In September 1961, the UN was in danger. Secretary-general Dag Hammarskjold had died in a tragic plane crash, and Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet leader, was insisting the organization acquire a new form of leadership that would doom it to lasting deadlock and irrelevance.

US president John F Kennedy rose in the General Assembly chamber and told delegates: “The problem is the life of this organisation. It will either grow to meet the challenges of our age, or it will be gone with the wind?.?.?.?Were we to let it die,?.?.?.?we would condemn our future.”

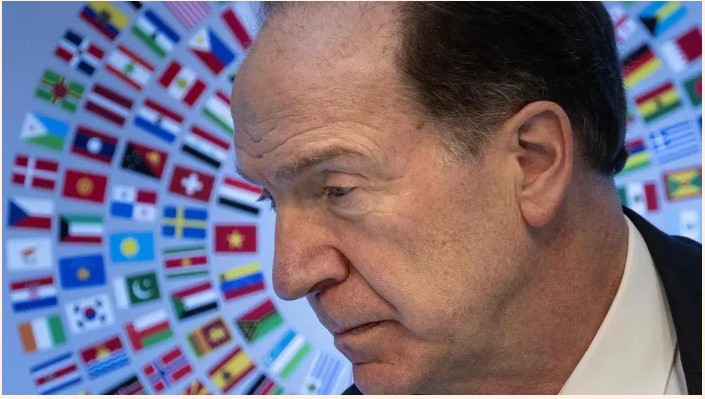

Today, the World Bank is coasting towards a similar fate, absent from the stage while multiple threats accumulate — from climate change, through the war in Ukraine, to crippling sovereign debt crises in low-income countries. And now the Bank’s president, David Malpass, a Donald Trump appointee, has abruptly announced his intention to resign.

Whoever succeeds Malpass will do much to decide whether this fabled institution ultimately perishes or survives. Here are five priorities for them to insist on.

First, climate change. We need to spend trillions of dollars to combat global warming, yet the World Bank Group’s entire disbursements were no more than $67bn for the fiscal year 2022, of which only a fraction was net disbursements.

The Bank must double down on climate investment by creating a new climate-focused bank-within-a-bank which would bring to bear the organisation’s full financial clout and resources. Combating climate change also requires a bank culture focused on rapid execution and implementation, using private-sector expertise to leverage multilateral funding with private capital and institutional assets.

Second, the World Bank’s finances need immediate reform to meet the future needs of low and middle income countries. While the scale and financial model of the Bank was appropriate at its inception, today the size of its lending and its inability to use modern financial tools and easily unlock private capital makes it less relevant. It is not a good sign that Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, has approached BlackRock to finance his nation’s reconstruction. It was the World Bank that underwrote the reconstruction of Europe and Japan after the second world war.

Third, the new president must enhance and unleash the Bank’s unmatched resources of intelligence, research and planning against climate change. Much like the successful Consultative Group on International Agriculture Research to combat global hunger, the Bank must emphasise how quickly the climate clock is ticking, place itself at the centre of the struggle and acquire, and mobilise, world-class expertise in climate, open AI and technology.

Fourth, since the second world war, some of the most brilliant solutions to the world’s problems have come from young entrepreneurs and innovators in the global south. In 1961, a World Bank loan to Japan made possible the bullet train network that became an example to the rest of the globe. It is time for the Bank to be at the cutting edge of such local private-sector innovations once more.

Finally, the World Bank must recognise that fighting injustice and inequality is just as important a part of its historic mission as tackling hunger and disease. The institution was founded in 1944 on the premise that the best route to a peaceful and prosperous postwar world was a system of democracies based on Franklin Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” — freedom of speech and religion, freedom from want and fear.

Kennedy’s words to the UN in 1961 resonate again in our age of an endangered climate and declining democracies: “Never have the nations of the world had so much to lose, or so much to gain.”

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...