Although not a single Briton or any government property was attacked, the British rulers of Ceylon mistook the Muslim-Buddhist riots of 1915 for a serious bid to overthrow them.

However, the thoughtless imposition of a particularly draconian version of Martial Law for full three months ended up creating grounds for the Ceylonese independence movement.

In his book “Riots and Martial Law in Ceylon -1915” the Tamil politician and lawyer Ponnambalam Ramanathan says that the Hambayas of Kandy (who were Muslim traders of South Indian origin) had objected to Sinhalese Buddhists playing music in front of their mosques. The Basnayake Nilame of the Gampola temple took the case of the Buddhists to the Kandy District Court. They argued that as per Art 5 of the 1815 Kandyan Convention, the British rulers were duty-bound to ensure that all Buddhist customs including playing music in religious processions were observed.

In his ruling of June 4, 1914, Judge Paul. Pieris said that music is an essential part of Perahera rites and that the Kandyan Convention was binding and unalterable.

However, the Hambayas took the case to the Supreme Court. On February 2, 1915, the Supreme Court reversed the order of the District Court, saying that the application of the Kandyan Convention would be subject to the Police Ordinance of 1865 and the Local Bodies Ordinance of 1898 which required licensing of processions. In other words, the right to take processions was not unfettered and automatic.

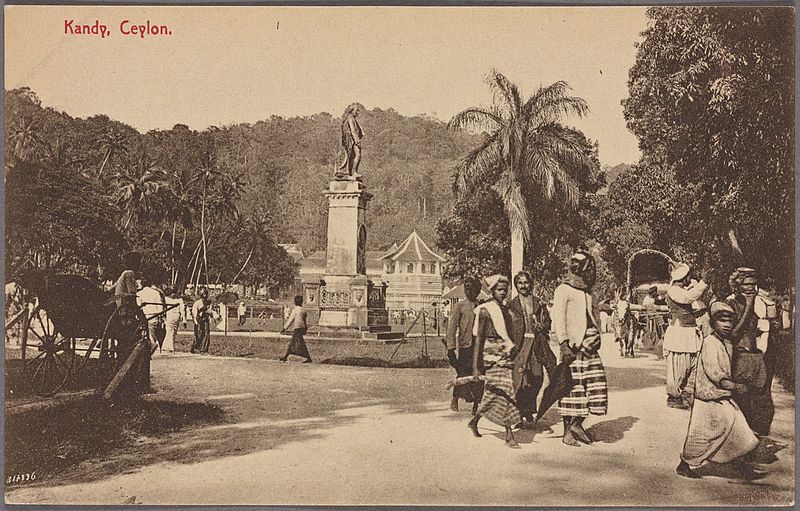

The Kandyan Buddhists were jolted by the ruling. Nevertheless, they applied for a license to hold a procession on the birthday of the Buddha that fell on May 28, 1915. The Hambayas opposed it. The Kandy District Government Agent told the Buddhists that the procession could pass through the Castle Hill Street mosque (in Kandy) after it was closed at 12 midnight. But this stipulation was made without first taking the consent of the Hambayas. When the procession reached the mosque at 1 am on May 29, it was fully lit and open and stones were hurled on the procession. What followed was unbridled looting and destruction of Hambaya shops and properties. A Sinhalese youth fell to a bullet fired by a Hambaya, but the assailant was not arrested which further enraged the crowd.

Ramanathan says that while the town folk took the incident in their stride, villagers around Kandy were infuriated and went about in gangs attacking Hambaya shops and properties all along the railway line up to Colombo, shouting “Kolle Kolle” (Loot Loot). Soon, many parts of Colombo were engulfed in violence in which rowdies played a predominant part.

The police were nonplussed without a firm chain of command. Inspector General Herbert Dowbiggin was at sea. Police were issued rifles without ammunition. But things changed radically on June 2, when Governor Chalmers imposed Martial Law, with particularly draconian provisions. A free hand was given to the local cops and the 28 the. Punjabis, a British-officered, Muslim-majority Indian army unit then deployed in Ceylon to face a possible German attack during World War II (1914-18).

According to Ramanathan, Chalmers was persuaded to take extreme steps by some vested interests. Besides the tough commander of the army, Brig. Gen. HHL Malcolm, the others were a section of the traditional Sinhalese aristocracy who were “jealous” of the newly emerging Sinhalese bourgeoisie making a name for themselves and aspiring for leadership through the Temperance Movement.

Chalmers and Brig. Gen.Malcolm mistakenly viewed the spreading violence as a movement by the new bourgeoisie to overthrow the government with the help of Germans. Chalmers and Gen.Malcolm took no note of the fact that Whites or government properties were not attacked and that it was only a communal clash.

Charmers did not consult any knowledgeable Ceylonese, including his Maha Mudaliar, and his chief Ceylonese official, Solomon Dias Bandaranaike. According to Ramanathan, Chalmers, like his predecessor Sir Henry McCallum, felt that Ceylonese with a European style education need not be consulted as they themselves were alienated from their own people. They had forfeited the right to be consulted.

Many leading Ceylonese, including those who were manifestly loyal to the British, were imprisoned by Martial Law courts manned by the British officers of the 28 th.Punjabis. The well- known businessman and philanthropist Henry Pedris was executed only for firing in the air to scare away a mob trying to attack his shop in Colombo.

Hundreds of ordinary people were flogged or shot dead for the flimsiest of transgressions, on mere suspicion or on the complaint of rivals, Ramanathan says. Among the elite locked up in stinking cells for weeks was D.S.Senanayake, who later on led Ceylon to freedom. Heavy fines (in some cases in pounds sterling) were imposed on the wealthy. Heavy compensation was sought for arbitrarily assessed damages to property. British barrister Eardley Norton could not but remark that the Ceylon government was suffering from “treasonitis”. As an Englishman, he felt ashamed, Norton added.

An estimated 116 people were killed, including 63 in police firing; 4075 houses and boutiques were looted, 250 houses and boutiques were burned down, 17 mosques were burnt and 86 were damaged.

Though violence had ceased by June 6, Chalmers lifted Martial Law only on August 30. To save himself, he simultaneously issued an order indemnifying himself, Brig. Gen. Malcolm, and others for actions taken to suppress the rioting. But the Colonial Office in London disapproved of his actions and sent Sri John Anderson to replace him in 1916.

Buddhist and Pali Scholar

For all this, Sir Robert Chalmers an Oxonian, was an eminent scholar of Buddhism and Pali even as he was a high official in the British Treasury. He was agog when he was appointed Governor of Ceylon in 1913. The assignment in the Buddhist-majority Ceylon was right up his street. He was a favourite student of Prof.Thomas William Rhys Davids, the founder of the Pali Text Society in the UK.

Ceylonese Buddhists and political liberals were equally enthusiastic about Chalmers’ coming. They were in the midst of a politico-religious reawakening. The Temperance Movement had caught the imagination of the rising bourgeoisie. Liberal Ceylonese, cutting across communities, expected Chalmers, the Orientalist, to be more politically accommodative than his predecessor, Sir Henry McCallum, a tough military engineer.

According to Dr R.P.Fernando, historian of the British Raj in India and Ceylon, on joining the Pali Text Society in 1894, Chalmers published a paper in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (JRAS) entitled “The Madhura Sutta – concerning caste”. The sutta, which is contained in the Majjhima Nikaya, gives the Buddhist view on caste. The Majjhima Nikaya consists of 152 discourses by the Buddha and his chief disciples, which together constitute a comprehensive body of teaching concerning all aspects of the Buddha’s teachings.

In 1895, Chalmers published another paper in the JRAS entitled “Nativity of the Buddha” with the Pali text of an unpublished Sutta from the Majjhima Nikaya dealing with the ‘marvels and mysteries’ of the Buddha’s nativity. He then took over the task of translating the Jataka tales from Prof.Rhys Davids. The first volume of translations came out in 1895. According to Dr R.P. Fernando, this contained Jataka No.1 (Apannaka Jataka) to No.150 (Sanjiva Jataka).

Dr. Fernando further says that at the Paris Congress of 1897, Chalmers made a presentation on the Pali term Tathagata and published a paper on it in the JRAS in 1898. In this paper, Chalmers says that the first title assumed by the Buddha was not Samma-sambuddha but Tathagata. The Buddha used the same term in his dying words (Tamhehi kiccam atappam akkhataro Tathagata), Chalmers pointed out.

One of Chalmers’ first public engagements in Ceylon was to preside over the prize-giving at Vidyodaya Pirivena. The monks thought that he would not be able to pronounce Pali properly but he floored them with an extempore speech in chaste Pali.

However, Chalmers’ three-year tenure in Ceylon was marked by an issue in which he had neither an interest nor an inclination to apply his mind properly. This was the widespread rioting in 1915 involving Buddhists and Hambayas.

Though relieved of his post in Ceylon as a result of his clumsy handling of the riots in 1916, Chalmers remained unrepentant. He nonchalantly returned to his first love, Buddhist studies and Pali literature. As Master of Peterhouse College in Cambridge in 1924, he produced a metrical translation of the Sutta Nipata, the earliest teaching of the Buddha in Pali verse.

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...