There is said to be no such thing as a free lunch. Financial aid, foreign or otherwise, always comes with strings attached to it, and the recipients hardly have any choice, beggars are no choosers. These strings could be economic, political or even military, and they could even outweigh the benefits of the aid packages, in some cases. Nothing explains this geo-economic reality better than Sri Lanka’s current predicament.

The Rajapaksa-Wickremesinghe government finds itself in an unenviable position. Its political survival hinges on its ability to usher in economic recovery as fast as possible or at least a semblance of it, and this goal will remain unattainable unless it could enlist the backing of the world powers, which seek to advance their own agendas; they cannot be faulted for that. Why should they utilize their taxpayers’ money to help a country which has mismanaged its economy and declared itself bankrupt unless there is something for them in helping it? That is the name of the game.

As if the constricting IMF conditions such as the divestiture of state ventures, radical tax reforms, huge tariff increases, etc., were not enough, the government is now under pressure to implement the 13th Amendment to the Constitution fully, at the behest of India, which has not only agreed to restructure Sri Lanka’s debt, but also granted billions of dollars as bridge loans to prevent a humanitarian disaster here. India is swayed by its political compulsions, and has to be mindful of Tamil Nadu, which exerts considerable pressure on the centre in numerous ways. It is only natural that India, too, expects to further its interests economically and politically when it helps Sri Lanka.

Ranil bites off too much?

It is being argued in some quarters that President Ranil Wickremesinghe has bitten off more than he can chew by undertaking to implement the 13th Amendment fully, a task that all his predecessors chose to avoid for political and national security reasons. They stopped short of granting the Provincial Councils (PCs) land and police powers. Wickremesinghe’s decision to ensure the full implementation of the controversial 13th Amendment while struggling to save the economy has raised many an eyebrow.

But, in reality, President Wickremesinghe has not undertaken to devolve more powers to provinces of his own volition. He is under pressure from New Delhi to do so. He has only chosen to make a virtue of necessity because he is planning to contest the next presidential election and will have to secure the support of the Tamil political parties, which are demanding that more state powers be devolved to the provinces.

It was a UNP government that introduced the 13th Amendment and set up the PC, in the late 1980s, amidst protests and a spree of mindless violence that the JVP launched in a bid to abort the devolution project. Wickremesinghe is not a darling of the Sinhala nationalists, who do not vote for him anyway. The UNP’s base vote has hit rock bottom, and Wickremesinghe does not have to worry about the political consequences of the full implementation of the 13th Amendment. He only has to turn it to his advantage, if he could.

Presidential contest and Tamil vote

Perhaps, Wickremesinghe is apparently trying to emulate Maithripala Sirisena, who won the presidency in 2015, with the help of the UNP, the Tamil and Muslim political parties, civil society outfits and those who were fed up with the Rajapaksa administration.

Sirisena, however, was not seen as a person who appeased the LTTE or the Eelam lobby. During his presidential campaign, he marketed his brief stint as the Acting Defense Minister during President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s first term while the war was raging. At the same time, he made himself out to be a moderate Sinhala leader. Thus, he got the best of the both worlds with Wickremesinghe delivering the minority votes to him. But it is doubtful whether Wickremesinghe will be able to bag a sizable chunk of the Sinhala vote in a presidential contest. He will be able to do so only if the SLPP throws its weight behind him at a presidential election, but this is highly unlikely because the Rajapaksas are likely to field one of them as the next presidential election.

Political leaders and devolution

There are only a handful of political leaders whose policy towards devolution has been consistent, and they include former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, Wickremesinghe and the leaders of the traditional leftist parties.

Chandrika even offered to devolve power in excess of what is stipulated in 13th Amendment and set up Regional Councils with wider powers in her constitutional amendment package, which envisaged to abolish the executive presidency and restore the parliamentary system of government, in 2000. She claimed to have secured the backing of the UNP-led Opposition for her draft Constitution, but the UNP rejected it. Opening the debate on the draft Constitution, she did her utmost to secure the support of the Opposition, as she did not have a two-thirds majority in the House, but the UNP and the JVP literally set the constitutional Bill on fire in the House.

The reason the UNP gave for going back on its word was that President Kumaratunga had introduced some last-minute alterations to the Bill without their consent, and was trying to exercise the powers of both the President and the Prime Minister during the proposed transition period. Other opponents of the Bill campaign against the proposed Regional Councils, which they considered a halfway house between devolution and secession.

The following year, Kumaratunga’s SLFP-led People’s Alliance government fell due to mass crossovers including that of the then SLFP General Secretary S. B. Dissanayake. Wickremesinghe, who formed a government in 2001, continued with the process of finding a political solution to the war and entered into a ceasefire agreement with the LTTE, and was accused of compromising national security. After several rounds of peace talks, the LTTE asked for what it called an Interim Self-Governing Authority, and its demand effectively deadlocked the Norwegian-brokered peace process. President Kumaratunga sacked the UNP-led UNF government in 2004, citing national security reasons, and paved the way for the election of Mahinda Rajapaksa as the President the following year, albeit unwittingly.

MR blows hot and cold

Mahinda campaigned on a platform of nationalism, but carried forward the peace process under international pressure before retaliating to LTTE’s ceasefire violations militarily in 2006. His government presided over the decimation of the LTTE’s military muscle and the physical elimination of its leader Prabhakaran and other key Tigers. But he failed to manage the war victory.

President Rajapaksa was seen to be blowing hot and cold on devolution. He promised India what he termed 13A Plus, which was considered an offer to devolve power to the provinces in excess of what is already given. He may have done so to manage India during the war, but in doing so, he made a firm commitment, which India has not forgotten. Now, he cannot oppose Ranil’s offer in question.

Mahinda continued to be a Sinhala-Buddhist hardliner, and benefited from a massive block vote, which also stood his brother Gotabaya in good stead when the latter ran for President successfully in 2019. The Rajapaksa governments made it a point to celebrate the defeat of the LTTE on a grand scale annually so as to retain their appeal to the southern voters, and they bashed Wickremesinghe and the UNP quite a lot during their election campaigns in 2019 and 2020 for compromising national security.

Mahinda’s dilemma

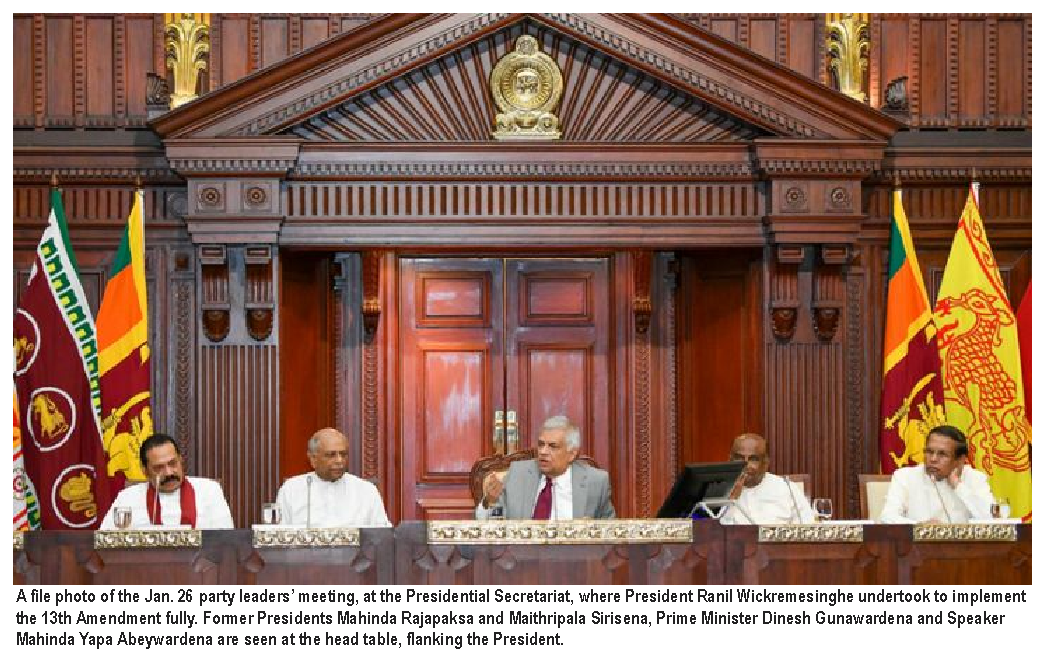

When President Wickremesinghe undertook to implement the 13th Amendment fully, while addressing a recent party leaders’ meeting, he was flanked by former President Rajapaksa and Prime Minister Dinesh Gunawardena, who is also opposed to anything that goes beyond what the PC have already got. Former President Sirisena was also at the head table.

Rajapaksa and Gunawardena cut very pathetic figures at that meeting, and they chose to remain silent, but their silence did not help them avoid embarrassment. They will have to make their positions known on President Wickremesinghe’s undertaking, and that will have a bearing on their vote banks in the run-up to the local government elections. The likes of SLPP MP Sarath Weerasekera have already registered their protest against the President’s offer. They are claiming that Wickremesinghe cannot go against the SLPP’s mandate. But what matters is the position of the Rajapaksa family on the issue.

The SLFP has not commented on President’s undertaking at issue, and it is not likely to oppose it vehemently, for Sirisena is now dependent on the government to prevent criminal proceedings from being instituted against him over the his lapses that led to the Easter Sunday tragedy.

Curiously, the JVP has sounded conciliatory; it has said the 13th Amendment is now part of the Constitution, and there is nothing wrong with its implementation although it will not help resolve the ethnic issue. It is accusing other political parties of arousing communal feelings by taking up the issue of devolution at this juncture. But having resorted to violence in the late 1980s in a bid to prevent the implementation of the 13th Amendment, it will have to explain why it has changed its position and decided against opposing President Wickremesinghe’s undertaking in question.

An attempt by President Wickremesinghe to implement the 13th Amendment fully is not likely to go unresisted; there are bound to be public protests, which will take their toll on the ongoing economic recovery programme. There’s the rub.