By P.K.Balachandran

Colombo, December 30:

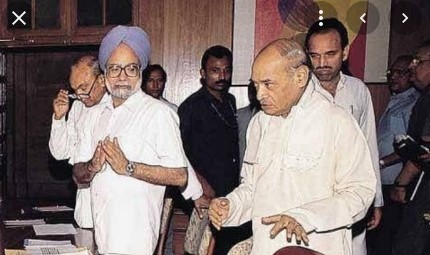

Dr.Manmohan Singh, Prime Minister of India from 2004 to 2014, who died in New Delhi last Thursday at the age of 92, was the answer to Prime Minister Narasimha Rao’s prayers for the redemption of the broken Indian economy in 1991.

And Dr.Singh, a believer in a liberalized economy, was at the right place at the right time, to bring about drastic changes in the Indian economy and also in the mind set of India’s political and capitalist classes, as desired by Premier Rao.

Singh had left an indelible mark on India’s economic history: first as Finance Minister in the Narasimha Rao government from 1991 to 1996 and subsequently as Prime Minister from 2004 t0 2014.

The soft-spoken Singh single-mindedly transformed a stagnant, stifled and wayward Indian economy into an effulgent and thriving one. Though there are yawning gaps, India’s liberalized economy is now giving millions a better and productive life and is making India an investment destination for the first time since independence in 1947.

While previous Indian Prime Ministers were dyed-in-the wool politicians, Singh was an Oxbridge educated economist, banker and a financial and economic bureaucrat. Narasimha Rao chose Singh to be his Finance Minister because his right wing views were in tune with Singh’s. In his doctoral dissertation submitted to Oxford University Singh had argued that trade would be an important factor in the development of a less developed country like India. The Indian scholar was opposed to the Statist Soviet model, popular among development economists at that time.

With Rao’s full backing and opposition leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s silent cooperation, Singh deregulated the Indian economy despite stiff opposition from his own Congress party, the trade unions and other who were benefiting from the entrenched State controlled system.

The Rao-Singh team, ably assisted by economists Montek Singh Ahluwalia and others, withstood the headwinds and set in motion a series of changes which could not be reversed by any government since then. In his first budget speech as Finance Minister in 1991, Singh said: “No power on Earth can stop an idea whose time has come.”

His reforms changed the private sector’s thinking. Attitudes to international trade changed. This led to higher rates of growth: to over 6 % between 1991 and 2004 and over 8.5% between 2003 and 2007. India became one of the fastest growing economies in the world after China. Radical reforms also brought more foreign investment into the country. When he left the Premiership in 2009-2010 forex reserves totalled US$ 600 billion. It was a mere US$ 1 billion when he became Finance minister in 1991.

Background

Independent India’s economic history had a major role in pushing the country to abandon Soviet-style Statistic policies, says Rahul Mukherji in his paper: The State, Economic Growth, and Development in India (Taylor and Francis Online).

India started off with a 2% GDP growth per annum, derisively described as the “Hindu rate of growth.” Till 1974, GDP grew between 3 to 4% per annum. Growth increased to over 5% between 1975 and 1990 when the private sector was given greater leeway under Rajiv Gandhi’s Premiership.

However, the peculiarities of India’s democracy were standing in the way of real reforms. Decisions were subject to pulls and pressures, and shaped by sectoral and socio-political lobbies. These led to short-sighted decisions. There was no way India could adopt the East Asian model of growth which rested on an autocratic, apolitical governance system, Mukherji says.

The 1980s (the Rajiv Gandhi era), saw faint signs of progress. Some industrial deregulations favouring the private sector occurred. Controls over expansion of enterprises were eased which enabled units to utilise economies of scale. Rajiv Gandhi corporatized parts of the Department of Telecommunications (DOT), despite vehement opposition from the bureaucracy.

Rajiv drew the more professional and modern Association of Indian Engineering Industry (AIEI) closer to the government. As a result, the hitherto influential members of the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) who were used to obtaining licenses by supplying the ruling party with funds, lost power.

This period of deregulation witnessed the emergence of software as a booming export oriented sector. Entrepreneurs were given greater choice in respect of imports; given easy finance for imports needed for exports. Government invested in software technology parks, which provided Indian firms with cheap connectivity, office space and infrastructure.

1990-91 Economic Crisis and Singh Era

Despite these changes for the better, India sunk into an economic crisis in 1900-91. It was forced to pledge its gold to secure a US$ 405 million loan from the Bank of England to navigate a balance of payments crisis, though the loan was quickly repaid. However, when Singh took over as Finance Minister in 1991, forex reserves were only US$ 1 billion, good for only two weeks of imports. According to Indian Express, between 1991 and 1993, India borrowed US$ 2.2 billion from the IMF under two standby arrangements, besides US$ 1.4 billion under the Compensatory Financing Facility in early 1991.

To revive the sagging Indian economy, Singh de-licensed industry allowing companies to produce without a license, whatever they liked in almost all areas. He devalued the Rupee making India’s software and other exports more competitive. A better exchange rate and improved products made Indian watches, motor bikes, cars and trucks more competitive than even their counterparts from Japan.

The entrepreneurial instincts of Indian businessmen were allowed to flower. Pharmaceuticals, gems and jewellery, and automotive parts emerged as leading sectors. The Tatas purchased the Tetley brand of tea for US$ 432 million, which made it the second largest producer of packaged tea after Unilever’s Lipton tea. Tata Steel won the title of the Best Steel Company in the World, accorded by World Steel Dynamics. Tata went on to acquire the Anglo Dutch Corus Steel for US$ 11 billion in 2007, in the fourth largest deal in the history of the industry. Mukherji points out.

Tariff liberalization reduced the prices of Indian finished products. Non-debt creating investments of multinational corporations were viewed favourably. Between 1991 and2002, India received US$ 48 billion in FDI. From being an IMF borrower in 1991-93, India emerged as a creditor to the IMF.

India’s stock markets were reformed, The National Stock Exchange (NSE) was set up which in turn led to the reform of the warped Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE).

Downside

However, liberalization did not turn out to be an unmixed blessing, Mukherji points out. The transformation was not holistic. Trade union laws increased the propensity of Indian industry to remain capital intensive, resulting in unemployment. The greater leeway given to the small scale sector to encourage its growth, hindered the expansion of units. The small did not have the incentive to become big and exploit the economies of scale and make technological improvements.

The agriculture sector, which accounted for 60% of the population of 1.2 billion, had grown only at a rate of 1.65% between 1996/97 and 2004/05. Agricultural subsidies were there, but only the rich and middle-income farmers could benefit from them. 80% of the marginal farmers did not have access to formal loans for example, Mukherji points out.

The Industrial Disputes Act protected less than 10% of India’s workforce. Indian firms could invest in any sector but still they needed a plethora of state and central government permissions. These regulations often became a source of rent-seeking and patronage rather than a speedy and judicious clearance of an investment proposal based on its merits, Mukherji observers.

The latest Human Development Report shows that infant mortality of the poorest 20% in India is higher than what is seen in Bangladesh and Pakistan. According to a widely quoted estimate, between 1993/94 and 1999/2000, the number of Indians living with less than a dollar a day came down from 36% to 26%, which meant that India had about 270 million absolutely poor people in 2000, a decade after reforms.

Singh’s reforms undoubtedly and immensely benefitted the rich and the middle class but only marginally improved the lot of the poor who survived on gratuitous handouts, euphemistically called “welfare schemes.” The direct transfer of cash to rural beneficiaries is hailed, but in the absence of adequate employment generation, such transfers do not amount to poverty alleviation in the real sense of the term.

END

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...