There has been much hullabaloo over the proposed anti-terrorism law, which is widely thought to be part of a strategy to strengthen President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s position and help the SLPP-UNP administration keep its political opponents, trade unions and civil society organizations at bay. Thankfully, Justice Minister Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe has announced the deferment of the presentation of the proposed Anti-Terrorism Bill (ATB) to the parliament until the end of this month or early next month. The government seems to have got cold feet, at last, amidst fierce criticism of the controversial Bill.

The government sought to test the waters by making public the proposed law as an alternative to the existing PTA (Prevention of Terrorism Act), which has drawn heavy criticism from the Opposition, the media, human rights activists and other pro-democracy campaigners including the international community. The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) has also condemned it as draconian. The ATB lacks a clear definition of ‘terrorism’ and could therefore provide for the use of anti-terrorism laws against strikers and anti-government protesters as well. It contains some salutary features, but the general consensus is that its negatives far outweigh its positives. This has also been the position of the ICJ as well. The Bar Association of Sri Lanka is among the professional associations that have taken exception to the ATB and called upon the government to put off the presentation of the ATB to the parliament.

Ineffectual Opposition

All it takes for autocracy to rise is the ineffectuality of the mainstream Opposition. This, we saw during the governments of J. R. Jayewardene and R. Premadasa from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. It took about 17 years for the SLFP to recover from the massive electoral setback it suffered at the 1977 general election; the UNP reigned supreme with the members of the Bandaranaike family fighting among themselves, and preventing others from rising to party leadership. The SLFP had only eight seats at the time, and civic disabilities were imposed on its leader Sirimavo Bandaranaike. The TULF had 18 seats, and the Ceylon Workers’ Congress and an independent group one seat each. The UNP had a five-sixths majority in the parliament, having won 140 seats under the first-past-the-post system, and unsurprisingly President Jayewardene ruled like a dictator, and his immediate successor, Premadasa, did likewise, after securing 125 seats in the 225-member legislature under the Proportional Representation system in 1989. But the situation changed due to a split in the UNP in 1991 and the formation of the DUNF, which revitalized the Opposition, paving the way for the 1994 regime change.

Today, owing to a split in the ruling SLPP, the Opposition is much stronger than it was between 1977 and 1991. It was able to muster as many as 80 votes against the 2023 Budget in December 2022 while the government secured 123 votes with two MPs abstaining. The SLPP had more than 150 MPs on its side initially and the number went down to 134 at the vote, where Ranil Wickremesinghe was elected President by the parliament, last year. Curiously, the Opposition claims that the country is heading for a dictatorship although the government is losing ground both in and outside the parliament as evident from a decrease in the number of MPs supporting the SLPP-UNP administration, which is also wary of facing an election.

How come the government, which was cringing and cowering during the first six to seven months, last year, has been able to launch a counterattack and put the mainstream Opposition on the defensive although its popularity is on the wane? This situation has come about because the main Opposition party, the SJB, failed to provide proper leadership to the resentful public when they took to the streets last year, unable to bear crippling economic hardships and shortages of essentials. Leaderless protests erupted and were subsequently hijacked by the far left, which, however, could not harness public resentment to bring about a regime change although the protesters succeeded in forcing Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa and President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to resign. The unintended beneficiary of Aragalaya was Ranil Wickremesinghe, who became Prime Minister and President in quick succession. The SJB became a follower rather than a leader. The JVP gained more political mileage from the Aragalaya protests more than any other party, but failed to convince the public that it was pragmatic enough to be able to turn the economy around. It only kept demanding that reins of government be handed over to it, and blundered by trying to capture the parliament in July 2022, and thereby giving President Ranil Wickremesinghe an opportunity to launch a successful counterattacks and neutralize Aragalaya and infuse the public with some hope.

SJB’s dilemma

It is widely thought that the JVP has emerged stronger than the SJB politically, thanks to Aragalaya, so much so that its leaders have become the darlings of even some Colombo-based tycoons, who even host dinners for them. A few years ago, whoever would have thought the Colombo elite would receive JVP leaders with open arms? Probably, the business community is wooing the JVP by way of an insurance policy; although it does not have enough votes to form a government or even gain control of a municipal council, its trade union arm is strong and capable of causing trouble to business leaders.

The JVP rallies are well attended and its supporters are very active on social media. But the question is whether the JVP will be able to outperform the SJB electorally. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa failed because he lacked experience. The JVP is also not au fait with running a government. Some of its leaders only had brief stints in President Chandrika Kumaratunga’s Cabinet in 2004, and could not prove themselves. The SJB has an edge over the JVP in this respect, but it too has not been able to win public confidence. Its only strength has been the unpopularity of the government.

President Wickremesinghe is working overtime to recover lost ground on the political front with a view to running for President next year. The only way he can achieve this goal is by eating into the SJB’s support base, which formerly belonged to the UNP, and winning over the Opposition MPs. He has already engineered several crossovers, and the UNP propagandists are floating a story that a large number of SJB MPs have pledged their support to the President, and their crossover is only a matter of time. Despite the UNP’s propaganda claims to have the public believe that the SJB is losing ground, SLPP MP Jayaratne Herath attended the SJB’s parliamentary group meeting on March 20. He has switched his allegiance to the SJB to all intents and purposes, and does not want to defect for fear of being sacked by the SLPP and stripped of his parliamentary seat. Herath represents the Kurunegala District, which former President Mahinda Rajapaksa organizes for the SLPP!

SJB MP Champika Ranawaka has founded a new party, the United Republic Front (URF), which will be officially launched next month. There are already 86 registered political parties and the URF will be the 87th! Ranawaka is too ambitious to continue to play second fiddle to SJB leader Sajith Premadasa, and has apparently decided to chart a course. His goal may be to contest the next presidential election, and offer himself as an alternative to President Wickremesinghe, Premadasa and JVP Leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake, who is very likely to run for President again.

It is too early to say whether he will break ranks with the SJB or whether some SJB MPs will throw in their lot with him, but Ranawaka will pose a political challenge to Premadasa as well as the SJB.

Democracy threatened

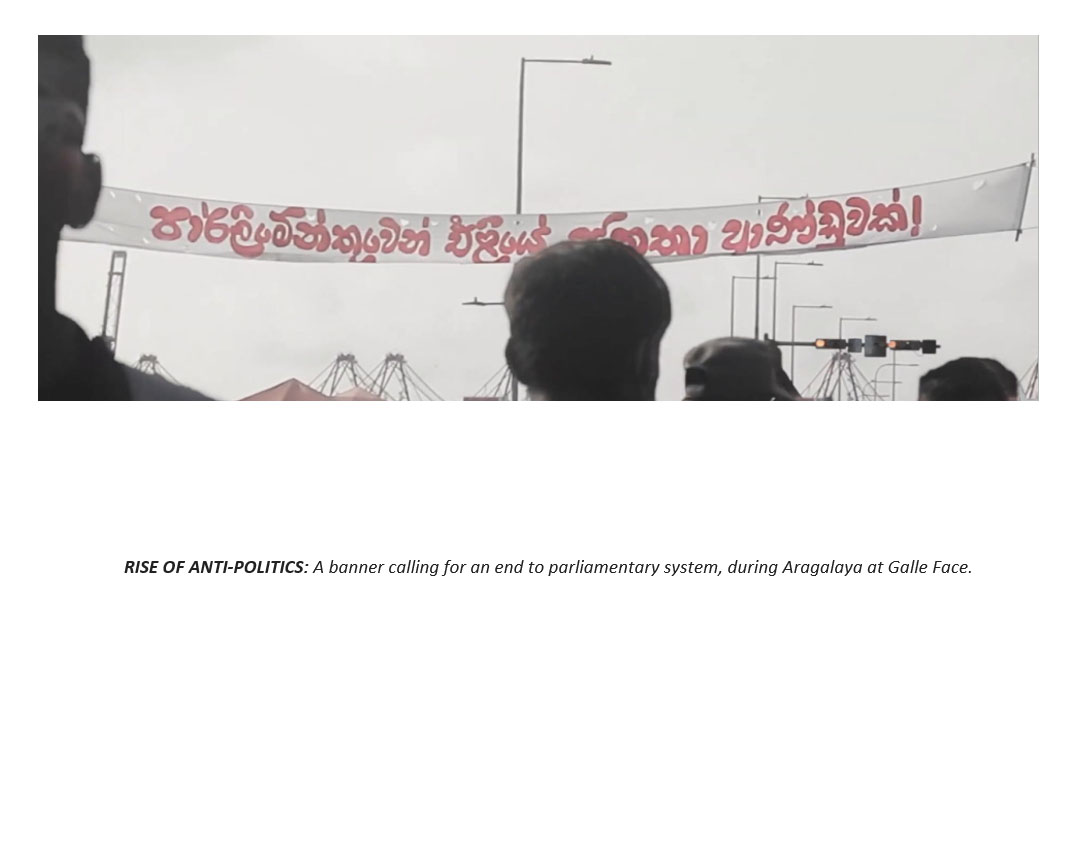

A government’s loss is the Opposition’s gain. This is what we saw in this country for decades. When a government loses votes, its main rival recovers lost ground and makes a comeback. But the situation has changed, today, with both the government and the mainstream Opposition failing to win over the public. This is not a healthy situation, for it could help extra-parliamentary forces advance their disruptive agendas, and throw the country into chaos, by means of leaderless uprisings. This phenomenon is called anti-politics, which is on the rise here, as could be seen from the disillusion of the youth with the mainstream political system and established parties.

It may be recalled that most Aragalaya activists called for the resignation of all 225 MPs, who represent the mainstream political parties. Unless the Opposition politicians stop fighting among themselves, get their act together and make a serious effort to live up to the expectations of the resentful public, anti-politics will receive a further boost; political stability and economic recovery will continue to elude the country.