There have appeared signs of trouble brewing in the SLPP-UNP government. The two parties got on like a house on fire for a couple of months following the appointment of UNP leader Ranil Wickremesinghe as Prime Minister, at the height of the Galle Face protest campaign; they became dependent on each other to such an extent that the SLPP even had Wickremesinghe elected President in the parliament in July. But today the spokespersons of the two parties are making statements that suggest that their relationship has soured.

SLPP General Secretary Sagara Kariyawasam said in a television interview a few weeks ago that the SLPP was in power despite the changes that had occurred at the helm of the government. It had a parliamentary majority and got Wickremesinghe elected President, he said. The SLPP seems to be worried that the UNP under President Wickremesinghe’s leadership might undermine and overshadow it and therefore it should assert itself. Kariyawasam’s claim went unchallenged; the UNP chose to take it for granted. After all, he has told the truth; the party that controls the parliament is more powerful than the President when the latter is not its leader. The President becomes really powerful only when he or she is able to control the legislature.

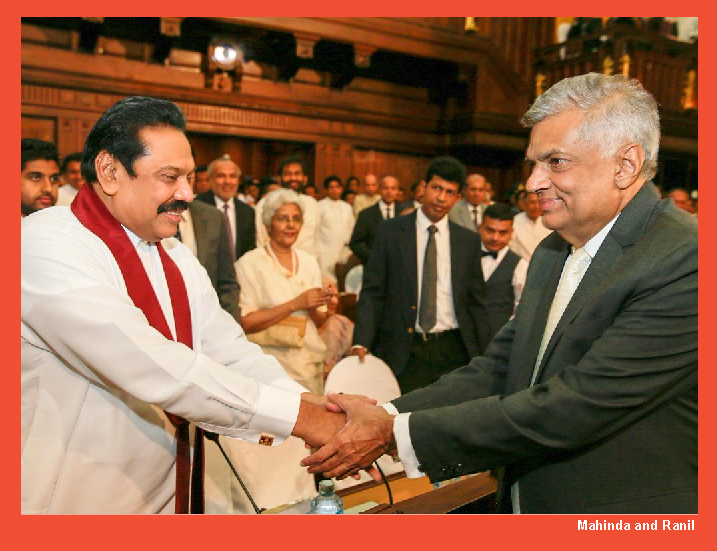

The UNP however has reacted to former President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s claim at an SLPP meeting in Kalutara, on 08 July, that Ranil was a different person today as they (meaning the Rajapaksas and the SLPP) had reformed him. UNP Spokesman Range Bandara lost no time in responding; he said it was Wickremesinghe who had reformed the SLPP! Namal Rajapaksa has sought to defend his father’s claim. He says Ranil has reformed and no longer acts according to the whims and fancies of western embassies, and has even got tough with protesters unlike Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Adversity makes strange bedfellows, as it is popularly said, but differences among them surface and sometimes even lead to clashes when they are lulled into a false sense of security, or realize that the threats which brought them together have blown over and they no longer have to depend on each other for political survival. Expediency too brings about unlikely partnerships, and those who come together tend to break ranks when they think it is more expedient for them to part ways. Such political marriages of convenience are not uncommon in politics. It is said that in politics there are no permanent friends or permanent enemies, and there are only permanent interests.

The alliance between the SLPP and the UNP is not likely to end anytime soon despite the ongoing cold war in the government and claims and counterclaims the SLPP and UNP politicians are making at each other’s expense. Their uneasy truce is likely to last until the next election; if the SLPP suffers a humiliating defeat, as expected, with the UNP improving its performance at least slightly, then the latter might consider partying company for expediency, the way the SLFP pulled out of the Yahapalana government after the 2018 local government elections.

Never in one’s wildest dreams would one have imagined that the UNP and the SLPP would come together to form a government, their policies being as different as chalk and cheese. Their alliance has caused them to subjugate their policies to political expediency.

On the economic front, President Wickremesinghe has had his own way, and the SLPP has fallen in line. His economic programme is similar in many respects to the Regaining Sri Lanka project of the UNP -led UNF government (2001-2004), of which he was the Prime Minister. UNP governments are characterized by divestiture programs, which the Rajapaksas have consistently campaigned against at last several elections. One can argue that the SLPP government had made a policy U-turn on privatization long before forming an alliance with the UNP; last year, it transferred 40% of the state-owned shares of the Kerawalapitiya Yugadanavi Power Plant to a US Company named New Fortress Energy; and this move is believed to be the first step towards ending the state monopoly on the power and energy sectors. It can also be argued that the government has agreed to the restructuring of state ventures under pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which requires countries to carry out structural adjustments to qualify for economic assistance. But the government under President Wickremesinghe’s presidency has become extremely overenthusiastic about the restructuring programme. It has undertaken to restructure the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) before the year end, and the Ceylon Electricity Board is also expected to go the same way sooner or later. The Petroleum Products (Special Provisions) Amendment Bill, which seeks to liberalize the petroleum sector, was passed by the parliament on Tuesday (18) amidst protests by the CPC trade unions, which launched a sick note campaign, crippling fuel distribution.

Attending a discussion on the Trincomalee District Development Plan, on Friday, President Wickremesinghe declared that Sri Lanka would not have faced a fuel crisis if the Trincomalee oil tank farm to India in keeping with an agreement the UNF government signed in 2003, when he was the Prime Minister. This shows how keen he is to divest state assets in keeping with the UNP’s core economic policies. He was not under any international pressure when he had the Hambantota Port leased out to the Chinese in 2017. He did so of his own volition, claiming that it was prudent to lease the port rather than pay back loans obtained for its construction.

There is hardly any difference between the SLPP and President Wickremesinghe or the UNP where their economic policies are concerned.

The Mahinda Rajapaksa administration (2005-2015) was widely considered pro-Chinese, and that was a main reason why the western powers turned hostile towards President Rajapaksa and welcomed the 2015 regime change. But the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government’s foreign policy lacked direction; Mahinda was seen to be pro-Chinese while Basil was considered pro-Indian. The latter was also accused of being partial to the US-led western bloc. Under the Wickremesinghe presidency, there has been a reorientation of the country’s foreign policy, and the government is seen to be currying favor with India and other QUAD (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue) members—the US, Japan and Australia.

The government’s policy towards the UNHRC, however, has not undergone any change. During the Yahapalana government (2015-2019), the then Prime Minister Wickremesinghe adopted a conciliatory approach towards the UNHRC and went so far as to cosponsor a resolution on Sri Lanka, but today he has chosen to go along with the confrontational policy adopted by the Rajapaksas. Nor have the US and its allies softened their stand on Sri Lanka in Geneva on account of Wickremesinghe being the President. In fact, the government has drawn heavy flak from Geneva for its handling of accountability issues, under Wickremesinghe’s presidency, and the UNHRC has encouraged ‘the international community to support Sri Lanka not only in its recovery but also in addressing the underlying causes of the crisis, including impunity for human rights violations and economic crimes’.

It may be seen that President Wickremesinghe and the Rajapaksas have compromised some of their policies in respect of foreign relations for the sake of their political cohabitation.

President Wickremesinghe has made a volte-face where national security is concerned. One of the main allegations that the SLPP used to level against him when he was the Prime Minister from 2001 to 2004 and again from 2015 to 2091 was that he was not well disposed towards the security forces and neglected national security. But today he has reposed trust in the military and is using the armed forces and the police to suppress anti-government protests. He has succeeded where former military officer turned President Gotabaya Rajapaksa failed.

The Presidential Commission of Inquiry, which probed the Easter Sunday terrorist attacks, has faulted Wickremesinghe, among others, for leniency towards extremists. Its final report says that ‘…. the lax approach of Mr. Wickremesinghe towards Islamic extremism as the Prime Minister was one of the primary reasons for the failure on the part of the then government to take proactive steps towards Island extremism’. This kind of criticism may have made President Wickremesinghe to depend more on the military and the police in dealing with troublemakers. The fact that the anti-government protesters torched his house despite his leniency towards them is said to be the main reason why he chose to get tough with them when he was appointed the Acting President after President Rajapaksa’s dramatic exit. But, overall, his policies in respect of security affairs have undergone a radical change and come to overlap with those of the SLPP, and this could be attributed to the influence of the Rajapaksas who earned notoriety for adopting militarized responses to almost all issues.

Thus, it may be seen that President Wickremesinghe has undergone a discerning change owing to his alliance with the SLPP although the Rajapaksas’ claim that they have reformed him is an overstatement of facts. It is equally true that the SLPP and the Rajapaksas have also compromised some of their policies owing to Wickremesinghe’s influence.

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...