Pathfinder Foundation renews call for establishing a marine research station

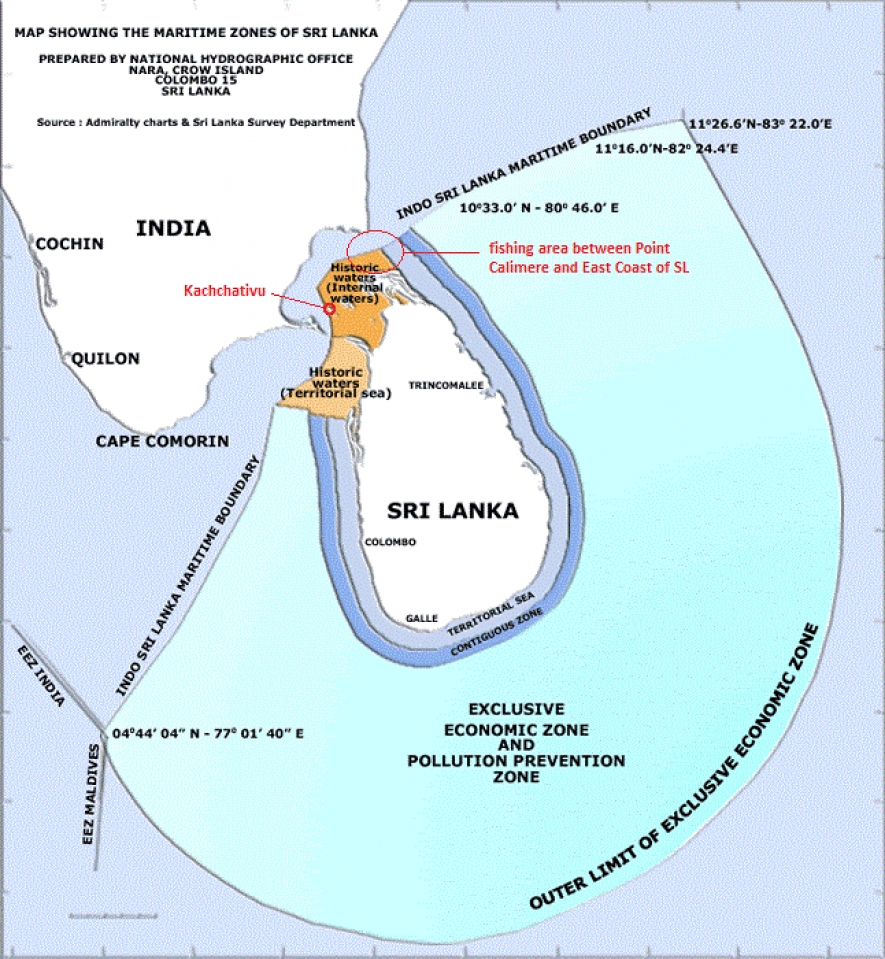

Now and then, Kachchativu island, lying halfway between the islands of Rameswaram (India) and Delft (Neduntheevu -Sri Lanka), has been hitting the news headlines. Mainly, such interests are evinced when several of the hundreds of Indian trawlers that cross the International Boundary Line (IMBL) three times a week and engage in bottom trawling in Sri Lankan waters get arrested for a variety of offences, including illegal entry into Sri Lankan waters, engaging in fishing without licenses and practising bottom trawling, which is an offence in Sri Lanka.

Compared with the regularity of these infractions, arrests are few and far between, and those arrested are released within weeks, if not days after court cases are completed in keeping with the country’s laws. Yet, egged by the fishing interests, Tamil Nadu politicians have made it a fine art to complain against arrests to New Delhi, demanding retrieval of Kachchativu, as if it would address the problem. While the eye of the storm remains on the island, the Indian public appears to be unaware that illegal fishing by Tamil Nadu fishermen covers a wide ark from Chilaw in the northwest of Sri Lanka to Mullaitivu in the east of the island, hundreds of kilometres away from Kachchativu. Nobody in India, either in New Delhi or Tamil Nadu, wishes to address the larger problem of illegal entry of Tamil Nadu fishermen into a foreign country, carrying out unlicensed fishing, and, in the process, damaging the fragile marine ecology by resorting to bottom trawling within Sri Lankan waters. Ironically, the Indian side, while demanding humanitarian treatment of its fishermen, seems to be oblivious to the denial of a decent livelihood to Sri Lankan fishermen in the north and the east of Sri Lanka, who are warned by their Indian counterparts not to venture into Sri Lankan waters three times a week, when they pillage their marine resources at will. Sri Lankan Tamil fishermen in the north and the east, being the real victims of the tragedy, ask in unison whether the continuation of this illegal practice for many decades is because New Delhi finds it easier to manipulate the Sri Lankan government than making Tamil Nadu fishermen comply with the bilateral and international agreements?

A new Indian RTI report on Kachchativu

The latest round of the controversy over Kachchativu started with a tweet by the Indian prime minister on March 31 referring to an RTI report provided to the BJP president of Tamil Nadu, which reportedly claimed that the Congress Party “callously gave away” the island of Kachchativu in 1974. Indian External Affairs minister followed up on the matter and said that when drawing the maritime boundary in June 1974, “Kachchativu was put on the Sri Lankan side.” Quoting relevant Articles of the agreement and a statement made by Minister of External Affairs Sardar Swaran Singh on July 23, 1974, he added that the exchange of letters between the two foreign secretaries on March 23, 1976, ensured that fishing vessels and fishermen of India and Sri Lanka would not engage in fishing in the historic waters, the territorial sea and the exclusive zones of the two countries without the express permission of the two countries.

He referred to continuous arrests of Indian fishermen and detention of their fishing vessels by Sri Lanka over the years, over which Chief Ministers of Tamil Nadu had repeatedly protested to New Delhi. It was evident that he was not making a case for reclaiming the island but striving to restore fishing rights “around the waters of Kachchativu.” To strengthen his case, he quoted the legal opinions of former Indian Attorney General M C Setalvad (1958) and the Legal Advisor of the External Affairs Ministry, Dr. K Rao (1960), citing customary rights for Indians to fish around Kachchativu. However, what was not figured in the interview was that thousands of Tamil Nadu trawlers cross the IMBL and engage in fishing over a wide arc from Chilaw in the West to Mullaitivu in the East, covering more than 450 kilometres of Sri Lankan coastline!

Even if Sri Lanka were to concede fishing rights around the Kachchativu island as demanded, how India would prevent the pillage of natural resources by Indian fishermen beyond the shores of Kachchativu of its economically debilitated neighbour covering a vast stretch of coastline was not made clear. It is noteworthy that at least for the last twenty-five years, India has been pressing Sri Lanka for licensed fishing in these waters to facilitate the majority of its 4000-strong trawler fleet to continue bottom trawling in Sri Lankan waters, ignoring the illegality of that practice according to Sri Lankan law.

It may be recalled that in June 2011, the TN government led by Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Jayalalithaa filed a petition in the Supreme Court of India seeking to declare the 1974 and 1976 agreements unconstitutional. However, the Indian government objected to the TN government’s arguments, stating that “No territory belonging to India was ceded, nor sovereignty relinquished, since the area was in dispute and had never been demarcated” and that the dispute on the status of the island was settled in 1974 by an agreement. Both countries considered historical evidence and legal aspects when arriving at the decision. The legality of the two agreements was confirmed in August 2014 by the Indian Attorney General Mukul Rohatgi, who represented the Centre. He told the Supreme Court bench led by Chief Justice of India R M Lodha, “If you want Kachchatheevu back, you will have to go to war to get it back.”

When a previous RTI report was made public in 2015, the Indian side adopted the same position in 2011, that the two agreements did not involve acquiring or ceding territory belonging to India since the area in question had never been demarcated. Against this backdrop, it is not a surprise that three highly respected former Indian High Commissioners of India in Sri Lanka, Shivshankar Menon Nirupama Rao and Ashok Kantha, two of whom later functioned as foreign secretaries, came out publicly against the latest Indian claim over Kachchativu.

Pathfinder is aware that elections in Tamil Nadu at the state or national level are occasions when the issue of Kachchativu receives undue prominence, as happened in March when a report under RTI was released to Tamil Nadu BJP President K Annamalai regarding the 1974 decision of the Indira Gandhi government to “hand over” the territory in the Palk Strait to Sri Lanka.

From a legal perspective, India did not “hand over” Kachchativu to Sri Lanka as claimed by the Indian side, simply because the island concerned was not a territory owned by India. Both countries claimed the island, and Sri Lanka established that historically, cartographically, and legally, the island had been administered by Sri Lanka since the Portuguese period, going back to 1615.

Indian claims to Kachchativu rebuffed during the colonial period

It has been recorded that even during the colonial period, India made claims over Kachchativu. It will be recalled that an Indian delegation visited Sri Lanka in October 1921 to discuss the fisheries line between the two countries. At the meeting, the Indian side made a vain attempt to establish the fisheries line one mile east of Kachchativu so that the island would be located within India’s waters. B. Horsburgh, the Principal Collector of Customs, who had also been the Government Agent of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka and therefore thoroughly knowledgeable on the subject, threatened not to proceed with the conference if the Madras officials led by C W E Cotton continued disputing Sri Lanka’s sovereignty over Kachchativu seeking to stake a claim over the island[1]. Eventually, both sides agreed to set the fisheries line three miles west of Kachchativu, thus bringing the island firmly under Sri Lanka’s control.

Pathfinder is aware that records confirm that even after the independence of the two countries, India used to seek the approval of Sri Lanka to use the island as a bombardment target. In response to a request made by Indian High Commissioner V. V. Giri in August 1949, his Sri Lankan counterpart Kanthiah Vaithianathan responded that the suggestion made by the Indian side to the effect that Kachchativu was situated outside the territorial limits of Ceylon was not correct and that “should the Royal Indian Navy desire to conduct fleet exercises as proposed, it will be necessary to obtain the permission of Ceylon Government to do so,” which response effectively ended the Indian request. Further, except for the claim made at the 1921 conference by the colonial officials of Madras, no other claim had been made by the Government of India until the mid-1950s. Therefore, it can be maintained that Sri Lanka’s sovereignty over the island was based on specific historical documentation, the consistent exercise of jurisdiction and physical control over the island.

The 1974 agreement was concluded after painstaking negotiations spanning the administrations of two Sri Lankan prime ministers, Dudley Senanayake (1965-1970) and Mrs. Sirima Bandaranaike (1970- 1977), during the tenure of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

It is clear that the RTI episode was election-related propaganda activity, and the Indian side had decided to use the opportunity to obtain approval for licensed fishing in Sri Lankan waters. Against this backdrop, Sri Lanka must prepare itself to respond to future pressures and pleas from the Indian side for licensed fishing.

Establish a fisheries research station on Kachchativu

Meanwhile, Sri Lankan authorities should know that they have been idling for exactly half a century after Colombo established its sovereignty over Kachchativu. The island may be a barren piece of real estate in the eyes of Sri Lankan authorities. However, it is a strategically located island that can be put to productive use, considering that its vicinity is famous for fisheries resources. Overfishing and damaging the sea bed due to continuous bottom trawling could destroy the area’s marine environment, depleting the fish stock, mussels, sea cucumbers, and other aquatic organisms that need to be protected. Sri Lanka is yet to understand how it lost its centuries-old lucrative pearl fisheries breeding grounds in Mannar, for which the island was known for many centuries. Against this backdrop, authorities concerned, including the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, the National Aquatic Resources Research & Development Agency (NARA), and other relevant institutions, should come up with ideas on how to use the island by establishing a permanent marine research station on the island, a proposal made by the Pathfinder Foundation way back in 2017[2].

Meanwhile, Indian authorities and opinion makers should bear in mind that the fly in the ointment affecting cordial India-Sri Lanka relations is not Kachchativu, an issue that was conclusively resolved half a century ago, but the relentless attacks on the fisheries resources in the northeastern sea by Indian trawlers. New Delhi should take proactive measures to address the decades-long issue and not expect the problem to disappear on its own or, eventually, expect Sri Lanka to accept the inevitable, which will come at a considerable economic and political cost to the state. This certainly is not how bilateral relations between India and its neighbours should be conducted, particularly during an enlightened era when Indian leaders do their utmost to stabilize its neighbourhood and see them developing along with resurgent India.

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...