“I will **** you up.”

“We will teach you a lesson, low-caste b***h”.

Hate, it’s online now. Hate, it’s in the memes on your phone. Hate, it’s in your Twitter notifications.

Put yourself out there on social media, and someday, somehow, you’ll encounter a wall of hate. If you’re a woman, a person of colour or an LBT person, you are likely to see some choice language or graphics channelled your way. Women, in South Asian countries in particular, experience significant cyber violence. Such harassment can encompass different degrees of violence and aggressiveness, but is always violent. Directly connected to sexism and misogyny, it often manifests also in connection with other discriminatory practices. It can have dramatic consequences on the lives and rights of the women affected. In a study on cyberviolence in Bangladesh, Farah Akhter noted that every year there are 11 suicide attempts by women due to cyberviolence. In India, commentators have noted that when a victim belongs to a marginalized society, they are targeted even more, and that the help they receive is often insufficient. In Sri Lanka, anecdotal evidence, as well as data collected by researchers show that, in recent years, there has been a rise in sexual harassment and commentary online. These cases are so serious that they escalate to and often include violence. Much of this violence targets women and LBT communities. One such report is a study funded by Counterpart International and titled “Opinions B*tch: Technology Based Violence Against Women in Sri Lanka”. The study was jointly conducted by researchers from Ghosha, The Center for Policy Alternatives, and Hashtag Generation.

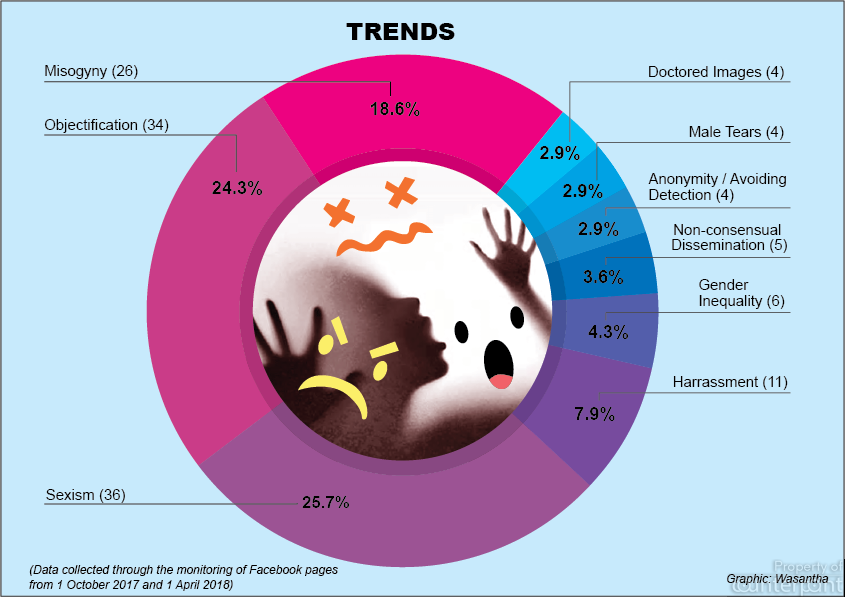

This research monitored 52 Facebook pages containing English Sinhala and Tamil content over a period of six months. Meme pages were monitored, as well as public Facebook groups, and the pages of public figures. This was supplemented by focus group discussions with members of the Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender (LBT) community on their experiences relating to technology-based violence, as well as through interviews with female politicians and activists outside Colombo. Researchers also used a snowball sample, following leads that led from one page to the next. Discrete case studies were also collated, in order to reach incidents outside of the reach of the purposive sample.

“What emerged”, notes the study “was a clear pattern of speech that was sexist, or objectified, harassed or otherwise targeted women and members of the LBT community” ((Wickrematunge et al 2019: i). One of the issues that arose from this research was the culture of sexism and misogyny that exists on Facebook. This was common across all three languages and was an extension of the casual sexism that already exists on Facebook and, arguably in Sri Lankan culture in general. The research notes that this is often packaged as ‘humour’. There were also instances where the page or poster seemingly defends women whilst in fact propagating violence against them. In this way, the research notes that the online space is really only “replicating and sometimes augmenting structural inequalities against women.” ((Wickrematunge et al 2019: 19)

There is also a strong culture of anonymity on many of these Facebook pages, and so it is difficult to ascertain who curates such a page. Neither are followers or commentators easily identifiable as they use fake identities or markers to disguise their true selves. This makes it difficult to report perpetrators. The study also discovered that these pages and commentators found ways to manipulate and thus work around Facebook Community guidelines, employing tactics such as posting only links, or placing text over images, or only liking posts without sharing them.

“Some page administrators can be seen explicitly telling commenters that they can’t post the photos directly as then, the page would be reported. They directed them instead to an external link off Facebook, or say that they would send the photos to their Inbox directly.” – (Wickrematunge et al 2019: 23)

The study also notes the other serious flaw in Facebook’s ability to administrate these issues: language. When harmful content is in a non-English language, Facebook cannot always ascertain if the text is violent or not. Users exploit this by flaw posting an innocuous image with violent text.

Other worrying issues highlighted in this study, are those that extend into other parts of social media. For example, an in-depth investigation of a certain Facebook page also led to the discovery of a WhatsApp group in which the all-male group sent each other offensive messages. Such groups share porn and sometimes leaked photos and videos, including those of underage girls, or intimate pictures and videos of celebrities. Other pages and groups were used to share women’s private information.

The Focus Group Discussions also uncovered many stories of harassment, abuse, threats and extortion experienced as women and LGBTIQ people expressing themselves on the Internet or with the use of technology. “Women, girls and LGBTIQ people are constantly silenced online for behaviour that doesn’t fit heteropatriarchal norms” (Wickrematunge et al, 2019:27)

LBT persons are especially vulnerable to cyberviolence. LBT persons who express their sexuality online are often at the receiving end of violence and ridicule. Such persons are often insulted using gendered terms or accused of being promiscuous or worse. Many LBT groups and individuals then use pseudonyms, or are online only in closed groups in order to minimise the kinds of violence they face. Having to operate with such discretion, however, handicaps the ways in which LBT groups can build solidarity and support online.

Other groups that are often the target of such online violence are women political candidates, activists, academics, journalists and similar public figures. There seems to be a strong connection between women who dare to speak and the violence that is sent their way.

The report ends with a series of recommendations that policymakers in Sri Lanka would be wise to take up. They include, but are not exclusive to: the introduction of national inclusive ICT policies, strengthening law enforcement and the judiciary to adequately address these issues, capacity strengthening and awareness raising for women and girls, teaching online literacy and comprehensive sexual education across curricula, implementing existing human rights laws and addressing technology related violence without harming freedom of expression.

Most important of all these recommendations, is the need to treat technology related violence as violence.

The full report can be accessed here: https://drive.google.com/file/u/2/d/16ohQ7P2K08qz-kgiQUfSr0JCGvxDLHNR/view?usp=sharing