Sri Lanka declared sovereignty over the Kachchativu Island in January 1977 under aproclamation signed by then President William Gopallawa.

The common belief however that India is ceded the disputed territory to Sri Lanka in 1976 largely because Indian perceptions had different dimensions especially those unique to the state of Tamil Nadu This belief triggered a string of legal suits in India’s Supreme Court. Many Sri Lankans haven’t had the opportunity to know the actual status of the negotiations behind the success story of declaring sovereignty over Kachchativu.

Former Sri Lankan Foreign Secretary W.T. Jayasinghe’s account of Katchatheevu has adequately dealt with the issue. The objective was to have a historical record for posterity. Hence, revisiting the negotiations that took place in the sixties and early seventies serves the purpose of keeping the people informed of the political history behind Kachchativu.

Acrimonious politics is akin to what has happened in Sri Lanka when regimes changed since independence and political parties promoted their political priorities. There have been two main parties at the helm of politics during the past 75 years. They reflected the feudal tendencies of the ruling class. There was also a lack of continuity in the projects underway when another party took over after a regime change.

Nevertheless, there was one occasion where there was continuity and which was in relation to resolving the Kachchativu issue. in governance. This may have been because of its external nature as many felt it may not have a direct bearing on local politics. In fact, the Kachchativu issue has had more effects in Tamil Nadu than in Sri Lanka. In the circumstances, for Sri Lanka to achieve legal rights over this disputed island, has been a political milestone on both the domestic and international fronts.

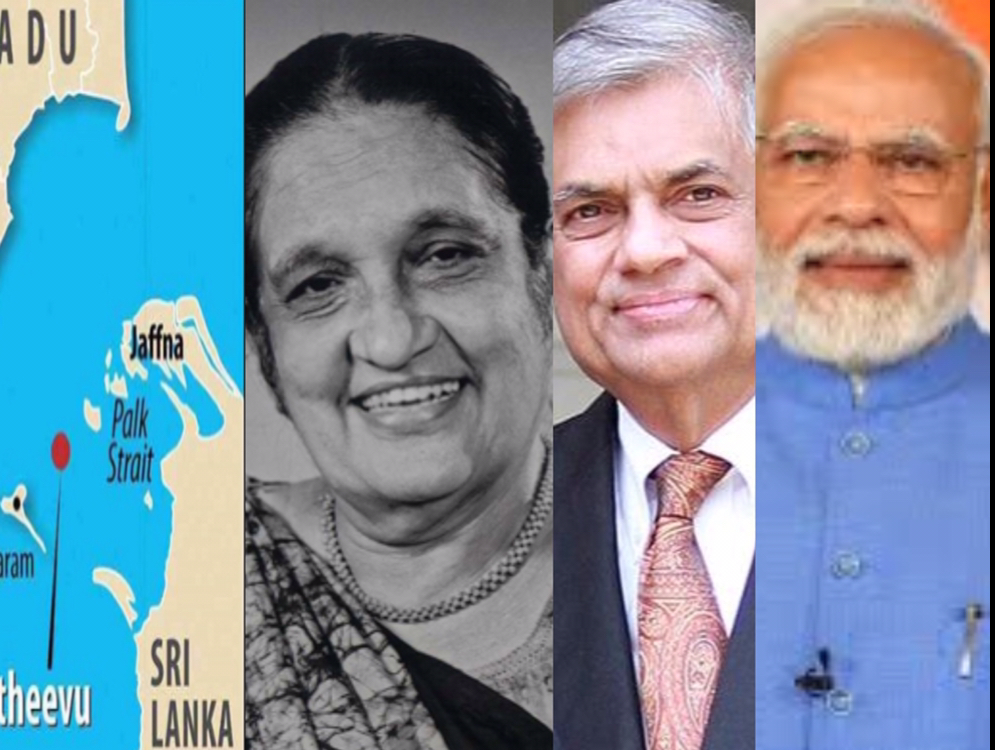

As Foreign Secretary W.T. Jayasinghe put it, this is an achievement accomplished through sheer hard work and diplomatic negotiations. He points out that such a significant achievement would not have been possible without the tireless efforts of two governments that took over the burden from their predecessors. Prime Ministers Dudley Senanayake and Sirmavo Bandaranaike had an equal share of responsibility to further the cause of Sri Lanka in front of tough Indian negotiators who made claims to Kachathivu.

Mrs. Bandaranaike continued from where Dudley Senanayake stopped, ensuring continuity in the way the issue was handled. It is a rare phenomenon in Sri Lankan politics. The negotiations did not strain bilateral relations in any way between Sri Lanka and India, and current politicians should learn from their predecessors’ achievements.

Kachchativu was no doubt a tender spot and has been an apple of discord between India and Sri Lanka for years. Despite the fact that it has been resolved, many do not know what the reality behind it is.

Sri Lanka proclaiming sovereignty over Katchatheevu, an island off the Rameswaram coast, is an achievement worth recognizing as a historical event in the annals of contemporary political history.

Nevertheless, foreign service officer and former secretary to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs W.T. Jayasinghe believes an achievement whichshould have been recorded in history has been buried in the sands of time.

In his introduction to his account of Kachchativu and Sri Lanka’s maritime boundaries, Secretary Jayasinghe states that “laws are not the only casualties in the middle of a war. Even a country’s achievements can be obscured by the perils of the moment during times of conflict and turmoil. One such achievement is Sri Lanka’s expansion of its coastal boundaries in the 1970s. This is when she resolved a claim that India had made on the island of Kachchtivu. She demarcated the maritime boundary between Sri Lanka and India and proclaimed her sovereignty over the maritime zones that are now recognized under international law.”

Secretary Jayasinghe’s perception was quite clear. Through this position he made an attempt to dispel the misconception that India had ceded or gifted Katchatheevu to Sri Lanka. This was despite good will or in the interests of India-Sri Lanka bilateral relations.

Instead, Tamil Nadu’s Chief Ministers, elected from time to time, held a view diametrically opposed to reality and the agreement reached on the ground.

The most recent one was by Chief Minister M.K. Stalin. He appealed to the Prime Minister of India to annex the disputed island as part of Indian territory, echoing the voice of former Chief Minister Jayalalitha. All the politicians who reach the higher echelons of Tamil Nadu politics have been confronted with this issue of sovereignty over Kachchativu many timesfollowing the Indo-Sri Lanka Maritime Agreement of 1974.

The objective of the Tamil Nadu politicians wasto secure the fishing rights of the fisher folk in their state. It makes sense for an Indian state with a densely populated coastal belt to entertain such ideas. It also allows the state to gain access to fishing rights in areas close to the southern tip of India.

What is vital in this context is the agreement signed between the two countries in affirmation.

The India–Sri Lanka maritime boundary agreements that were signed in 1974 and also 1976 between the two countries defined the international maritime boundary between the two countries. Treaties on maritime demarcation were necessary to facilitate law enforcement and resource management. In addition, they were necessary to avoid conflict in the Indian Ocean, particularly in the Palk Strait, since both countries are near one another.

The first agreement in 1974 was regarding the maritime boundary in waters between Adam’s Bridge and the Palk Strait.

The second agreement, signed on March 23 and which came into force on May 10, 1976, defined the maritime boundaries in the Gulf of Mannar and the Bay of Bengal.

In 1976, India, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives signed yet another agreement to determine the tri-junction point in the Gulf of Mannar. Later in November, India and Sri Lanka signed another agreement to extend the maritime boundary in the Gulf of Mannar.

During litigation in 2008, the Union government informed the Supreme Court of India that the question of the retrieval of Katchatheevu from Sri Lanka did not arise. This is because no territory belonging to India was ceded to Sri Lanka.

Considering the Center’s response to a writ petition filed by Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Jayalalitha seeking the retrieval of Katchatheevu from Sri Lanka, a bench of Justices B.S. Chauhan and S.A. Bobde posted the matter for a final hearing after three weeks to enable Ms. Jayalalithaa to file her rejoinder.

Ms Jayalalitha, who filed the petition in December 2008 as AIADMK general secretary, sought a declaration that the ceding of the islandby means of the 1974 and 1976 agreements between New Delhi and Colombo was unconstitutional.

Jayalalitha said the island was historically a part of Ramnad Raja’s zamindar, (the estate of the ruler of Ramnad or Ramanathapuram which is in Tamil Nadu) and later it became part of theMadras presidency. The island was always of strategic importance and of special significance for fishing operations in the area. She highlighted the suffering of fishermen from Tamil Nadu who inadvertently strayed onto the island. Because of the hostile attitude of the Sri Lankan navy, fishermen feared returning to fishing as they would be either killed or taken into custody if they entered Katchatheevu.

In or around 1921, Sri Lanka started claiming territorial rights over the island without any justification. Notwithstanding such claims, it continued to be a part of India.

The Union Government said the island was a matter of dispute between British India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and there was no agreed boundary. The contention relating to the status of this island was settled in 1974 by the agreement.

Both countries examined the question from all angles and considered historical evidence and legal aspects.

The position was substantiated by the 1976 agreement.

It said: “no territory belonging to India was ceded nor sovereignty relinquished since the area in question was in dispute and had never been demarcated.” Therefore, the contention of Ms. Jayalalitha that Katchatheevu was ceded to Sri Lanka was not correct and contrary to official records.

The Union government said that as per the two agreements, no fishing rights in Sri Lankan waters were bestowed on Indian fishermen. Under the agreement, “Indian fishermen and pilgrims will enjoy access to visit Kachchtivuand will not be required by Sri Lanka to obtain travel documents or visas for the purpose. The right of access is not to be understood to cover fishing rights around the island for Indian fishermen.”

Professor S.D. Muni, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, in an article written under the caption “Katchatheevu Settlement: Befriending Neighboring Regimes” in the renowned Economic and Political Weekly, states thus:

India’s leadership has a clear stake in stabilising and consolidating the existing distribution of power, political patterns, and strategies for socio-economic development in the South Asian region. Towards this goal, the Indian leadership is endeavoring to reach a consensus, together with its counterparts in South Asia, on the issues of peace, security, and stability. It is vital that it address these issues as well as those of its neighbours.

As a natural corollary, India’s leadership is keen to strengthen such governments in South Asia that would be amenable to its perception of the subcontinent. This is because they would be willing to work towards the evolution of the desired consensus. The removal of minor irritants like the Katchatheevu territorial dispute is part of the movement towards achieving this consensus.

As per the preceding excerpts from the article written by Professor Muni, the stand taken by the Union government in New Delhi is clear. This is because Kachchtivu Island has no dispute.

Secretary Jayasinghe has traced the historical aspects of the territorial waters of Sri Lanka from the time of the Portuguese and Dutch invasions. He presents historical evidence to support the claim that Sri Lanka has been a maritime hub since ancient times.

Katchatheevu came into the limelight in 1966, after Dudley Senanayake was elected for the fourth time as Prime Minister of Sri Lanka. TaFII (Task force on anti-Illicit Immigration) decided to extend its coverage to unauthorized immigrants during the Catholic Church festival in March.

Police personnel and sailors were deployed around the church to check on illegal immigrants from Sri Lanka.

A total of 150 people were arrested, and nearly 120 admitted they had come from KachchtivuIsland.

The arrest of such a large number of illegal immigrants was reported by the press both in Colombo and New Delhi.

On May 11, 1966, the Indian Express carried a statement from the Raja of Ramand. The Raja said the rights of the Raja of Ramand over Kachchtivu and other nearby islands have been recognized by the British under the “Isthimarar Sanad” treaty of permanent settlement.

On the 17th of May, several questions were raised in the Rajya Sabha regarding the political status of the island.

The Minister of State for External Affairs responded, saying that the political status of the island had not been resolved, that although the Raja of Ramand had zamindari rights over Katchatheevu these rights did not confer sovereignty. At a conference held in 1921, attended among others by representatives of the Madras government, it had been agreed that the Raja of Ramand’s zamindari rights would continue,

The state minister said, “we are friendly with Ceylon.” We will further strengthen this friendship. We will solve this problem in a friendly manner,” he said.

Kachchativu then became an issue of prime importance in Indo-Lanka relations. The issue was high on the prime minister’s agenda.

The Indian press was optimistic that Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake would help resolve the matter in a friendly manner.

The Indian Express carried an editorial on the issue on May 12, 1966, under the caption “Island dispute.”

Even though India’s claim is strong, it would be unwise not to recognise Ceylon’s difficulties. Ceylon is now strenuously fighting the menace of illicit immigration, and India has often cooperated with it. It is surely irksome that an island whose legal status has been vague should be allowed to become a base for illicit immigration. If the problem had arisen when Mrs. Bandaranaike was in power in Ceylon, it might have become serious. Mrs. Bandaranaike was under Chinese influence, and she was not as well disposed to India as Mr. Dudley Senanayake seems to be. The government of India should strive for an early settlement of the problem with the Senanayake government. This is because, with the return of the United National Party to power, relations between India and Ceylon have been cordial again. This island must not be allowed to poison it.

In Colombo, the Sun newspaper of the 16th of May reproduced the editorial in its entirety, highlighting that “if the problem of Katchatheevu had arisen when Mrs. Bandaranaike was in power in Ceylon, it might have become serious.”

Secretary Jayasinghe states that this characterisation of Mrs. Bandaranaike in the Indian press at this juncture as pro-Chinese and therefore less pro-Indian may have been a relic carried over from the part she played in helping to resolve the Sino-Indian conflict in 1962.

He also says the Maritime Transport Agreement that was concluded between Sri Lanka and the People’s Republic of China on July 25, 1963, regarding merchant shipping may also have been a contributing factor. Besides, Secretary Jayasinghe writes that the Indo-Lanka agreement signed on October 30, which was interpreted in some quarters as an attempt to compulsorily repatriate the Indian labour in the estate sector, was not favourably received in some parts of India, particularly after S.Thondaman, the President of the Ceylon Workers Congress, denounced the agreement in Tamil Nadu and New Delhi.

Questions in the Rajaya Sabah and a plethora of articles in the Indian press and Colombo acted as a wake-up call for the Dudley Senanayake government. Therefore, the Prime Minister decided that it was time to put an end to the Katchatheevu issue.

In the meantime, Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake, answering a question by the MP for Devinuwara, Ronnie de Mel, made a statement in parliament. He said that Ceylon’s position had always been that it had exercised firm control over Kachchtivu and that the government’s claim was well founded on historical facts.

Prime Minister Senanayake also believed that mere pronouncements may not suffice and that they had to take up the matter directly with the Indian government. He made this point clear to the then Secretary of the Ministry of Defence and External Affairs, G.V.P. Samarasinghe. The Prime Minister advised the officials to prepare the ground for discussions and negotiations and to compile a dossier outlining historical facts and Sri Lanka’s legitimate claim to sovereignty over Katchatheevu. Prime Minister Senanayake recalled how he assisted Mrs. Bandaranaike in talks with Nehru on the issue of immigrant labour on the estates in 1962.

As secretary Jayasinghe writes in his book, Dudley Senanayake was also involved in talks with Indian Prime Minister Nehru in London in 1953. These talks were held on the sidelines of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Although there seemed to be a breakthrough, the discussions could not proceed. Senanayake had no illusions about the matter, however, and he was determined to express his case on behalf of the country. He also said that the most significant thing that happened was the creation of a position for a legal advisor in the Ministry of Defence and External Affairs. This was followed by the appointment of C.W. Pinto to the newly created post.

T.B. M. Ekanayake, the senior Assistant Secretary to the ministry, and Pinto worked in tandem to locate records that would be relevant in establishing Sri Lanka’s case.

In their endeavour they were ably helped by the retired Government Archivist, SAW Mottau, who made a considerable contribution with historical evidence relating to Kachchtivu.

After an extensive search, Jaffna produced a six-page report by Mottau on the matter, which contained interesting facts about the historical evidence, including maps of the Dutch period.

The press also gave publicity to the research that was being carried out by the Ministry of Defence and External Affairs from time to timewhich created public interest in the matter.

Besides, a well-researched memorandum on “our claim for Katchatheevu ” was submitted in June 1966 by C. S. Navaratnam of Navaly Manipay, who was an acclaimed authority on the subject. Much of his research contributed to the final dossier on Sri Lanka’s claim. At the same time, Legal Advisor Pinto examined the records at the Public Office in London and at the India Office, where he was told that Indians were there before him. However, Pinto was able to unearth some valuable information on the delimitation exercise that was carried out in the 1920s.

Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake made a visit to India in November 1968 to reciprocate the visit of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to Sri Lanka in September 1967. High on his agenda during the discussion with Indira Gandhi was the issue of Kachchativu. The Prime Minister therefore asked Secretary G.V.P. Samarasinghe to have a note prepared setting out the possible course of action.

The Legal Advisor of the Ministry of Defence and External Affairs made the following observations on Kachchativu: he said that in his view, the issue of Kachchativuis essentially a legal dispute. He was of the view that it should be settled by the application of the rules of public international law. The suggestion he made was to refer the matter to the International Court of Justice. The example he cited was the dispute between the United Kingdom and France over some arid and sandy islands in the English Channel.

However, there were two problems associated with this: Ceylon had not accepted the general jurisdiction of the court, and India’s acceptance excluded disputes between it and any other Commonwealth country. Therefore, it required a special agreement, about which India may have had reservations. The other issue was whether India would agree to arbitration which was also not possible following the Kutch award where the tribunal held against India. There would have been inhibitions on the Indian side.

The best way out was through mediation and negotiation using good offices. Then came the issue of demarcating the territorial boundaries between India and Sri Lanka. India has extended its territorial waters to 12 nautical miles. However, it would not have affected Sri Lanka’s claims for Katchatheevu, since she had exercised jurisdiction over the island since 1665. India also thought it fit to stake its claims over Katchatheevu and made it a point to inform the Sri Lankan High Commissioner in New Delhi, Siri Perera, through the secretary of external affairs, T.N. Kaul. The informal meeting between them took place prior to the high-level talks between the two prime ministers.

At the meeting with High Commissioner Siri Perera, Foreign Secretary Kaul came up with three suggestions to settle the question. Acondominium between India and Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), partitioning the island into two equal parts where each country could exercise its jurisdiction over its part, or a working arrangement between two parties, putting aside for the present the question of sovereignty.

Assuming the magnitude of the issue may diminish with time, Kaul pointed out that the first two suggestions are of a permanent nature while the third would be temporary. Siri Perera said that Kachchativu has been Sri Lanka‘s territory, contrary to the views expressed by the Indian side, but he expressed reservations about the third suggestion, stating that if an economic issue arose, how could it be resolved?

Then Kaul mentioned the discovery of oil in the area and said that it could be jointly exploited, but Siri Perera said that he would inform the authorities in Colombo of the suggestions made. It appeared that India was not quite pleased with the Kutch award and was anxious to see that a third party did not get involved in the resolution of the Kachchativu issue.

The issue was discussed at the highest political level between Prime Ministers Indira Gandhi and Dudley Senanayake. The discussions ended inconclusively. However, Prime Minister Senanayake brought home the idea that there was no issue with India conceding Kachchativuto Sri Lanka, provided that Sri Lanka made some concessions to India on fishing rights.

Earlier, Sri Lanka presented the median line drawn in 1921, which put Kachchtivuwell on Sri Lanka’s side. The issue faced by Indira Gandhi was the fishing issue raised by the Madras government. If the demarcation lines were drawn, even grazing Kachchtivu, Mrs. Gandhi said that she could pursue the Madras government to accept the position. Prime Minister Senanayake also stated that he would face severe political issues if he surrendered Kachchativu to India. Though it was a contentious issue, the leaders agreed to examine the possibility of reaching an amicable settlement through discussion at the bureaucratic level since India was advocating for international arbitration on the issue.

During the talks between the two prime ministers, strong claims both by India and Sri Lanka were discussed, but Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake stood by the earlier claim that Kachchativu had been a part of Sri Lanka for centuries. The Indians feared that the demarcation of territorial waters would be amended if Kachathivu was taken as a base line.

The House of Parliament in Colombo and the Loksabbah also discussed the Kachathivu issue at length, but Dudley Senanayake refused to make any alterations to Sri Lanka’s claims. Nevertheless, Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake was optimistic that the matter would be resolved without much consternation since he had done most of the spade work on Sri Lanka’s claim along with his officials in the Ministry of External Affairs.

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...