The Colombo city may be ageing, but the area it encompasses, save its poor quarters studded with slums and shanties, looks beautiful thanks to some gentrification projects carried out by successive governments. It is home to about 750,000 people and its transient population stands at about one million. In one waits in a chill-out joint or even in a busy street and watches the world go by, the city looks normal. The same goes for other towns and their sprawling conurbations. Looks, however, can be deceptive.

That the Colombo city has been divided into 15 postal zones is only too well known. There are also 23 police stations within its limits to ensure public safety. But little known is the fact that dangerous criminal gangs have also divided Colombo into zones so that they do not have to tread on one another’s corns and get involved in bloody turf wars, which, however, are not uncommon. This is the seamy side of Colombo.

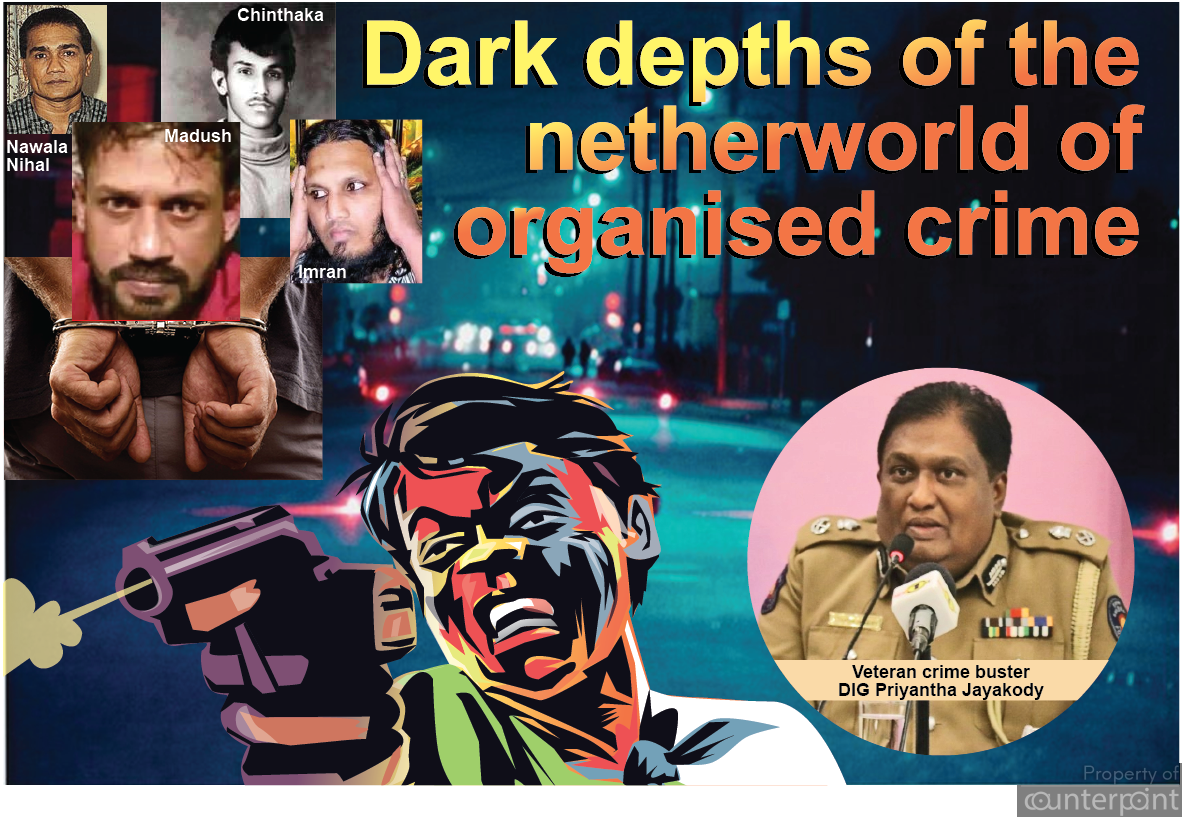

There are over a dozen major criminal gangs operating, in Sri Lanka, at present, and most of them are based in Colombo and its suburbs. Counterpoint, in its latest investigation, attempts to shed some light on the local underworld and its activities that are going on below the radar. The following interview with a veteran crime buster, Deputy Inspector General of Police (DIG) Priyantha Jayakody, who has brought several underworld gangs to justice, is an introduction to a series of articles to follow. It deals with the genesis of organised crime, the evolution of the underworld and the current situation in the country.

CP: There seems to be a lull in the underworld activities these days. What do you think has led to this situation?

PJ: Yes, there has been a drop in underworld activities. I think the arrest of two notorious criminals, Makandure Madush and Kanjipana Imran is the reason. Madush is the leader of the most powerful underworld gang in the country. Their arrests have led to a 90% decrease in organised crime and dealt a severe blow to the heroin trade.

CP: Is there a particular period in history, to which you can trace the genesis of the netherworld of organised crime in this country?

PJ: I think the beginning of organised crime in this country is lost in the mists of time, though the emergence of the underworld in the present form is or more recent origin. Activities of criminal gangs have been reported for many decades though the threats they posed to society were not as formidable as they are today. There are records that criminal gangs operated even under the British rule. Saradiel led one of them. He robbed the rich and committed other forms of crime.

In the 1940s, the emergence of two new industries in the country—transport and liquor—led to the growth of organised gangs, who were tasked with looking after the interests of the moneybags involved in those thriving businesses. These two industries were dependent on hired guns to maintain and expand their operations amidst stiff competition from others and the attendant rivalries; the bus owners and liquor dealers armed and financed criminals, who used to have violent clashes. They were led by notorious characters such as Kegalle Chutte, Kalu Gamini and Madavi Piyadasa.

Similarly, there were other criminals like Maru Sira, Polonnauwe Podi Wije, Beliatte Ukkuwa and Wanasara in the provinces. All of them perished in confrontations with the police. There were some gangs that emerged in urban centres; they were led by some criminals like Cutex Priya, Angoda Chana, Ampare Suda, Cheena and Maradane Choppe.

In those days, the 400,000-rupee heist, at a commercial establishment, in Kollupitiya, sent shock waves across the country. It was masterminded by an underworld figure known as Nawala Nihal. Some other criminals such as Noel Amarasinghe were also involved in it. Even a film was made on the incident. Such high-profile crimes were rare in those days and received wide publicity.

CP: Most of the underworld figures in days of yore were well adept at hand-to-hand combat. They, in fact, became heroes of sorts, because of their martial arts skills. But, today, any weakling with a homicidal streak can become an underworld character thanks to the proliferation of lethal weapons. When do you think this situation came into being?

PJ: Yes, today, criminals use weapons to kill unarmed people. Anyone can become an underworld figure by killing innocent people and unleashing barbaric violence. All it takes is a savage mindset plus a weapon. But he has to bear in mind that crime does not pay.

The reign of terror (1987-89) marked a crucial phase in the evolution of the underworld in its present form in this country. That era saw the birth of many vigilante groups which carried out extrajudicial killings. Politicians who could not get their dirty work done by the police and the armed forces used those gangs.

Those armed groups were paid salaries and given arms and protection to carry out killings. Criminals such as Arambawelaga Don Upali Ranjith or Soththi Upali, U Liyanage and Dhammika led the government sponsored criminal gangs. They became a law unto themselves.

In the CP edition of 5 April, 2019, we discussed the issue of weapons the then UNP government made available to various groups in the late 1980s. We said:

“That the Sri Lankans government helped and created armed groups or vigilantes to combat the LTTE and the JVP is only too well known. Besides, weapons and grenades were issued to political parties to defend themselves against the JVP hit squads, in the late 1980s.

Chris Smith (in his report on Small Arms Survey in 2003) has estimated the number of weapons, so distributed, to be 11,000. Police officers, interviewed by Counterpoint, said they believed the number could be much higher and there were no proper records of the weapons so issued. Many of those arms were not returned.

The National Commission against the Proliferation of Illicit Small Arms (NCAPISA) quotes a senior police officer, attached to the Police Central Armoury, Colombo, as having said in 2006 that about 80% of those weapons were returned. Even if this claim is true, the fact remains that more than 2,200 lethal weapons have not been returned if one goes by Smith’s figure of 11,000.

Among the arms issued to those threatened by the JVP were automatic and semi-automatic rifles. Years after the defeat of the JVP, a cache of weapons was found behind a false wall in a political party office in Punchi Borella, Colombo.’

Those criminal gangs were responsible for numerous abductions and murders. While doing dirty work for politicians, they also committed crimes to further their own interests. This, I believe, led to the emergence of the underworld groups in its present form. The police could not act against them due to political interference.

CP: Some gangs emerged from among the members of different ethnic communities or in other words, the underworld was divided along the ethnic lines just like the polity. What are your views?

PJ: Yes, some gangs maintained ethnic identities. There were Sinhala, Muslim and Tamil groups. One Tamil gang operated from Maligawatte and took members of the Sinhala and Muslim gangs. Led by Sudakaran, it consisted of criminals such as Sinnajapan, Christopher, Ramesh, Nauffer (a Muslim), Nadaraja and Wijepalan.

A Muslim gang led by Barber Imtias, a local government politician, emerged in the 1990s, in Maligawatte. That was the beginning of the so-called Muslim underworld. Its members were Ayubkhan, Faji Biah, Akram, Mawasmi, Anama, Diga Faizer and Leemolawatte Rizwan.

Several Sinhala gangs came into being to counter the Tamil and Muslim groups. They were led by Kaduwela Wasantha, Kudu Lal, Prince Kolum, Mikat and other criminals operating in the suburbs of Colombo.

By 1988, the narcotic trade had got established in the country and all underworld gangs took to the drug business to earn huge profits. It was much more profitable than contract killings.

The police found, in 1998, that there were 18 powerful underworld gangs in the country. The names of their leaders and their strongholds are as follows:

All these gangs worked for politicians, who got them to carry out illegal operations, which were legion. They terrorised the people, especially the business community, which had to a lot pay protection money. All the aforesaid criminal kingpins are thankfully not among the living, today.

At present, the main sources of income for these gangs are heroin trade and extortion. They become very active during elections, when their patrons need their services. All governments have enlisted the support of the underworld for the last three or four decades. The worst period was under the Premadasa government. (Next issue: Underworld zones in Colombo)