to safeguard national security and get tough with those who stood in the way of achieving national progress.

Soon after the election of Gotabaya as the President, the youth went on a wall painting spree, which was indicative of their hope of a better future. But less than two years later, they took to the streets, and set up the ‘Gota Go Gama’ protest site, calling for the ouster of Gotabaya; they continue to use their creative talents to carry out scathing attacks on him, and are now questioning why he should be looked after by the state.

My way or the highway

Once a soldier, always a soldier, so to speak. Members of the armed forces generally cannot get rid of their military mindset even after returning to civvy street. So, Gotabaya continued to look at things in binary in typical military style, even after becoming the President, and expected his orders to be followed, no matter what. He was known for his ‘my-way–or-the-high-way’ policy. Hence his declarations at a public function during the early stages of his presidency that his word had to take precedence over government circulars and state officials had to do as he said.

Overconfident, Gotabaya apparently took statecraft and politics for granted. He expected all his orders to yield the desired results and did not care much about their consequences.End, he apparently thought, justified the means. He believed in railroading everyone into doing as he said. His approach to politics and governance lacked flexibility and pragmatism. Even in the face of proof that he was wrong, he remained obdurateand dug his political grave in the process. An experienced politician holding the presidency would have handled such situations differently and tactfully.

Wrong advisors

It is popularly believed that President Gotabaya Rajapaksa failed because he and the members of his kitchen Cabinet lacked political experience. There is some truth in this assertion, but he had among his advisors some very experienced bureaucrats, who unfortunately sought to promote self-interest, built walls around him, preventing those who held dissenting views from gaining access to him. He also heeded the wrong advice, as evident from his disastrous organic fertilizer experiment, which had a devastating impact on the agricultural sector and created conditions for protests that would later snowball into a countrywide uprising. Most of his advisors who persuaded him to ban agrochemicals almost overnight were not even agricultural experts. Today, they have disowned him and are trying to absolve themselves of the blame for the fertilizerdisaster and the resultant political upheavals and economic losses.

What became the undoing of the Gotabaya presidency was the SLPP government’s pathetic failure on the economic front. It was a colossal blunder for the SLPP to slash taxes and even abolish some of them to win the 2020 general election. A steep drop in the state revenue due to tax cuts compelled the government to step up money printing and the Covid-19 pandemic aggravated the situation with cash handouts being distributed liberally for political reasons, and lockdowns taking their toll on the economy. The resultant rupee crisis, excessivemoney printing, soaring inflation and the rapid depreciation of the rupee led to the depletion of the country’s foreign currency reserves and the so-called dollar crisis.

Gotabaya was misled by his economic advisors, who prevented him from seeking IMF assistance before it was too late. They apparently expected China to step in to shore up the dwindling foreign currency reserves and thereby help stabilize the economy. But nothing of the sort happened. The country had to opt for a disastrous debt default and was left without foreign currency even for essential imports and shortages, which led toqueues for essential commodities, especially fuel. Public anger welled up and found expression in the Galle Face protest campaign or Aragalaya.

Political tug of war

Another reason why Gotabaya failed as the President and has become unpopular to the extent of people protesting against his entitlements as a former President was a tug of war between him and his political party. The SLPP parliamentary group, which Basil Rajapaksa has kept under his thumb, did not fully cooperate with Gotabaya, who would have been able to controlit if he had been its leader.

Making matters worse, Mahinda stopped getting involved in party affairs and let his young brothers run the government. That approach proved to be a costly mistake. The SLPP suffered a split with some of its dissenting MPs breaking ranks, and the government lost direction. The premature end of the Gotabaya presidency came as no surprise.

Another worrisome proposition

Will the SLPP and President Ranil Wickremesinghe, who is dependent on it for parliamentary support, find themselves at loggerheads, rendering the government dysfunctional? This is the question being asked in political circles.

General Secretary of the SLPP Sagara Kariyawasam continues to strike discordant notes, though some SLPP stalwarts are praising President Wickremesinghe, who can now leverage his power to dissolve the parliament to bend the SLPP MPs to his will.

Whether the President and the SLPP will iron out their political differences and work together to keep their hold on power, thereby maintaining the semblance of economic stability that has come about and fortify their shared future remains to be seen.